Amato, Joseph A., Rethinking Home: A Case for Writing Local History. (Berkeley, CA: U of California Press, 2002. ISBN 0-520-23293-3)

Bachelard, Gaston, The Poetics of Space. (Boston: Beacon Press, 1969. ISBN 0-8070-6439-4 pb)

Bachelard, Gaston, The Poetics of Reverie. (Boston: Beacon Press, 1969 ISBN 0-8070-6413-0)

Bogart, Barbara Allen, In Place: Stories of Landscape & Identity from the American West. Glendo WY: High Plains Press, 1995) ISBN 0-931271-27-4

Fiffer, Sharon Sloan and Fiffer, Steve, editors. Home: American Writers Remember Rooms of their Own. (NY: Random House, 1995. ISBN 0-679-44206--5)

Gallagher, Winifred. The Power of Place: How Our Surroundings Shape Our Thoughts, Emotions and Actions. (New York: HarperCollins, 1993. ISBN 0-06-097602-0 pb)

Goodrich, Charles. The Practice of Home: Biography of a House. (Guilford, Conn.: The Lyons Press, 2004. ISBN 1-59228-416-7)

Greene, Elaine. Thoughts of Home: Reflections on Families, Houses, and Homelands. (New York: Hearst Books, 1995. ISBN 0-688-16988-0 pb)

Hiss, Tony, The Experience of Place: A New Way of Looking At and Dealing with Our Radically Changing Cities and Countryside. (New York: Random House (Vintage Books), 1990. ISBN 0-679-73594-1)

Kemmis, Daniel. Community and the Politics of Place. (Norman, OK: U of Oklahoma Press, 1990. ISBN 0-8061-2227-7)

Nisbett, Richard E., The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently... and Why. (New York: Free Press, 2003. ISBN 0-7432-5535-6 pb)

Pearlman, Mickey, A Place Called Home: Twenty Writing Women Remember. (NY: St. Martins Press, 1996. ISBN 0-312-12793-6)

Pollan, Michael, A Place of My Own: The Education of an Amateur Builder. (NY: Random House, 1997. ISBN 0-679-41532-7)

Rybczynski, Witold, City Life: Urban Expectations in a New World. (New York: Scribner, 1995. ISBN 0-684-81302-5)

Tuan, Yi-Fu, Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values. (New York: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1974. ISBN 0-13-925230-4 pb)

Tuan, Yi-Fu, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1977. ISBN 0-8166-0884-9 pb)

I notice that sometimes when I mention a book, people assume I'm recommending it. But this is not always the case. I haven't even read all the books above. Some of them (Yi-Fu Tuan, Rybczynski, Bachelard, Kemmis) are highly respected and certainly OUGHT to be recommended, but for different reasons. Kemmis is a practical and humanistic politician considering human community. Bachelard is a French philosopher writing poetry as much as reality. Tuan is a pseudonym for a respected professor. But Elaine Green simply edits a series of House Beautiful columns by various folks. (Not that they aren't intriguing!)

Feel free to add your own choices to the comments.

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

POLAR DUST BUNNIES

It has been so cold here that I’ve resorted to heating the cat food in the microwave so they’ll eat it. (How warm? To the temperature of mouse blood!) I’ve been so hunched over to keep warm, that my shoulders ache. And that’s with an electric laprobe, two layers of fleece, and long underwear. This old house leaks little knife-edges of chill when the temp goes below zero. But today we’re up to eight above and headed for the twenties tomorrow.

That wasn’t the biggest problem: my internet provider had what they called an “issue” with “authentication” for several days. Since when did the cyber community begin to pick up psychotherapy talk? Anyway, I was left adrift for a while and had to resort to filing, which was a rather psychotherapeutic occupation in itself. What do I REALLY want to keep? Where are the boundaries? What is the core issue in this file? Why am I doing this anyway?

Self-publishing is going slowly. Some friends claim they are buying dozens of books -- not knowing that I can see at my Lulu website every sale made and so I know they’re fantasizing. But when I search my name or the title of the book it comes up everywhere. It’s on Amazon, Powell’s, etc. even as a “used” book. How can it be used? It’s Print On Demand -- unless someone bought copies to resell. But I’d know that -- I can account for every sale so far. Quarterly, one is supposed to be sent one’s profit and the third quarter check (Aug, Sept, Oct) was supposed to come in November so I’m sitting here like a little bird with its mouth open, beseeching for a worm. Tomorrow is the last day of November.

One childhood friend, who has not bought a book and does not read my blogs, and yet protests that she thinks I’m a fabulous writer and so on, became so angry -- when I boasted about getting a thousand hits a week on my main blog and expressed some worry about starting a literary career at 67 -- that she told me off. I think she wrote me off because she was afraid that I might write her off -- self-fulfilling prophesy. You can’t fire me -- I quit. So, if I DO have a literary career, how many friends will it cost me?

Indigo agrees to highlight self-published Canadians

JAMES ADAMS

From Wednesday's Globe and Mail

The Globe and Mail

Toronto — Canada's largest retail book chain, Indigo Books & Music, has agreed to carry a selection of books by self-published Canadian authors, provided those books are packaged by iUniverse, the Nebraska-based affiliate of U.S. super-retailer Barnes & Noble.

Participating authors will have to process their books through iUniverse's Premier Plus system which, for a $1,349 fee, gets a writer an editorial evaluation of his or her manuscript, custom cover and book design, a "marketing tool kit" and other services. Copies of the books will be published on an on-demand basis, with the author paying for the print run, the fee being based on a discount of the book's retail price.

There's a selection process for all titles and those chosen will be displayed in "high-traffic areas" of Chapters, Indigo and Coles stores "for at least 60 days -- longer if the book keeps selling."

This strikes me as a sort of hybrid (i.e. half-assed) approach to coping with the new technology/old venues. Lulu.com is much less expensive for just printing and listing ($100 for an ISBN and Amazon, et al) but if one took advantage of the adjunct offers for design, publicity, marketing kits, and so on, it would be pretty easy to spend that much. Probably the most expensive part of this would be the editorial evaluation, but how does one know whether it is worth anything? Back in 1961 I was stung by Famous Writers, which was all encouragement until one was signed up for an expensive course with an airtight contract -- then an instructor’s assault began that was pretty hard to withstand for a person just starting out. The idea was to install writer’s block so you didn’t send any more assignments -- just checks. It worked, well, “famously.” Until the law caught up with them.

The “best” part of the above Canadian arrangement is the display deal, if they actually carry through. The most insidious part is “the author paying for the print run.” Don’t have to do that at Lulu.com unless you’re going to buy a bunch of your own books and sell them from under your arm at a conference or something.

I predict a lot more blundering and experiments before we settle into a new pattern. The headache of it is that one must commit to strategy without knowing whether it will ever amount to anything more than... well, dust bunnies.

That wasn’t the biggest problem: my internet provider had what they called an “issue” with “authentication” for several days. Since when did the cyber community begin to pick up psychotherapy talk? Anyway, I was left adrift for a while and had to resort to filing, which was a rather psychotherapeutic occupation in itself. What do I REALLY want to keep? Where are the boundaries? What is the core issue in this file? Why am I doing this anyway?

Self-publishing is going slowly. Some friends claim they are buying dozens of books -- not knowing that I can see at my Lulu website every sale made and so I know they’re fantasizing. But when I search my name or the title of the book it comes up everywhere. It’s on Amazon, Powell’s, etc. even as a “used” book. How can it be used? It’s Print On Demand -- unless someone bought copies to resell. But I’d know that -- I can account for every sale so far. Quarterly, one is supposed to be sent one’s profit and the third quarter check (Aug, Sept, Oct) was supposed to come in November so I’m sitting here like a little bird with its mouth open, beseeching for a worm. Tomorrow is the last day of November.

One childhood friend, who has not bought a book and does not read my blogs, and yet protests that she thinks I’m a fabulous writer and so on, became so angry -- when I boasted about getting a thousand hits a week on my main blog and expressed some worry about starting a literary career at 67 -- that she told me off. I think she wrote me off because she was afraid that I might write her off -- self-fulfilling prophesy. You can’t fire me -- I quit. So, if I DO have a literary career, how many friends will it cost me?

Indigo agrees to highlight self-published Canadians

JAMES ADAMS

From Wednesday's Globe and Mail

The Globe and Mail

Toronto — Canada's largest retail book chain, Indigo Books & Music, has agreed to carry a selection of books by self-published Canadian authors, provided those books are packaged by iUniverse, the Nebraska-based affiliate of U.S. super-retailer Barnes & Noble.

Participating authors will have to process their books through iUniverse's Premier Plus system which, for a $1,349 fee, gets a writer an editorial evaluation of his or her manuscript, custom cover and book design, a "marketing tool kit" and other services. Copies of the books will be published on an on-demand basis, with the author paying for the print run, the fee being based on a discount of the book's retail price.

There's a selection process for all titles and those chosen will be displayed in "high-traffic areas" of Chapters, Indigo and Coles stores "for at least 60 days -- longer if the book keeps selling."

This strikes me as a sort of hybrid (i.e. half-assed) approach to coping with the new technology/old venues. Lulu.com is much less expensive for just printing and listing ($100 for an ISBN and Amazon, et al) but if one took advantage of the adjunct offers for design, publicity, marketing kits, and so on, it would be pretty easy to spend that much. Probably the most expensive part of this would be the editorial evaluation, but how does one know whether it is worth anything? Back in 1961 I was stung by Famous Writers, which was all encouragement until one was signed up for an expensive course with an airtight contract -- then an instructor’s assault began that was pretty hard to withstand for a person just starting out. The idea was to install writer’s block so you didn’t send any more assignments -- just checks. It worked, well, “famously.” Until the law caught up with them.

The “best” part of the above Canadian arrangement is the display deal, if they actually carry through. The most insidious part is “the author paying for the print run.” Don’t have to do that at Lulu.com unless you’re going to buy a bunch of your own books and sell them from under your arm at a conference or something.

I predict a lot more blundering and experiments before we settle into a new pattern. The headache of it is that one must commit to strategy without knowing whether it will ever amount to anything more than... well, dust bunnies.

Saturday, November 25, 2006

"Neanderthals, Bandits & Farmers"

When I was in seminary, Steve Beall was always trying to develop a “theology of pastoralism” from the Tom McGuane book, “The Bushwacked Piano.” I never really understood what he was up to, but I began my own topological theology from Tillich/Eliade to the effect that there is a “horizontal” dimension (the earthly), and a “vertical” dimension (to the other-worldly, whether heavenly or satanic). This is a spatial assignment suprisingly widespread in various religious systems, some of which actualize the symbolic by climbing down into a hole (or Kiva) or by hiking to the top of a prominence (on a vision quest).

Then I organized the rest around the “home” (center) and the “wilderness” (as far out as you can get). Of course, you can make metaphorical hay out of this all along. The center (axis mundi: turning point of the world) is always where you are -- narcissistic but true. What choice do you have? Generally I got a bit confused when I went to working out the meaning of pastures, gardens, fields, and so on.

So I was pleased with my most recent remainder investment, a book called “Neanderthals, Bandits and Farmers: How Agriculture Really Began” by Colin Tudge. It’s an endearing 5” by 7.5” hardback, 52 pp., the dust jacket split top from bottom: emerald on top, purple on bottom. Considering that I’ve been putting lots of time and effort into capturing the actual worlds of my prairie ancestors (some fields, a lot more wilderness than now) and have been reading about the reconsideration of neanderthals in terms of both the skull of a little girl and the genomic patterns of their protein, this little book is really more of a book “marker” for ideas.

Written in 1998, there are no really new ideas in it. It’s an essay in the purest sense, essaying to reconsider a lot of old ideas in the light of then-new research. Gradually, the idea dawns that converting from hunting (pax Paul Shepherd) to agriculture was not a simple matter of progress nor was it quite the curse depicted in the Bible when the people were driven out of Eden and beset by the Flood -- but nearly. Climate study was confirming that indeed there was a mighty and unprecedented flood, more than just the melting of the glaciers. In fact, a climate shift that melted the ice caps in a few decades, raised the ocean by many feet, drowned the easily cultivated lands of what is now Iraq, forcing them to reinvent agriculture in tougher places. It could happen again, and not just in New Orleans. (A recent competition for a vision of Manhattan in the future took into consideration the possibility of it looking like Venice.)

A parallel body of theory was that human beings, through overpopulation and clever technology (the atl-atl), killed off whole species of animals -- just as we are doing today. Between Cain and Abel, we have changed the Earth and we continue to do it -- though we wonder, like Paul in the New Testament, “Why do I do what I would not?” So this little booklet is worth pondering.

Tudge’s idea is that people went to agriculture gradually, in several ways and stages, an insight which I appreciate:

1. Horticulture (from the Latin hortus meaning garden): “growing food plants intensively, initially on an individual basis.” So, one of the ways one can find the ancient camps of the Blackfeet along the paths they followed is to look for clusters of plants they liked and evidently took along to put where they would be convenient. Sarvisberries, sweetgrass, tobacco. Years ago I read an account of someone walking through the South American jungle with a “medicine man,” who watched for certain herbs and flowers, stopping to dig them up and transfer them closer to the village where he lived.

Second category is “arable farming” which entails breaking the soil, removing all pre-existing plants, and planting something new. Seeds, potatoes. Storable foods in enough quantity to support a city, which spares some people from "sweaty faced" toil so they can think but enslaves the plowman and his ox.

Tudge’s third phase is pastoralism -- animal keeping but not in the nomadic way. Most people would put it first, not third, seeing it as “more primitive” somehow. Doesn’t it go: “hunting, herding, fencing?” But Tudge is after another new idea from research: the management of grazing animals through the use of fire to move them around and to renew the grass. Another Blackfeet skill.

In some ways Tudge is only summing small paradigm shifts (if there IS such a thing -- maybe I should just call it “reframing the evidence”) that have begun to add up to something far more momentuous and world-shifting: how we came to be us and how we must save ourselves. Quite a religious subject: “what must we do to be saved?”

His answer is shocking: We must be lazier. He points out that in hunting cultures, the hunters -- like lions, or horseback Blackfeet -- mostly sleep and groom. They can catch enough meat for pleasant enough lives for most of them: the quick, the clever and the community-based. The others die. But in an industrious, hustling, production-based society, there is enough to encourage more and more people who do less and less that isn't just busyness. The few must feed the many. (What is it now, 2% of the people are farmers?)

I won’t go farther. This is Thanksgiving weekend. Thank you, farmers.

Then I organized the rest around the “home” (center) and the “wilderness” (as far out as you can get). Of course, you can make metaphorical hay out of this all along. The center (axis mundi: turning point of the world) is always where you are -- narcissistic but true. What choice do you have? Generally I got a bit confused when I went to working out the meaning of pastures, gardens, fields, and so on.

So I was pleased with my most recent remainder investment, a book called “Neanderthals, Bandits and Farmers: How Agriculture Really Began” by Colin Tudge. It’s an endearing 5” by 7.5” hardback, 52 pp., the dust jacket split top from bottom: emerald on top, purple on bottom. Considering that I’ve been putting lots of time and effort into capturing the actual worlds of my prairie ancestors (some fields, a lot more wilderness than now) and have been reading about the reconsideration of neanderthals in terms of both the skull of a little girl and the genomic patterns of their protein, this little book is really more of a book “marker” for ideas.

Written in 1998, there are no really new ideas in it. It’s an essay in the purest sense, essaying to reconsider a lot of old ideas in the light of then-new research. Gradually, the idea dawns that converting from hunting (pax Paul Shepherd) to agriculture was not a simple matter of progress nor was it quite the curse depicted in the Bible when the people were driven out of Eden and beset by the Flood -- but nearly. Climate study was confirming that indeed there was a mighty and unprecedented flood, more than just the melting of the glaciers. In fact, a climate shift that melted the ice caps in a few decades, raised the ocean by many feet, drowned the easily cultivated lands of what is now Iraq, forcing them to reinvent agriculture in tougher places. It could happen again, and not just in New Orleans. (A recent competition for a vision of Manhattan in the future took into consideration the possibility of it looking like Venice.)

A parallel body of theory was that human beings, through overpopulation and clever technology (the atl-atl), killed off whole species of animals -- just as we are doing today. Between Cain and Abel, we have changed the Earth and we continue to do it -- though we wonder, like Paul in the New Testament, “Why do I do what I would not?” So this little booklet is worth pondering.

Tudge’s idea is that people went to agriculture gradually, in several ways and stages, an insight which I appreciate:

1. Horticulture (from the Latin hortus meaning garden): “growing food plants intensively, initially on an individual basis.” So, one of the ways one can find the ancient camps of the Blackfeet along the paths they followed is to look for clusters of plants they liked and evidently took along to put where they would be convenient. Sarvisberries, sweetgrass, tobacco. Years ago I read an account of someone walking through the South American jungle with a “medicine man,” who watched for certain herbs and flowers, stopping to dig them up and transfer them closer to the village where he lived.

Second category is “arable farming” which entails breaking the soil, removing all pre-existing plants, and planting something new. Seeds, potatoes. Storable foods in enough quantity to support a city, which spares some people from "sweaty faced" toil so they can think but enslaves the plowman and his ox.

Tudge’s third phase is pastoralism -- animal keeping but not in the nomadic way. Most people would put it first, not third, seeing it as “more primitive” somehow. Doesn’t it go: “hunting, herding, fencing?” But Tudge is after another new idea from research: the management of grazing animals through the use of fire to move them around and to renew the grass. Another Blackfeet skill.

In some ways Tudge is only summing small paradigm shifts (if there IS such a thing -- maybe I should just call it “reframing the evidence”) that have begun to add up to something far more momentuous and world-shifting: how we came to be us and how we must save ourselves. Quite a religious subject: “what must we do to be saved?”

His answer is shocking: We must be lazier. He points out that in hunting cultures, the hunters -- like lions, or horseback Blackfeet -- mostly sleep and groom. They can catch enough meat for pleasant enough lives for most of them: the quick, the clever and the community-based. The others die. But in an industrious, hustling, production-based society, there is enough to encourage more and more people who do less and less that isn't just busyness. The few must feed the many. (What is it now, 2% of the people are farmers?)

I won’t go farther. This is Thanksgiving weekend. Thank you, farmers.

Friday, November 24, 2006

SEVERE COLD

There are two kinds of little old ladies in Valier: the kind who dreads wind and the kind who dreads cold. (Of course, we all dread ice underfoot and the threat of broken hips.) Hardly anyone dislikes neither and many people of every age and gender dislike both. Personally, I don’t mind wind, but I’ve come to hate extreme cold. I’m not talkin’ zero -- I’m talkin’ SUBzero. The kind of cold that leaves white coin dots on your cheekbones and makes your fingers numb.

When I was young I hardly cared and zipped around with no jacket (for short distances) and bedroom slippers for sprints to the foundry or shop. (Of course, they were often Bob’s bedroom slippers, which his mother bought for him. Substantial wool objects with a zipper up the front and a hard sole.) Out to the woodpile, no prob. Rarely any gloves either. The Sixties were the era of the mini-skirt and a couple of the senior girls froze their thighs. No one could decide whether that was reckless, brave, or maybe (ahem) erotic. “Oh, let me rub your limbs, dear! Warm you up!”

My best winter footware in those days was felt liners inside four-buckle galoshes, which I never buckled because I liked to go clashing and jingling along through the deep snow we used to have in those days. Old-time Indian cowboys would stop me on the street and make me buckle up, lest I fall flat on my face when the buckles caught on each other. In those days they neither loved nor hated white people -- they just tried to take care of everyone.

Today it was zero when I got up at 6AM and the ground was bare. After I read the paper and went back to sleep, I re-woke at 9AM and knew by the light -- muted and matte white -- that there was snow. Now -- late afternoon -- the temp is up to ten above and the sky has cleared so that the light has changed again. Now it’s bright, striped gold and blue. Just now I went out to sweep my sidewalks -- in my slippers, no gloves. Not that cold if one keeps moving.

Everything is very still, so that even this very dry light snow is staying balanced on the twigs. It’s easy to swish the snow-dust off the sidewalk, which is cold enough these days that it stays dry. The only problem is where people have stepped, crushing the snow into a felty cake that wants to resist the bristles. Someone insists on walking down my sidewalk, no matter what state it’s in. There’s only one other residence -- Loretta next door -- and she goes in and out the alley, ignoring her sidewalk in front. The rest of the block is mostly the Baptist church which clears the walks for Sunday only.

Alongside the house, where I swept earlier, some of the dry snow has already sublimated, been absorbed into the even drier air. The humidity in the house, where I’ve been washing dishes and boiling things, is 30%. Our precipitation, which was far above normal early in the year, has fallen to “trace.” Doorknobs don’t sting with a static discharge because this is an old-fashioned house with rugs instead of carpets and no electrically propelled heat.

My furnace is under the floor and works by convection. It’s great to stand on, except that the “modern” grille over the top is fairly fragile and costs $400. The directions say not to install it in a doorway, but that’s exactly where it is, so traffic beats it up. I try to remember to leap over it and guests following me through the house take my example, so we look like sheep or goats, imitating the leader.

The thing I dread the most about the cold is not the cold itself -- thanks to fleece, down, and electric bedding, I can cope pretty well. It’s the money. The cost of natural gas, piped, is supposed to be less this year than last, but my heat bill is double or triple in winter. The gas company was released from regulation a few years ago which has turned out to be a HUGE mistake. An international corporation from Australia is trying to buy it at the moment. I’m sure they’re not looking for a nonprofit investment.

In another of those “help the poor and the old” gestures that only use those categories to subsidize international corporations, one can apply for help with heating costs. I’ve applied for three years straight and been turned down each time, even though the people in the office helped me with the application and assured me that I qualified. This year the application form is much longer and includes the demand that one permit access to all records: financial, medical, employment, assistance, and so on -- plus the entire year’s bank statements.

There is an assurance of confidentially. I’ve learned from bitter experience that nothing NOTHING on the county level is ever confidential. Or impartial. The demonstrations and scandal over Bob Scriver’s sale of his artifact collection was propelled by the “confidential” list of the values (a MILLION DOLLARS!!! CANUBELIEVEIT???) that the white local insurance businessman maliciously leaked to NA political opportunists. He thought it was funny to see Bob, the “Indian lover,” attacked like that.

The most profound cold comes in the night. The house begins to pop and creak. Both cats want under the covers and as close as they can get. Usually it has cleared and stars stab the blackness. Aurora Borealis may wave her veils, but who can stand out there to watch? Our porch lights are less alluring but more reassuring, although if it gets cold enough the lightbulb in my “jam jar” fixture explodes.

When it’s so cold, little old ladies can’t sleep and prowl from one window to another. They might read or turn the radio on low. I don’t need to worry about an electricity blackout shutting down my heat, but others do. The people with hot water heat are at most risk. Who might be out there in the cold? Is that a dog howling? When the county snowplows can be heard far away, grinding and scraping, it’s time to sleep. Now they’ll watch for trouble.

When I was young I hardly cared and zipped around with no jacket (for short distances) and bedroom slippers for sprints to the foundry or shop. (Of course, they were often Bob’s bedroom slippers, which his mother bought for him. Substantial wool objects with a zipper up the front and a hard sole.) Out to the woodpile, no prob. Rarely any gloves either. The Sixties were the era of the mini-skirt and a couple of the senior girls froze their thighs. No one could decide whether that was reckless, brave, or maybe (ahem) erotic. “Oh, let me rub your limbs, dear! Warm you up!”

My best winter footware in those days was felt liners inside four-buckle galoshes, which I never buckled because I liked to go clashing and jingling along through the deep snow we used to have in those days. Old-time Indian cowboys would stop me on the street and make me buckle up, lest I fall flat on my face when the buckles caught on each other. In those days they neither loved nor hated white people -- they just tried to take care of everyone.

Today it was zero when I got up at 6AM and the ground was bare. After I read the paper and went back to sleep, I re-woke at 9AM and knew by the light -- muted and matte white -- that there was snow. Now -- late afternoon -- the temp is up to ten above and the sky has cleared so that the light has changed again. Now it’s bright, striped gold and blue. Just now I went out to sweep my sidewalks -- in my slippers, no gloves. Not that cold if one keeps moving.

Everything is very still, so that even this very dry light snow is staying balanced on the twigs. It’s easy to swish the snow-dust off the sidewalk, which is cold enough these days that it stays dry. The only problem is where people have stepped, crushing the snow into a felty cake that wants to resist the bristles. Someone insists on walking down my sidewalk, no matter what state it’s in. There’s only one other residence -- Loretta next door -- and she goes in and out the alley, ignoring her sidewalk in front. The rest of the block is mostly the Baptist church which clears the walks for Sunday only.

Alongside the house, where I swept earlier, some of the dry snow has already sublimated, been absorbed into the even drier air. The humidity in the house, where I’ve been washing dishes and boiling things, is 30%. Our precipitation, which was far above normal early in the year, has fallen to “trace.” Doorknobs don’t sting with a static discharge because this is an old-fashioned house with rugs instead of carpets and no electrically propelled heat.

My furnace is under the floor and works by convection. It’s great to stand on, except that the “modern” grille over the top is fairly fragile and costs $400. The directions say not to install it in a doorway, but that’s exactly where it is, so traffic beats it up. I try to remember to leap over it and guests following me through the house take my example, so we look like sheep or goats, imitating the leader.

The thing I dread the most about the cold is not the cold itself -- thanks to fleece, down, and electric bedding, I can cope pretty well. It’s the money. The cost of natural gas, piped, is supposed to be less this year than last, but my heat bill is double or triple in winter. The gas company was released from regulation a few years ago which has turned out to be a HUGE mistake. An international corporation from Australia is trying to buy it at the moment. I’m sure they’re not looking for a nonprofit investment.

In another of those “help the poor and the old” gestures that only use those categories to subsidize international corporations, one can apply for help with heating costs. I’ve applied for three years straight and been turned down each time, even though the people in the office helped me with the application and assured me that I qualified. This year the application form is much longer and includes the demand that one permit access to all records: financial, medical, employment, assistance, and so on -- plus the entire year’s bank statements.

There is an assurance of confidentially. I’ve learned from bitter experience that nothing NOTHING on the county level is ever confidential. Or impartial. The demonstrations and scandal over Bob Scriver’s sale of his artifact collection was propelled by the “confidential” list of the values (a MILLION DOLLARS!!! CANUBELIEVEIT???) that the white local insurance businessman maliciously leaked to NA political opportunists. He thought it was funny to see Bob, the “Indian lover,” attacked like that.

The most profound cold comes in the night. The house begins to pop and creak. Both cats want under the covers and as close as they can get. Usually it has cleared and stars stab the blackness. Aurora Borealis may wave her veils, but who can stand out there to watch? Our porch lights are less alluring but more reassuring, although if it gets cold enough the lightbulb in my “jam jar” fixture explodes.

When it’s so cold, little old ladies can’t sleep and prowl from one window to another. They might read or turn the radio on low. I don’t need to worry about an electricity blackout shutting down my heat, but others do. The people with hot water heat are at most risk. Who might be out there in the cold? Is that a dog howling? When the county snowplows can be heard far away, grinding and scraping, it’s time to sleep. Now they’ll watch for trouble.

Thursday, November 23, 2006

BRANDON, MANITOBA

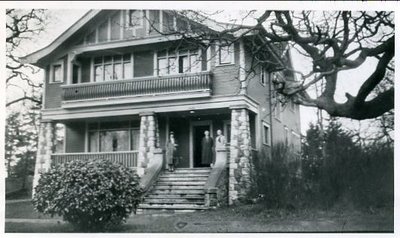

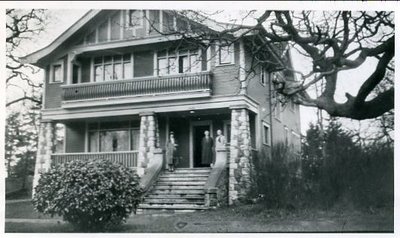

Thanks to the Kovar machinery, the Sam Strachans were at their most prosperous and optimistic point. Then came a 25% tariff on the machinery and the decision to move to Oregon. In the meantime, the Brandon house with the Kovar warehouse behind it was as comfortable as they had ever been. The address was 724 10th Street. There was a “sacred fireplace” that became the new anchor point for ceremonial photographs, and even a “sacred staircase.” The house would be an excellent location for several graduations and a double wedding as the children reached maturity.

Seth and Glenn were formally posed in fall, 1927, just before they left for “flying school” in Marshall, Missouri, in preparation for the acquisition of a small airplane for Kovar business. Seth began his lifework as a pilot in this way.

May is posed in her graduation splendor in June, 1928, dressed almost like a bride with a bouquet on her arm. (She earned a Certificate in Domestic Science from Manitoba Agricultural College.) In those days the fashion was white stockings with white satin shoes -- just as in the Seventies the fashion was black stockings with black patent leather shoes. The fireplace itself appears to be of glazed brick with a fancy enameled grill over the opening, probably intended for coal rather than wood. It seems quite English to my eye. The area above the mantel shows a built-in mirror. Two candlesticks adorn the actual mantel -- at least one can’t see the mantel clock. Maybe it stayed with its bookcase from the previous houses or maybe it just doesn’t show. There is an elaborate columned carpentry surround framing the whole fireplace area. The chair in both photos seems to be an unremarkable wooden chair, borrowed from someplace else. Other photos show the hearth as rubble! Broken rocks and possibly brick. This suggests that the original hearth -- marble? -- was removed for some reason and the pieces were a stopgap.

The stairway is very nice: carved wood, gracefully designed. A radiator shows, meaning that this house has a furnace or boiler which probably means a basement. This, along with a lack of easy chairs for reading near the fire, might suggest that the fireplace wasn’t really used for heat. This would be an excellent stairway for a bride to descend -- or two brides since the Strachan wedding was double. (Unusually good-looking couples, I might add! The brides dressed as May did for graduation except for veils gathered into little upside-down sugar bowls on top of their heads.) I suspect that the frieze at the top of the wall and the window shade were left by the former owner. Also the quite remarkable art nouveau wallpaper in the main room! I wish I knew the colors. I'm guessing turquoise, plum, orange!

The family was quite proud of the fact that this house had belonged to Martha Ostensko, the author of “Wild Geese,” published in 1925 and a great hit. Slyly dedicated to her father, the story is about a prairie patriach in territory more like Minitonas, who in his drive to succeed ruled his family too harshly. There is a terrible prairie fire arising from Caleb’s greed. The passage below comes late in the book after the fire. Lind is the school teacher who boards with the family.

“The first hoar frost came, and Lind woke one morning to find the earth covered with white, powdered glass. The sun took its glitter within a few minutes, but the land was not the same after it had gone. It seemed to have left a shadow over the stubble and over the short brown grass of the pastures to the west, and over the black corpses of the trees that had been ravished by the fire. The days that followed were as full of mellow radiance as those that had gone before, the wind was as soft and the sky as intimate a blue, but there was some change in the mood of the earth.

“Then Lind heard the honking of the first wild goose, high overhead. On a night that was cold with moonlight she heard it, a full, clear trumpeting, in a sky that was vacant of clouds. The wild geese were passing over -- passing over the haunts of man in their remote seeking toward the swamps of the south. They marked the beginning and the end of the period of growth. Next year they would fill the sky with their cold, lonely clamor at sowing time, and again when the earth would have closed in upon itself after yielding its growth.”

In 1996 a movie called “After the Harvest” was made for Canadian television, based on this novel.

Sam Shepard played the patriarch, but he was nothing like Sam Strachan, nor were his children like the trapped siblings in the story. Still, especially in Brandon, there was a sense of them trying their wings, looking to the south. Probably the exception was Elsie, who grew up in Brandon. When she married Glenn, she may have felt that the future of the family would be securely and prosperously in Brandon. In fact, she became a poet and would eventually have her work published in The Saturday Evening Post and Arizona Highways. Most of her adult life would be in Southern California, but she had no inkling of that yet.

Murdock McLean, called “Doc,” met the Strachan sons in Winnipeg at MAC and then their sister May. After a year back home in Reston, Ontario, on his father’s substantial farm -- big house with stone foundation, even bigger and always expanding barn, and a family to match with a patriarch a bit more like Caleb -- he decided to throw in with the Strachans in Brandon. He and May, along with Glenn and Elsie, formed a foursome. In old age, the two widows called each other late at night when rates were low to share their lives and memories, still close as school girls.

In fall of 1929 Bruce, graduated in Winnipeg, left for Oregon State College to get an advanced degree in “scientific agriculture.” Sam and Beulah, facing the economic future of Kovar, bought a house in Portland. May and Doc soon joined them. Glenn and Elsie stayed in Brandon in hopes that Kovar would somehow recover or at least survive. Elsie ran a little beauty parlor in an upstairs bedroom.

You know what happened next: economic depression like a prairie fire: so harsh and widespread that people across the continent died of starvation and suicide. Sam went up to Brandon to help close out the business and move the remains to Portland.

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

HUMANIACS AS TERRORISTS

House Passes 'Terrorism' Act Against Animal Activists

by Megan Tady

© 2006 The NewStandard

Wednesday, November 15, 2006 -- Monday afternoon, the US House of Representatives passed a bill that reclassifies unlawful animal-rights tactics as terrorism under certain conditions, even if they are non-violent.... the bill will classify civil disobedience actions -- such as blockades, property destruction, trespassing, and the freeing of captive animals -- as terrorism... enhance penalties against activists who "interfere" with animal enterprises by destroying property or engaging in behavior that appears "threatening." It even includes perceived threats to companies that work with animal enterprises and takes into account resulting profit losses.”

In other words, Oprah as terrorist. No more civil trials -- straight to criminal law. Not just “spitting on the sidewalk” but hard-core, locked-up-in-Guantanomo terrorism. It was easy to see this one coming.

There are several elements to this development. One is the meat industry, which wants no attention to its de-beaked chickens crammed into gym-baskets, it’s e-coli-spreading slaughter practices and feedlots, its illegal employees scalded and slashed by lousy work conditions, and so on. Another is the high-minded medical research community and its specially bred and expensive white mice and rats with “knockout” genetics, monkeys confined and infected because that’s the only way to find out about human diseases if they won’t let you do such things to humans, or cats literally wired for sex and violence in the name of understanding those potent human forces. The fur industry -- of course. So far growing plants are not included as victims of cruelty, but that food industry is also intent on eliminating public interference with its more dubious practices like not providing latrines for workers in the fields.

In short, 9/ll worked so well as a political ploy for Bush, was such an argument for power and secrecy, that entire industries have decided to follow suit. In the past when attempts have been made to regulate such organizations, they have depended on simple passive resistance: making things unavailable, stonewalling, conforming to the law only when inspectors were present, blocking the funding of enough inspectors to enforce the regulations. It’s all worked pretty well, a kind of board game of approach and avoidance.

But this is different. There is a edge in this approach, a determination to skewer the individual, to intimidate anyone who tries to take on the status quo by punishing him or her as “other.” At the very least, ecoterrorists will need a lot of money for lawyers. At the most they may simply disappear into “rendition,” confinement in a country with low standards about torture and no habeas corpus.

True enough that setting fire to laboratories, liberating mink from “ranches,” setting loose millions of dollars of mice and destroying the experiments they support, are bad things to do and often come from people who are neither thoughtful nor helpful. They meant to be provocative and look what they provoked! But defining them as “terrorists” ups the ante enough to attract the truly nutso. Do we want people blowing themselves up in local animal shelters?

In the last wave of extravagant superrich industries, the 1900’s Age of Gold, which many writers are beginning to compare to right now in terms of growing wealth disparity, there was violence against workers, sabotage against factories, riots and assassinations enough to dislocate public order. Is this what we’re moving towards?

Many humane workers think that they’re trying to make everyone be gentle pacifists who never kill any animals anywhere. They never consider overgrazing, belligerent deer in towns, vicious animals, or anything else that interferes with their vision of life as naturally an Eden: a zipless, prelubricated, eternal childhood Land of Sunshine. Instead, their harassment of government and corporate bodies has irritated the latter enough for this kind of out-of- proportion overkill.

I understand the irritation. When I was doing animal control, there were always individuals who locked onto us as evil monsters, used sunshine laws to demand time-consuming and expensive compilations of records, got on talk shows to whip up emotion over incomplete versions of lamentable cases, and generally hounded us into plugging our ears. But they weren’t terrorists. And a few of them had good sense -- they could become valued allies and friends. Still, there was always a rough edge of law enforcement that muttered, “Those women need a good ...” you know. Only a short step from there to rape, which can hardly be separated from violent assault. If they’re “only” terrorists...

No newspaper has discussed this federal law. I see no articles in magazines about it. Journalism believes that animal stuff is for children. All that tiresome stuff -- so hard to sort out. So...well, icky.

They tell me -- and I guess I believe it -- that in France there is no law against cruelty on grounds of being inhumane. Rather it is illegal to offend the sensibilities of others through cruelty. In this country, we don’t care much about sensibilities. The great overriding consideration is the profit margin. It is increasingly illegal -- to the point of being considered terrorism -- to interfere with anyone’s profit margin. Crimes against the dollar are crimes against the State.

by Megan Tady

© 2006 The NewStandard

Wednesday, November 15, 2006 -- Monday afternoon, the US House of Representatives passed a bill that reclassifies unlawful animal-rights tactics as terrorism under certain conditions, even if they are non-violent.... the bill will classify civil disobedience actions -- such as blockades, property destruction, trespassing, and the freeing of captive animals -- as terrorism... enhance penalties against activists who "interfere" with animal enterprises by destroying property or engaging in behavior that appears "threatening." It even includes perceived threats to companies that work with animal enterprises and takes into account resulting profit losses.”

In other words, Oprah as terrorist. No more civil trials -- straight to criminal law. Not just “spitting on the sidewalk” but hard-core, locked-up-in-Guantanomo terrorism. It was easy to see this one coming.

There are several elements to this development. One is the meat industry, which wants no attention to its de-beaked chickens crammed into gym-baskets, it’s e-coli-spreading slaughter practices and feedlots, its illegal employees scalded and slashed by lousy work conditions, and so on. Another is the high-minded medical research community and its specially bred and expensive white mice and rats with “knockout” genetics, monkeys confined and infected because that’s the only way to find out about human diseases if they won’t let you do such things to humans, or cats literally wired for sex and violence in the name of understanding those potent human forces. The fur industry -- of course. So far growing plants are not included as victims of cruelty, but that food industry is also intent on eliminating public interference with its more dubious practices like not providing latrines for workers in the fields.

In short, 9/ll worked so well as a political ploy for Bush, was such an argument for power and secrecy, that entire industries have decided to follow suit. In the past when attempts have been made to regulate such organizations, they have depended on simple passive resistance: making things unavailable, stonewalling, conforming to the law only when inspectors were present, blocking the funding of enough inspectors to enforce the regulations. It’s all worked pretty well, a kind of board game of approach and avoidance.

But this is different. There is a edge in this approach, a determination to skewer the individual, to intimidate anyone who tries to take on the status quo by punishing him or her as “other.” At the very least, ecoterrorists will need a lot of money for lawyers. At the most they may simply disappear into “rendition,” confinement in a country with low standards about torture and no habeas corpus.

True enough that setting fire to laboratories, liberating mink from “ranches,” setting loose millions of dollars of mice and destroying the experiments they support, are bad things to do and often come from people who are neither thoughtful nor helpful. They meant to be provocative and look what they provoked! But defining them as “terrorists” ups the ante enough to attract the truly nutso. Do we want people blowing themselves up in local animal shelters?

In the last wave of extravagant superrich industries, the 1900’s Age of Gold, which many writers are beginning to compare to right now in terms of growing wealth disparity, there was violence against workers, sabotage against factories, riots and assassinations enough to dislocate public order. Is this what we’re moving towards?

Many humane workers think that they’re trying to make everyone be gentle pacifists who never kill any animals anywhere. They never consider overgrazing, belligerent deer in towns, vicious animals, or anything else that interferes with their vision of life as naturally an Eden: a zipless, prelubricated, eternal childhood Land of Sunshine. Instead, their harassment of government and corporate bodies has irritated the latter enough for this kind of out-of- proportion overkill.

I understand the irritation. When I was doing animal control, there were always individuals who locked onto us as evil monsters, used sunshine laws to demand time-consuming and expensive compilations of records, got on talk shows to whip up emotion over incomplete versions of lamentable cases, and generally hounded us into plugging our ears. But they weren’t terrorists. And a few of them had good sense -- they could become valued allies and friends. Still, there was always a rough edge of law enforcement that muttered, “Those women need a good ...” you know. Only a short step from there to rape, which can hardly be separated from violent assault. If they’re “only” terrorists...

No newspaper has discussed this federal law. I see no articles in magazines about it. Journalism believes that animal stuff is for children. All that tiresome stuff -- so hard to sort out. So...well, icky.

They tell me -- and I guess I believe it -- that in France there is no law against cruelty on grounds of being inhumane. Rather it is illegal to offend the sensibilities of others through cruelty. In this country, we don’t care much about sensibilities. The great overriding consideration is the profit margin. It is increasingly illegal -- to the point of being considered terrorism -- to interfere with anyone’s profit margin. Crimes against the dollar are crimes against the State.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

A TRIP IN THE RANGER

For a while there, it appeared that the Sam Strachan family would make their fortune from crabgrass -- the elimination of it. Well, the attempted elimination of it. In fact, they were about to leave farming and become manufacturers, working as the agents of the Kovar Kultivator Kompany. The great success was a harrow designed for the pesky long-rooted quack grass. “Dry and die” was the motto of the horsedrawn machine that pulled them out of the ground so the sun could get at them.

From the Internet:

Crabgrass is a common weed that almost everyone knows. (The "great philosopher" Pogo said, "Work is the crabgrass in life."). {The Latin name, Digitaria, alludes to the finger-like spayed out ends.] Digitaria were introduced from Eurasia and are widespread throughout the United States. Crabgrass is found in turfgrasses (mostly smooth crabgrass) and in ornamental landscapes (primarily large crabgrass). Large crabgrass is also found in orchards, vineyards, and other agricultural areas. Crabgrass also has many other names including crowfoot grass and summer grass.

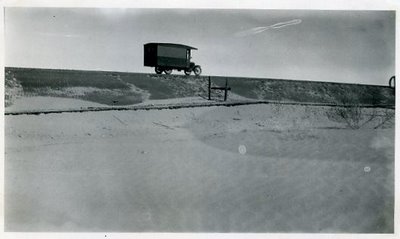

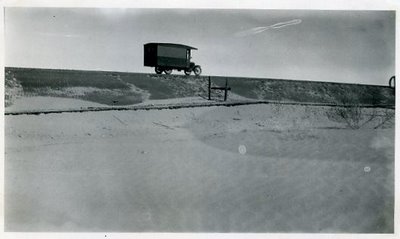

It was 1926 and the Sam Strachans had been married for twenty-five years. Sam built his own homemade version of an RV, a home on wheels they called “The Ranger,” and they set off to explore the Continent. Strachans never paid much attention to the 49th parallel, though it gave them trouble through tariffs at the border on their Kovar Kultivators. The tariffs would end the business but not yet. (If the tariffs hadn’t put Kovar out of business in Canada, the soon-to-come invention of herbicides would have anyway.)

After many adventures getting to Portland, that Christmas the couple lived in the Ranger on a parking lot across from the Congregational Church. Of course it rained the whole time, which Beulah, used to the high and dry prairie, thought was wonderful. She hung a bucket to the eaves and collected soft water for hand laundry. The two of them walked down to the waterfront where there were still sailing ships and they went to stage shows. In the daytime they separately patronized the YWCA and YMCA. Each of them kept journals which I’ve typed out and distributed around the family. It was quite like a second honeymoon, although they were so enmeshed and had been for so long, that there was no need for such an interval to restore their relationship. They just needed time away from the frontier prairie.

There were several stops to make through the Strachan diasphora. One was to Sam’s cousin, George Ramsey Jr., (the son of Sam’s mother’s sister Mary Welch who married George Ramsey Sr.), thriving in Victoria, B.C. (I have no b&d dates for these folks. The Welch girls were born and raised in Scotland in the last half of the 19th century.) Across the street from the very substantial Ramsey house was another, and looming over it was Craigdarroch Castle. Sam took a photo from the top floor of the Ramsey house. It didn’t look like the little pink Pickler mansion.

Cousin Will Harcus, son (or husband?) of Jean Ramsey daughter of Mary Welch Ramsey lived in Everett in a rather less palatial house.

A South Dakota neighbor, Will Jackman, also had a pleasant house nearby.

The Sam Strachan’s appear to have kept up their relationships with the homestead neighbors as much as they did with their genetic diasphora. Which are stronger: bonds of blood or bonds of shared experiences? Best is when the two are entwined. Which draws people closer together, hardship or good fortune? Hard to tell. Maybe hardship.

Having taken a good look at the Pacific Northwest, the travelers swung down to Purcell, Oklahoma, where Sam’s mother and her sisters and Sam’s sister Jeannie (1877-1957) -- a second wife to the widowed Harmon Archer (1869 - 1942) -- were living. Sam’s mother, Catherine Welsh Strachan (b.1852), was buried there in 1918 and Sam had taken his father Archibald’s body (b. 1850) to her side in 1926. Matt Robertson (1880 -1967), a cousin who is in this photo and who referred to Archibald as “Uncle Archie,” had a story about Uncle Archie’s small brother, whose leg had to be amputated for some reason. After a while, when the boy had recovered somewhat, he asked when his new leg would begin to grow back. An optimist, that boy! I have no idea what his first name was or what eventually happened to him.

Matt, who was a lawyer and probably could have been a writer, said that on the Welsh side the family was descended from John Knox, the great Scotch reformer, through his second wife. Matt said he was of the 11th generation but couldn’t prove it. Also, he claimed as ancestors King Robert the Bruce of Scotland and William Wallace, the Scots hero of the 12th Century. Jane Welsh, wife of Thomas Carlyle, and Jane Welsh, wife of Alexander Hamilton, were also claimed. There is a long story about John Brown Gillis and his children, which I won’t include here.

Harmon Archer’s house is also quite romantic, with gingerbread on the eaves, a square tower with a not-quite spire, and unique windows. The family often spoke of the “round window.” Note the amenity of the screen porch at the rear. The front porch, concrete, is rather Greek with its curves and columns. I believe Jeannie Archer lived here all her life after marrying in 1907, so that means she was in residence for fifty years. Her sister Jessie stayed in South Dakota -- quite a different life.

Beulah and Sam returned to the far north, encouraged by the success of others and with renewed confidence that there was still time to succeed themselves. They would make several other swings around the continent, to Ottawa, New England, and to Alberta. Even a visit back to South Dakota. They had escaped John Knox and his dour Scots devotion to duty.

From the Internet:

Crabgrass is a common weed that almost everyone knows. (The "great philosopher" Pogo said, "Work is the crabgrass in life."). {The Latin name, Digitaria, alludes to the finger-like spayed out ends.] Digitaria were introduced from Eurasia and are widespread throughout the United States. Crabgrass is found in turfgrasses (mostly smooth crabgrass) and in ornamental landscapes (primarily large crabgrass). Large crabgrass is also found in orchards, vineyards, and other agricultural areas. Crabgrass also has many other names including crowfoot grass and summer grass.

It was 1926 and the Sam Strachans had been married for twenty-five years. Sam built his own homemade version of an RV, a home on wheels they called “The Ranger,” and they set off to explore the Continent. Strachans never paid much attention to the 49th parallel, though it gave them trouble through tariffs at the border on their Kovar Kultivators. The tariffs would end the business but not yet. (If the tariffs hadn’t put Kovar out of business in Canada, the soon-to-come invention of herbicides would have anyway.)

After many adventures getting to Portland, that Christmas the couple lived in the Ranger on a parking lot across from the Congregational Church. Of course it rained the whole time, which Beulah, used to the high and dry prairie, thought was wonderful. She hung a bucket to the eaves and collected soft water for hand laundry. The two of them walked down to the waterfront where there were still sailing ships and they went to stage shows. In the daytime they separately patronized the YWCA and YMCA. Each of them kept journals which I’ve typed out and distributed around the family. It was quite like a second honeymoon, although they were so enmeshed and had been for so long, that there was no need for such an interval to restore their relationship. They just needed time away from the frontier prairie.

There were several stops to make through the Strachan diasphora. One was to Sam’s cousin, George Ramsey Jr., (the son of Sam’s mother’s sister Mary Welch who married George Ramsey Sr.), thriving in Victoria, B.C. (I have no b&d dates for these folks. The Welch girls were born and raised in Scotland in the last half of the 19th century.) Across the street from the very substantial Ramsey house was another, and looming over it was Craigdarroch Castle. Sam took a photo from the top floor of the Ramsey house. It didn’t look like the little pink Pickler mansion.

Cousin Will Harcus, son (or husband?) of Jean Ramsey daughter of Mary Welch Ramsey lived in Everett in a rather less palatial house.

A South Dakota neighbor, Will Jackman, also had a pleasant house nearby.

The Sam Strachan’s appear to have kept up their relationships with the homestead neighbors as much as they did with their genetic diasphora. Which are stronger: bonds of blood or bonds of shared experiences? Best is when the two are entwined. Which draws people closer together, hardship or good fortune? Hard to tell. Maybe hardship.

Having taken a good look at the Pacific Northwest, the travelers swung down to Purcell, Oklahoma, where Sam’s mother and her sisters and Sam’s sister Jeannie (1877-1957) -- a second wife to the widowed Harmon Archer (1869 - 1942) -- were living. Sam’s mother, Catherine Welsh Strachan (b.1852), was buried there in 1918 and Sam had taken his father Archibald’s body (b. 1850) to her side in 1926. Matt Robertson (1880 -1967), a cousin who is in this photo and who referred to Archibald as “Uncle Archie,” had a story about Uncle Archie’s small brother, whose leg had to be amputated for some reason. After a while, when the boy had recovered somewhat, he asked when his new leg would begin to grow back. An optimist, that boy! I have no idea what his first name was or what eventually happened to him.

Matt, who was a lawyer and probably could have been a writer, said that on the Welsh side the family was descended from John Knox, the great Scotch reformer, through his second wife. Matt said he was of the 11th generation but couldn’t prove it. Also, he claimed as ancestors King Robert the Bruce of Scotland and William Wallace, the Scots hero of the 12th Century. Jane Welsh, wife of Thomas Carlyle, and Jane Welsh, wife of Alexander Hamilton, were also claimed. There is a long story about John Brown Gillis and his children, which I won’t include here.

Harmon Archer’s house is also quite romantic, with gingerbread on the eaves, a square tower with a not-quite spire, and unique windows. The family often spoke of the “round window.” Note the amenity of the screen porch at the rear. The front porch, concrete, is rather Greek with its curves and columns. I believe Jeannie Archer lived here all her life after marrying in 1907, so that means she was in residence for fifty years. Her sister Jessie stayed in South Dakota -- quite a different life.

Beulah and Sam returned to the far north, encouraged by the success of others and with renewed confidence that there was still time to succeed themselves. They would make several other swings around the continent, to Ottawa, New England, and to Alberta. Even a visit back to South Dakota. They had escaped John Knox and his dour Scots devotion to duty.

Monday, November 20, 2006

MANITOBA AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE

From the Internet:

Manitoba Agricultural College

After 1905 the agricultural education movement on the prairies was strengthened when the province of Manitoba established the Manitoba Agricultural College.

It might be argued that the objectives of the College had less to do with teaching students how to farm as then with equipping those who already knew how to farm with the scientific and management tools to make them better farmers. The College offered a core curriculum of coures in horticulture and field husbandry, agricultural engineering, animal husbandry, and natural history. In addition to these practically oriented courses, programmes were offered in the fields of agricultural economics, accounting and farm management, courses which reflected the increasing professionalization of farming.

Alongside the faculties that taught farming practises, MAC offered course in Household Sciences and Home Economics. This home economics division offered courses in foods and nutrition, clothing and textiles, physiology and hygiene and institutional management to women, and reflected a growing professionalization of the domestic sphere in rural society.

In addition to being a centre of teaching, the College was a centre of research and experimentation. College agronomists conducted research into agricultural techniques, inventing and improving machinery, determining the optimal methods for weed and insect control, tillage and ploughing, and crop rotation.

The College was also a primary instrument of agricultural education beyond its own classrooms and laboratories, and it counted among its objectives to bring news of agricultural developments to the attention of established farmers. The College sponsored field experiments and demonstration crops on private farms. It conducted extension courses, lecture series and practical demonstrations at which farmers could learn more about soil and moisture conservation, traction engineering, seed cleaning, and other aspects of modern farming. Between 1912 and 1914, these educational programmes took to the rails, as the College co-operated with the Agricultural Extension Services to send two Better Farming Trains across the province.

Since in Minitonas in 1924 the Strachans were raising row crops (onions, potatoes, raspberries) with horse-drawn machinery (the kind on which one sits, holding reins) and living in modest houses, Bruce must have been in a state of shock for the first months at Manitoba Agricultural College in Winnipeg. Huge blocky buildings sitting in straight lines south of Winnipeg were so new there was neither lawn nor landscaping. The campus looks rather Soviet. The first thing he did was go to the top of each building and take a photo of the other buildings from the top. The first impulse of most folks would be to stand before the entrance and take a photo looking up at the building, but I don’t see a single photo like that. Bruce was a freshman at age 23, evidently preferring to look at the larger layout -- and perhaps to keep some distance.

But the phenomenon of the Edenic, protected, inside over-against the monolithic, stony, forbidding outside is present at its most extreme in the horticulture building with its greenhouses. Inside is lush and blooming summer, nothing like the subzero of outdoors. The seduction of such a sheltered place cannot be overestimated.

In 1925 Glenn also attends college here and thus is able to photograph his big brother Bruce at the top of the 100 foot CKY radio tower while the latter photographs the campus from his perch. At the end of the first term, Bruce averages 82% and Glenn averages 84%. These scores are the highest in their respective classes. The next highest scores are several points lower. Despite their literal high-jinks, they work hard.

I don’t know whether they were atypically older or whether this was a common phenomenon in that setting, but I do believe they were proud, nearly to the point of arrogance. What kept the lid on them was a strong near-communist sense of social responsibility and political obligation to others. They had a keen sense of community and neighborhood, for the excellent reason of having saved each other over the years. This was the Roaring Twenties, sure enough, (probably rather muffled in Winnipeg, though even today that city has an avant garde edge), but there was also an element like the Sixties -- an appetite for experiment and a Peace Corps-like drive to reform and develop. My father was enthralled by people like Bertrand Russell and Margaret Sanger, but his idealism was not theoretical so much as it was practical. Rodale, the organic gardener, was in there with Freud. The prairie Strachans knew what hard times were like.

Traveling home on the train from school, my father’s resources had been reduced to 26 cents. Combining his knowledge of nutrition with a desire for value, he spent the money on a big bag of redskin peanuts to eat on the long trip. Throughout his life he kept a little cache of redskin peanuts as a buffer against starvation. I do the same.

Manitoba Agricultural College

After 1905 the agricultural education movement on the prairies was strengthened when the province of Manitoba established the Manitoba Agricultural College.

It might be argued that the objectives of the College had less to do with teaching students how to farm as then with equipping those who already knew how to farm with the scientific and management tools to make them better farmers. The College offered a core curriculum of coures in horticulture and field husbandry, agricultural engineering, animal husbandry, and natural history. In addition to these practically oriented courses, programmes were offered in the fields of agricultural economics, accounting and farm management, courses which reflected the increasing professionalization of farming.

Alongside the faculties that taught farming practises, MAC offered course in Household Sciences and Home Economics. This home economics division offered courses in foods and nutrition, clothing and textiles, physiology and hygiene and institutional management to women, and reflected a growing professionalization of the domestic sphere in rural society.

In addition to being a centre of teaching, the College was a centre of research and experimentation. College agronomists conducted research into agricultural techniques, inventing and improving machinery, determining the optimal methods for weed and insect control, tillage and ploughing, and crop rotation.

The College was also a primary instrument of agricultural education beyond its own classrooms and laboratories, and it counted among its objectives to bring news of agricultural developments to the attention of established farmers. The College sponsored field experiments and demonstration crops on private farms. It conducted extension courses, lecture series and practical demonstrations at which farmers could learn more about soil and moisture conservation, traction engineering, seed cleaning, and other aspects of modern farming. Between 1912 and 1914, these educational programmes took to the rails, as the College co-operated with the Agricultural Extension Services to send two Better Farming Trains across the province.

Since in Minitonas in 1924 the Strachans were raising row crops (onions, potatoes, raspberries) with horse-drawn machinery (the kind on which one sits, holding reins) and living in modest houses, Bruce must have been in a state of shock for the first months at Manitoba Agricultural College in Winnipeg. Huge blocky buildings sitting in straight lines south of Winnipeg were so new there was neither lawn nor landscaping. The campus looks rather Soviet. The first thing he did was go to the top of each building and take a photo of the other buildings from the top. The first impulse of most folks would be to stand before the entrance and take a photo looking up at the building, but I don’t see a single photo like that. Bruce was a freshman at age 23, evidently preferring to look at the larger layout -- and perhaps to keep some distance.

But the phenomenon of the Edenic, protected, inside over-against the monolithic, stony, forbidding outside is present at its most extreme in the horticulture building with its greenhouses. Inside is lush and blooming summer, nothing like the subzero of outdoors. The seduction of such a sheltered place cannot be overestimated.

In 1925 Glenn also attends college here and thus is able to photograph his big brother Bruce at the top of the 100 foot CKY radio tower while the latter photographs the campus from his perch. At the end of the first term, Bruce averages 82% and Glenn averages 84%. These scores are the highest in their respective classes. The next highest scores are several points lower. Despite their literal high-jinks, they work hard.

I don’t know whether they were atypically older or whether this was a common phenomenon in that setting, but I do believe they were proud, nearly to the point of arrogance. What kept the lid on them was a strong near-communist sense of social responsibility and political obligation to others. They had a keen sense of community and neighborhood, for the excellent reason of having saved each other over the years. This was the Roaring Twenties, sure enough, (probably rather muffled in Winnipeg, though even today that city has an avant garde edge), but there was also an element like the Sixties -- an appetite for experiment and a Peace Corps-like drive to reform and develop. My father was enthralled by people like Bertrand Russell and Margaret Sanger, but his idealism was not theoretical so much as it was practical. Rodale, the organic gardener, was in there with Freud. The prairie Strachans knew what hard times were like.

Traveling home on the train from school, my father’s resources had been reduced to 26 cents. Combining his knowledge of nutrition with a desire for value, he spent the money on a big bag of redskin peanuts to eat on the long trip. Throughout his life he kept a little cache of redskin peanuts as a buffer against starvation. I do the same.

Sunday, November 19, 2006

MANITOBA HOME

This farmhouse is in West Favelle, Minitonas, Manitoba. My father’s caption says, “Winter comes in October.” The date is October, 1919. This is not prairie, but rather scrubby brush that shelters bears and moose. The first winter, when money was short, they subsisted largely on canned moose.

The bears, like the Strachans, climbed the poplars. The Strachans, unlike the bears, climbed each other, the house, and whatever else there was. Growing up on the horizontal, they were fascinated by the vertical. This caption says, “Looking at the claw marks after a bear climbed this tree.” They did a bit of logging and a photo of a wagon-load of logs notes that the biggest log they cut was 27” across.

This house is taller than the South Dakota house and the added-on shed has a stepped roof (or edge) instead of slanted. The chimney is at the shed end of the house, so maybe the kitchen is in the shed, sharing the chimney with a heating stove in the front. Note the stained glass embellishment on the upper parts of the windows. (I’m impressed that in English movies the houses always have lots of stained glass, so maybe it’s an English predeliction.) Again there’s no porch.

Winter here was very hard. My father remembered it as a constant round of carrying out ashes and clinkers to put on the paths to sheds and outhouses and then carrying in more coal. There are always coal deposits on the high prairie if you know where to look. Even in the mild climate of Portland, OR, he would not give up the coal furnace, even after it became impossible to buy coal. (Finally my mother had the furnace removed while he was out of town.)

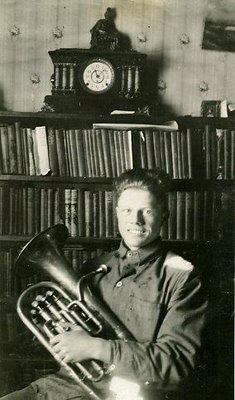

Even far to the north indoors was snug and safe. The result of having four nearly-grown children in a house this size was that things were a tiny bit crowded. In this house most photos were taken against this bookshelf with the mantel clock at the top, which I take to be a substitute because they are heating with a stove rather than an inefficient fireplace. Still, this family considered writing as important as fire. The mantel clock continued on to May’s household eventually, and the Bruce Strachan’s also had a plainer one which wasn’t sold until my mother died in 1999. The clock in this photo has a bronze portrait of a seated woman at the top, wearing Greek draped clothing. Probably she is meant to represent “Wisdom,” though I think I was once told she was “Minerva,” approximately the same thing. The books in the shelves look to be bound reports rather than popular books: the size of typing paper, but slim.

Mircea Eliade and other writers have pointed out that what the family values often becomes a kind of household altar: a piano, a staircase, a big window, a fine painting. In this house it’s pretty clear that classical time and books are the sacred objects. One photo after another is taken with this book case as background. (The camera case is hanging to the far right next to the calendar. I remember it from my own childhood. It was a bellows camera that made "post card" photos.) Of course, part of the reason is that this is an available-light time-exposure, so the windows need to be behind the camera or the result will only be silhouettes.

The sibs are probably doing homework -- May actually typing! But the caption says, “The family holds court.” That’s just a way of saying everyone is there and attentive, but it does look rather as though Bruce is the judge, sitting up high, May is the court stenographer and the two boys -- well, are they culprits or lawyers? Maybe they combine and swap the roles. They were in cahoots quite a lot.

Here’s Glenn with his horn, seated in front of the domestic altar. One can see the goddess and the sacred texts -- not quite the titles on the spines. Or maybe you have sharper eyes than mine.

The Strachan families that resulted from these sibs did tend to be self-contained and to feel that they were special, just by being Strachans. They were literate, they all worked hard on the farm, they saw nothing but progress ahead. No one had a clue that the youngest boy, Seth, with his love of heights, would end up as a bomber and transport pilot (B52's and B59's) in World War II, though they had admired the barnstormers in their little canvas and bamboo flying machines when they visited South Dakota prairie after WWI.

This photo actually begins a different essay, about touring the West in a homemade RV, probably funded by the estate of Archibald. I'm unsure whether this is the back of the same house, improved with a second chimney and porch, or simply another house. There are many hints about economic problems: good crops lead to low prices, you know.

Saturday, November 18, 2006

"GREY & GOLD"

“GREY AND GOLD” 1942 by John Rogers Cox

A copy of this painting hung on our wall when I was growing up. It was an icon signifying my father’s boyhood in South Dakota. (My mother had her own, a photograph of sheep in the hills of Douglas County.) The book cover I’ve scanned here is called “Illusions of Eden, Visions of the American Heartland.” It’s actually a catalogue to accompany a show of art works and was sponsored by Phillip Morris. It’s in three languages: English, Hungarian, and German. I haven’t sat down to the read the book, but I did read the bio of Cox (1915-1990) and the information at AskArt.com, much of which is on the bulletin board section as messages from friends and former students. His work is considered to be “magic realism,” realer than real. His later years were spent in Washington State, in Wenatchee, though he was born in Indiana and taught in Chicago at the Art Institute for a long time. The example of his work on AskArt.com shows he detected a twisted and demonic side to the prairies as well as this orderly but foreboding landscape. Surrealists always seem to have a kind of horror-film side. Or is it the other way around?

This painting won the second medal in the “Artists for Victory” exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Two years later the same painting received the “popular prize” in the exhibition, “Painting in the United States, 1944,” held at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh. This painting now resides in the permanent collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

I don’t know whether my father knew all this stuff or what he made of it. His connection was just straight from the heart and my mother honored it. Over our fireplace was a “painting” (actually a print with a nice frame) that my parents bought together. I was present for the discussion of whether to buy it, but had no input. I was very small, but was impressed by their seriousness. A swan swims in a pond, looking very much like Laurelhurst Park, which I thought it was until I was grown up. It was to stand for their joy at living in Portland, Oregon, where we often picnicked in this park. My Aunt May and Uncle Doc also had a nice “painting” on their wall that looked very much like the prairie parkland of northern Canada. It was poplars in winter with snow and when the family gathered there, they would discuss whether the light was meant to be winter sun or moonlight. That signalled the beginning of the stories about Manitoba.