My life has been centered and guided by something so corny that I hate to tell you about it, in a way. But I love to talk about it, too. I fell in love. Go ahead and groan. In my twenties in Montana I felt I was in the grip of a Grand Passion. It couldn’t continue, but I thought religious leadership might be like that.

Since I’m using the word “passion,” I looked it up in the New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. There are inter-related kinds of meaning: religious martyrdom (like Mel Gibson’s movie), disease or affliction, and sexual desire. What a trinity! Until Gibson reminded us, we didn’t think much about religious passion. The sense of passion as a disease seems to be dying out. But passion as sex almost overwhems us every time we key into the media. Always presented as a “good.”

Next I looked up the word in the New International Webster’s Student Dictionary of the English Language, a little paperback I keep by the computer. It defines passion thus:

1. Fervent devotion.

2. Ardent sexual feelings and desire. Love.

3. The object of such feelings.

4. A fit of intense anger, rage.

5. Any transport of excited feeling.

6. Archaic: Suffering, agony.

Pretty confusing. Looks like “passion” has become one of those slushy words used for too many things, which leads to muddled thinking even for people at seminary trying to confront such realities as sex and faith.

Seminary is for four years. Some seminarians had “affairs” while there -- lonesome, needy, pretty easy. But one expects to change. One is gone a whole summer for CPE in a hospital. One is gone for a whole year for internship in a totally different place. Then one leaves for the first church pulpit and doesn’t see anyone from seminary again until maybe the annual General Assembly. How practical is a relationship under such circumstances? It would have to be broken off in a few years at most. My rule has been not to embark on an intimacy unless the intention was to make it permanent. This rule wasn’t moral, it was self-protective. I can’t stand the pain. Sex without intimacy is unthinkable for me, but my cohort of younger people didn’t agree at all. They’re on the other side of the Sexual Revolution.

At CPE the supervisor said we were all too uptight about sex and a number of different CPE groups were gathered to watch Glide Methodist Foundation sex films. (That particular church was “farther out” than any Unitarian church of the time and place. The only church farther out was Jim Jones’.) They are simply movies of people fucking -- each with its own little theme -- some married, some not, one impossible tropical encounter which consisted of many acts of intercourse edited together so they seemed like one long event, and one showing a couple past retirement age -- augmented with a vibrator. (That was before Viagra.) There was no story or even dialogue. The supervisors were particularly interested in the reactions of one group which was mostly nuns. This was supposed to prepare us for marriage counselling. That’s not the hit I got off it.

In Portland, in the Seventies, I was thirty, newly divorced. I set out to do some exploring and joined a “peoples’ consciousness-raising group” where we boldly discussed everything. The group leaders were a conscientious, happily married, educated, young Jewish couple. Desperate for a job, the husband was selling tickets at a porn movie house. Feeling confident with him in the lobby, we saw “Behind the Green Door,” “Deep Throat,” and other porn classics. There was an erotic film festival at Portland State University where there were lesbian films but no S/M. In fact, the discussion was all against violence. (“Make peace, not war.”) One of the Glide Methodist films was shown. (The one with the young married couple who went around on motorcycles, then made love next to a swimming pool and dozed until the man threw the woman in the water without her expecting it. Feminists were VERY vehement about mixing this violence with love. The CPE supervisors had never brought up this political subject.) In all the years since, I’ve never found any of the stuff in those movies useful in marriage counseling.

At seminary a brochure came in the mail advertising a Masters and Johnson workshop. For a joke, the office mail sorter put it in my box, thinking that I was the least likely of anyone to be having sex. But I attended. It WAS useful. Even though the very tall lady next to me wearing all powder blue, including her elegant hat, acquired a dark-blue case of five o’clock shadow, she had excellent ideas.

I had read Kinsey, all the Masters and Johnson books, Freud, and Kraff-Ebing -- my father owned them and I read them too young. I would not have been too young if someone had talked to me intelligently about the material, but I wasn’t known to be reading it. Anyway, I don’t think he ever really assimilated all that stuff either.

No one at seminary talked about passion, intense emotion, overwhelming love. Not in regard to people, not in regard to issues, or even spirituality. When I first started seminary, we went to a Get Acquainted party at a faculty member’s house, and afterwards my classmates jumped all over me because I was too enthusiastic. They said I embarrassed them with my lack of cool. Didn’t I know that tipped off the faculty that I was WEAK? Excessive strong feeling seemed to cause a great deal of ambivalence in what one man exasperated with Unitarians called “God’s frozen people.” (Not his joke. It’s historical and related to the roots of the denomination in Boston.) It was hinted that I was “over-earnest.” I must find “balance.” I shouldn’t “care so much.” We were to be liberal, tolerant, and not interfere in other cultures. Sort of like “Star Trek.”

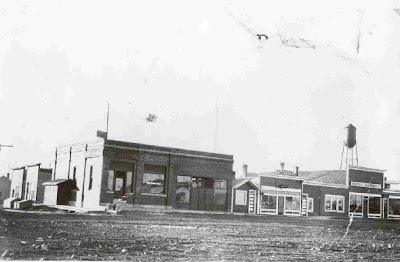

So here I am, retired, in this little village of 350 souls (Lutheran, Methodist, Catholic and Jehovah’s Witness). It’s going to be deeply subzero tonight. I haven’t talked to anyone all day since I mailed some books this morning. I don’t have TV so I listen to public radio all day. I probably won’t have enough money to pay the heating bill this month. Yet I’ve never felt so confident, so in touch with a huge network of people, so appreciative of the mountains on the horizon, so eager to write.

It’s a Great Passion, the certainty that I’m part of everything -- the lecture that just ended, the symphony that’s just beginning, the cats making their pre-bedtime rumpus, the blizzard now sweeping down over the prairie. I was always here. When I die, I will still be here. My immortality comes through participation in everything and everything may transform but it will never end. The orgy around me is Schweitzer’s “life in the midst of life, life that wishes to live.”

Fervent devotion. Yes.

Ardent sexual feelings and desire. Love. Well -- does sublimation and memory count?

The object of such feelings. I’m not concerned with objects.

A fit of intense anger, rage. Does political stuff count? It’s not my passion and it’s not sexy, but it becomes increasingly outrageous.

Any transport of excited feeling. It’s opera day, the sun is streaming over the snow, it may be that my pickup radiator survived fifty-below after all.

Archaic: suffering, agony. I won’t take this seriously for myself, but I’m acutely aware of it in this and other communities.

Maybe I should go back to seminary, now that I’ve thought all this over in the twenty-near-thirty years since. They say education is wasted on the young. These days forty seems quite young. I won’t go back -- I’ll just order books. My Grand Passion is here now. Once a parishioner’s therapist told her to ask to be part of my secret life. A little shocked (WHAT secret life?) I told her okay. But she should bring her own book. We might not be on the same page.

Wednesday, January 31, 2007

Tuesday, January 30, 2007

TRAUMA

Serving the ER was much more exciting than going down the hallway greeting victims of chronic problems. ER is the stuff of drama, right? Be sure to wear the shirt with the reversed collar.

What if the chaplain gets traumatized? Right in front of everyone?

The town where the hospital was had a thing for lawns. People lived and died for their lawns. There was a lawn-of-the-month competition and the winner got to have a sign in the yard. It folded to stand up so that it wouldn’t be necessary to drive a stake into the grass. ER called me because of a mother who had just run over her four year old son with a riding mower. The blades mostly just chopped his foot. I walked into a room where the screaming child was being held down by his mother and the nurse while they waited for the doctor. The foot was pulped.

“Omigod,” I blurted. “Will he lose the foot?” The nurse shot eye-daggers at me. The mother said through her teeth, “We don’t know.” The child, understanding exactly what I said, fixed his eyes on mine and his screaming went an octave higher. The doctor came, a shot was given to the boy to slip him into unknowing and the nurse ORDERED me to take the mother out and get her coffee.

I did and collected myself enough to sit and talk more coherently. She began to shake and weep, now that she wasn’t on duty, and told me how she hadn’t even known her son was outside the house. She’d been backing up a few feet to make a sharp turn. The boy was determined to ride with her and ran up behind her. He’d been told a thousand times not to come near. I apologized for my tactless question. Gracefully, she said, “You only said what we were all thinking. Maybe it’s better for it to be out in the open.”

So one thing that happens when the chaplain freaks out, is that others take up the ministry.

Once I was flummoxed when I went to a farm family who had just lost the grandma. Four generations sat somberly in the “family room,” but the grandpa was laughing merrily. The others stared at the floor while I told the old man that I was sorry for his loss. “She was a good ol’ gal!” he told me, grinning. Some of the women were weeping.

I figured there was some kind of strange crossed-wires in the old man’s head. We visited about the “good ol’ gal” a little more, we prayed, and I left. I read about it. Not uncommon. Not necessarily something diagnosable like Alzheimer’s, just a startling reaction. Not really traumatic and not even a symptom of shock in this old man, though maybe he was taking shelter in unreality for a little while.

We had been told that black people, especially those from the rural south, might be very physical in their grief reaction. We should be ready for them to throw themselves against the walls or floor or furniture and to make sure they didn’t hurt themselves. A mother had just learned that her teenaged daughter, who had a heart defect she knew might kill the girl at any time, had actually died. She collapsed to the floor.

I’d seen “nurses” in white uniforms ministering to the overcome at intense evangelical rallies, especially in hot weather, so I’d brought along a damp washcloth. I knelt behind the woman with my arms around her and tried to soothe her face with the cloth. It did seem to help. For a moment I could feel in her the impulse to fling herself around so I hugged her from behind, holding her against me. Then she seemed to come to herself. “Let me up,” she said, and I did. Family members were there. In a while I left and I think she was glad to see me go. It was as though I’d prevented her from grieving properly.

Another incident was so shocking that decades later I’m still not over it. An older grandmotherly woman had come in for repair to varicose veins. Behind the nursing station was an examination room and she had been taken in there for a pelvic exam. At the time I couldn’t understand why she needed a pelvic for varicose veins and no one could tell me anything except, “It’s standard procedure.” Lately I’ve been reading articles saying that in teaching hospitals, in order to give student doctors experience, women who are unconscious for other reasons are often given pelvics without the knowledge or permission of the patient or family. Who could it hurt? Isn’t a pelvic a benign preventative strategy? After all, there was no charge for it in such cases.

The problem was that when they put the woman’s feet up in the stirrups, they dislodged a clot that killed her instantly. When I got there, this obese, late-middle-aged, white-haired woman was being given Code Blue resuscitation with all the vigor it was possible to muster. It was desperate. Her gown had been torn off and thrown to the floor, her arms were extended, her legs still in the stirrups with her private parts towards the door which stood open because there were too many people and too much equipment in the small room to shut it. There were tubes and syringes and racks of drips and the shock machine. Everyone was shouting, people ran past with samples of blood, and everyone’s face was frozen in shock. It looked more like a murder than a rescue.

I stood there with a weak smile on my face, no idea what to do, unable to understand what was going on. A ward nurse came up to me, angry. “Go to the elevator and intercept the family. DO NOT let them come here until we tell you it’s all right.” I did that successfully, though they had many questions and their impulse was to go to their mother. A short time ago they had dropped “Mother” off for what they thought was minor surgery and now they had been told that she was in extreme danger -- NOT that she was dead. A man I took to be her son was a tall, very handsome, “silver fox” rancher in cowboy hat and boots. The grown children were very quiet, almost paralyzed.

Finally word came that Mother had passed on. The family could visit. She was dressed in her own nightie, her teeth were back in her mouth, and she was peacefully arranged in a clean bed. She seemed just an old lady who had died of natural causes. The Silver Fox turned out to be her husband. He threw himself onto the woman and deeply kissed her over and over, almost like artificial resuscitation. Then, bouncing off the walls and wailing, he called, “Mommie, Mommie, Mommie” like a little child. His children stood away from him. I stood away from him.

A small black nurse, one of the most effective on that ward, came storming in the door and grabbed him in a fierce embrace. “It’s all right. She’s in Heaven with God! She’s at peace!” She rocked this poor man while over his shoulder she glared at stupid me who couldn’t think of what to say. I was still wondering if the hospital was going to lose a bundle in the lawsuit. Would I have to testify? Like that old man who giggled over the loss of his wife, I had taken flight from the real present.

But I still wonder about that man and his wife. What was the story of their relationship? Could I develop it into a novel? This is my way of dealing with my own shortcomings -- write them out, create a new set of events, invent a character who can forgive me, since it’s so hard to forgive myself. Maybe ministering to oneself is hardest of all, which is why one needs colleagues and mentors. But often they are too far away. Or it's too hard to admit one's own shortcomings.

What if the chaplain gets traumatized? Right in front of everyone?

The town where the hospital was had a thing for lawns. People lived and died for their lawns. There was a lawn-of-the-month competition and the winner got to have a sign in the yard. It folded to stand up so that it wouldn’t be necessary to drive a stake into the grass. ER called me because of a mother who had just run over her four year old son with a riding mower. The blades mostly just chopped his foot. I walked into a room where the screaming child was being held down by his mother and the nurse while they waited for the doctor. The foot was pulped.

“Omigod,” I blurted. “Will he lose the foot?” The nurse shot eye-daggers at me. The mother said through her teeth, “We don’t know.” The child, understanding exactly what I said, fixed his eyes on mine and his screaming went an octave higher. The doctor came, a shot was given to the boy to slip him into unknowing and the nurse ORDERED me to take the mother out and get her coffee.

I did and collected myself enough to sit and talk more coherently. She began to shake and weep, now that she wasn’t on duty, and told me how she hadn’t even known her son was outside the house. She’d been backing up a few feet to make a sharp turn. The boy was determined to ride with her and ran up behind her. He’d been told a thousand times not to come near. I apologized for my tactless question. Gracefully, she said, “You only said what we were all thinking. Maybe it’s better for it to be out in the open.”

So one thing that happens when the chaplain freaks out, is that others take up the ministry.

Once I was flummoxed when I went to a farm family who had just lost the grandma. Four generations sat somberly in the “family room,” but the grandpa was laughing merrily. The others stared at the floor while I told the old man that I was sorry for his loss. “She was a good ol’ gal!” he told me, grinning. Some of the women were weeping.

I figured there was some kind of strange crossed-wires in the old man’s head. We visited about the “good ol’ gal” a little more, we prayed, and I left. I read about it. Not uncommon. Not necessarily something diagnosable like Alzheimer’s, just a startling reaction. Not really traumatic and not even a symptom of shock in this old man, though maybe he was taking shelter in unreality for a little while.

We had been told that black people, especially those from the rural south, might be very physical in their grief reaction. We should be ready for them to throw themselves against the walls or floor or furniture and to make sure they didn’t hurt themselves. A mother had just learned that her teenaged daughter, who had a heart defect she knew might kill the girl at any time, had actually died. She collapsed to the floor.

I’d seen “nurses” in white uniforms ministering to the overcome at intense evangelical rallies, especially in hot weather, so I’d brought along a damp washcloth. I knelt behind the woman with my arms around her and tried to soothe her face with the cloth. It did seem to help. For a moment I could feel in her the impulse to fling herself around so I hugged her from behind, holding her against me. Then she seemed to come to herself. “Let me up,” she said, and I did. Family members were there. In a while I left and I think she was glad to see me go. It was as though I’d prevented her from grieving properly.

Another incident was so shocking that decades later I’m still not over it. An older grandmotherly woman had come in for repair to varicose veins. Behind the nursing station was an examination room and she had been taken in there for a pelvic exam. At the time I couldn’t understand why she needed a pelvic for varicose veins and no one could tell me anything except, “It’s standard procedure.” Lately I’ve been reading articles saying that in teaching hospitals, in order to give student doctors experience, women who are unconscious for other reasons are often given pelvics without the knowledge or permission of the patient or family. Who could it hurt? Isn’t a pelvic a benign preventative strategy? After all, there was no charge for it in such cases.

The problem was that when they put the woman’s feet up in the stirrups, they dislodged a clot that killed her instantly. When I got there, this obese, late-middle-aged, white-haired woman was being given Code Blue resuscitation with all the vigor it was possible to muster. It was desperate. Her gown had been torn off and thrown to the floor, her arms were extended, her legs still in the stirrups with her private parts towards the door which stood open because there were too many people and too much equipment in the small room to shut it. There were tubes and syringes and racks of drips and the shock machine. Everyone was shouting, people ran past with samples of blood, and everyone’s face was frozen in shock. It looked more like a murder than a rescue.

I stood there with a weak smile on my face, no idea what to do, unable to understand what was going on. A ward nurse came up to me, angry. “Go to the elevator and intercept the family. DO NOT let them come here until we tell you it’s all right.” I did that successfully, though they had many questions and their impulse was to go to their mother. A short time ago they had dropped “Mother” off for what they thought was minor surgery and now they had been told that she was in extreme danger -- NOT that she was dead. A man I took to be her son was a tall, very handsome, “silver fox” rancher in cowboy hat and boots. The grown children were very quiet, almost paralyzed.

Finally word came that Mother had passed on. The family could visit. She was dressed in her own nightie, her teeth were back in her mouth, and she was peacefully arranged in a clean bed. She seemed just an old lady who had died of natural causes. The Silver Fox turned out to be her husband. He threw himself onto the woman and deeply kissed her over and over, almost like artificial resuscitation. Then, bouncing off the walls and wailing, he called, “Mommie, Mommie, Mommie” like a little child. His children stood away from him. I stood away from him.

A small black nurse, one of the most effective on that ward, came storming in the door and grabbed him in a fierce embrace. “It’s all right. She’s in Heaven with God! She’s at peace!” She rocked this poor man while over his shoulder she glared at stupid me who couldn’t think of what to say. I was still wondering if the hospital was going to lose a bundle in the lawsuit. Would I have to testify? Like that old man who giggled over the loss of his wife, I had taken flight from the real present.

But I still wonder about that man and his wife. What was the story of their relationship? Could I develop it into a novel? This is my way of dealing with my own shortcomings -- write them out, create a new set of events, invent a character who can forgive me, since it’s so hard to forgive myself. Maybe ministering to oneself is hardest of all, which is why one needs colleagues and mentors. But often they are too far away. Or it's too hard to admit one's own shortcomings.

Monday, January 29, 2007

NOTES

In the beginning my idea was that this blog would be focused on this geographical area but I find I'm tempted to stray, and right now I'm going to stray more than a little bit. I've just had some essays about my experience with Clinical Pastoral Education published in The Journal of Pastoral Care and Counseling. I consider it a major honor and am made bold. So I'm going to publish the essays I've written on this blog and then assemble them for a blook on Lulu.com. Eventually, I hope they'll find their way to other people going through the experience, which is meant to be a major initiation into the life of ministry and certainly is at LEAST that. But on the other hand, the hospital was at least in the Mid-West.

If you're close enough to a major library or hospital library that might carry this journal, it is pretty gripping to reat -- at least if you can handle some theology. Like animal control officers and fire or medical emergency responders, the stories really pile up and they are always surprising.

Anyway, I've got a lot things to post on my other blogs (especially scriverart.blogspot.com) which means that I'm a little short of time.

If you're close enough to a major library or hospital library that might carry this journal, it is pretty gripping to reat -- at least if you can handle some theology. Like animal control officers and fire or medical emergency responders, the stories really pile up and they are always surprising.

Anyway, I've got a lot things to post on my other blogs (especially scriverart.blogspot.com) which means that I'm a little short of time.

CHAPLAINCY

Chaplaincy, especially formal Clinical Pastoral Education, is a creature of institutions. I have no institution now. But I have a history with institutions and will reflect a bit on that. My formal beginner’s Clinical Pastoral Education was done in a large midwestern regional hospital. At that point I was in the midst of a four-year course of study at Meadville/Lombard Theological School wrapped around a Master of Arts in Religious Studies at the Divinity School of the University of Chicago. All of this means written contractual standards, agreements, emoluments and so on, including theologies. A structure of daunting complexity and subtlety.

I was forty years old. I had survived a tumultuous marriage to a sculptor (white but entwined religiously with tribal people), a decade of teaching on the Blackfeet Reservation, and five years as an animal control officer. I’d faced massacre, abandonment, intimacy, sex, drugs, death and rock ‘n roll in a rough-and-ready way with little training. (One of my major contributions at animal control was developing the first primitive beginnings of training for AC officers who worked alongside the Portland Police.) I’d been suicidal, murderous, despairing and exalted -- not always on Christian terms, mostly an iconoclast.

My denominational identification was with the Unitarian Universalist Association. I suppose it still is, though I was dropped from fellowship at my request in 1988 and belong to no congregation now. UU theology is mostly defined by some general principles and an amorphous response to the specific situation.

One of my major issues was authority -- who has authority? On what is authority based? Is hierarchy effective? What if it’s corrupt? Is authority a matter of being effective? What is the authority of “The Book,” and dogma? The jewels in the crown of CPE are the stories of the people. I have no need to disguise their names, because I can’t remember the names, but I can’t remove some characteristics because that would destroy the point. They are my touchstones when I think about these issues.

In the first story, I was called to help an Hispanic woman whose baby had died inside her. Labor-inducing drugs (very unpleasant) had been given to her and in part my job was holding a bowl while she vomited into it. She had been brought in by Mercy Flight and had no relative with her. I have never been pregnant but I’m comfortable with Indians/Indios and so she was in the position of teaching me all about what was happening.

This was maybe her twelfth pregnancy, though she was about thirty. She had lost some of them. She drank quite a bit. She felt that this baby had died, not because of the drinking, but because God was angry that all her children had different fathers -- the men had come and gone without marriage. She confided that her last baby had lived but had been a monster: what she described was severe fetal alcohol syndrome, but she didn’t seem to know that’s what it was. She said she was glad the baby was a boy because his face was badly mismatched -- the two sides had not grown together properly. Because he was so “ugly” she had been afraid of becoming pregnant again and asked her priest about birth control. No. She could hardly feed the babies she had, but no.

She was pregnant again too soon and her doctor said she should have an abortion, but again the priest said no. She was very worried about what this dead baby would look like. It turned out to be a perfectly formed (on the outside) girl. The nurses, who didn’t have much use for the mother, were full of pity for the baby. The mother was given a card with a photo of the baby and a footprint. One nurse suggested baptising the baby.

This was a time period when the Catholic Church was trying to authenticate and renew their Sacraments, especially since the media had managed to convince so many people of the efficacy of baptism, practically raising people from the dead. Baptism is a sacrament for living people to indicate their determination or the support of their religious community in living a Christian life. It is meant to wash away sins and signal a new beginning. A dead baby cannot be baptised because there is no beginning at all, no need for forgiveness or washing away of sin since even dead pre-natal babies were immersed in the sacred water of amniotic fluid (okay?) until delivery. I had a Catholic girlfriend in childhood (she’s still a friend) and we spent many a summer afternoon on the front steps debating these issues and passing judgment on such arrangements as “limbo.” At that point in seminary I had no formal training about Catholic theology.

The mother became fixated on getting this baby baptised. I called her priest: no. By now the mother’s family (at least the females) had arrived and were taking care of her. I was worried about coming between this woman and her priest because I knew she was getting much needed money from him. Anyway, we were being taught to abide by the patient’s theology rather than our own. I’d have been happy to bless, to dedicate, or whatever, but the mother specified baptism.

By this time the head nurse, a good Catholic, had become emotionally involved and ripped into me. I was forcing that poor baby to stand outside on the cold marble steps of the Pearly Gates rather than opening them up with baptism! To her, this metaphor was quite real. Catholic dogma allows believing Catholics to perform as priests in the absence of any consecrated person, so in the end the nurse solved the problem by simply baptising the baby herself. The patient and her family, who had brought along an elaborate christening dress for the dead baby, were very pleased.

Just before the patient left for home, I visited to say goodbye. She beckoned me in close so she could whisper and show me an envelope in her pillowcase stuffed with money. “Baptism gifts!” she explained. “Enough money to get my tubes tied. The priest -- he don’t need to know.”

This nicely literary story must be put with another. An old Italian man died. He’d been hovering for weeks and had received the Mass for the Ill several times. Again, the Catholics were trying to guide people to this ceremony and away from Extreme Unction, which the media had made into such a melodramatic plot element that everyone felt the need for it. But the ancient wife of this old man wasn’t going to get into any dogmatic debates. She wanted her priest there and she wanted her husband to have Extreme Unction and that was all there was to it.

I went to the phone and called the local priest. It was late at night and the phone rang a long time. The priest sounded very old and clearly had been awakened. I was aware that there was a shortage of priests, that the ones serving were very old, and I felt sorry. But my duty was to the old woman. I told him that Mr. So and So had passed away and that his wife was begging for Extreme Unction. “Well, if he’s already dead, I’ll come over in the morning and bless the corpse.”

I thought quickly. “Oh, Father!” I said, “Here comes the nurse. It’s a miracle. The old man has roused and he’s calling for you!”

A silence, then reluctantly. “All right. I’m coming.”

I went to stand by the elevator to intercept the priest, who luckily dressed like a priest, so I could say, “Oh, I’m so sorry, Father! He’s slipped away again. I’ll walk you to the room.”

I got away with outwitting dogma that time, as had the Mexican woman with the dead baby, but how much of that can a chaplain do without being defined as out of control?

Priests, ministers, chaplains, and other religious leaders are supposed to be held to a higher ethical and moral standard than society at large and therefore they are allowed freedoms and exemptions beyond other people. Greater authority, not based on much beyond the capacity to make careful, conscientious, emotional decisions that might not be approved if known by society at large. These people are trained and vouched for by their own chosen institution, which in this case bowed to the wisdom of Clinical Pastoral Education. Our UU Director of ministry told me CPE was about the ONLY accurate reading they could get on the quality and stamina of ministers-to-be.

Most of the time chaplains in the hospital, I found, were expected to persuade people to conform, “be nice,” and obey medical personnel. To step outside those bounds, like a cop stepping outside the legal rules of arrest and restraint, is to risk the loss of everything, one’s justification for being, one’s employment.

Yet I found it a constant temptation to go outside the rules, to throw over the constraints. Once I was called to deal with a man who was “angry at God.” They said he was shouting and railing because his wife was to have surgery for cancer. They were keeping her away from him, but he was ranting and slamming things in a conference room. He said he hated God and God was evil. I was called because “you’re a Unitarian and you won’t mind the way he talks.”

So here was this big guy, crying, wailing and cursing. He said he was an evil man, a man who cheated on his wife, was mean to her and everyone else, and so on. God’s revenge was to force all this terrible suffering and probably death on his wife. And he pounded his head on the table. He wanted me to pray for God to have mercy on him.

So I went risky and contentious, too. It looked to me as though he were determined to stay the center of attention, very sorry for himself. Taking a brisk tone, I said, “This is what your God is like? He tortures the innocent? I’d just dump a God as stupid as that.” I figured if he wanted a human vengeful god, I could label Him, too. “I’d just refuse to have anything to do with Him. Get a REAL God!”

The man stopped short and stared at me. All the crying and storming evaporated. He started back up. I just looked at him.

Then he really stopped. “You aren’t a proper chaplain,” he said in a hard voice. “I want a real chaplain. Chaplains are supposed to be comforters.”

“Sorry,” I said. “I’m the only chaplain available at the moment.” He got up and stalked out, clear out of the building evidently. I never saw him again and I never heard about the woman.

Now, wasn’t I just doing what he was doing? Making a convenient little idol out of a great theological concept? Yes. I’d say so. Wicked? Well, I restored order in the ward.

The last story is about a doctor from that very hospital, a much-loved big Alpha doctor, an effective administrator, who was now dying -- probably only had a few days to go but was conscious. The two senior chaplains had known him, worked with him, loved and depended on him for decades. He was telling them that he had absolutely no faith, that he might just as well be buried in a shoebox in the backyard with no ceremony, like a cat. Nothing he had done meant anything. It was all a farce. The CHAPLAINS were weeping.

So they sent me in, on the principle that nothing would do any good anyway. I made my best pitch, he was unimpressed, but he sort of patted me on top of the head and said, “Nice try, little girl.” I came out whipped and frustrated. It has taken me until now to understand that I did provide something for him: another underling to dominate. Power: even flat on his back in bed, no one could tell him anything.

So what does it all mean? What I get out of it is that it’s better to do something. At least you’ll have something to learn from. I didn’t tell all of this stuff to my CPE group. I’m not telling YOU about my worst debacles -- mercifully I don’t remember much about them anymore except that I’ve never felt so powerless and abandoned in my life. I learned it was possible to live through it all, until it’s my turn to die.

Unitarians have an emblem: a flame in a chalice, which they enjoy interpreting in many ways. Since I have experience with bronze casting, I use the figure of molten metal in a crucible. The crucible must be equal to the task of containing the molten metal. A crucible of cold metal is of no use. A crucible that is overwhelmed by the molten metal is a killer. An institution contains -- well, the Spirit, I guess. If the institution is too rigid or shallow, it cannot hold the Spirit or might even quench it. If the institution is well matched to the fire within it, it is a protection and guide.

What is my institution? Or should the question be what’s my chalice? I have no desire to sign on as a hospital or prison chaplain. But don’t I need a context to be a chaplain in any community? Or can I just be an old retired woman in a small Montana village and still occasionally flare up?

I was forty years old. I had survived a tumultuous marriage to a sculptor (white but entwined religiously with tribal people), a decade of teaching on the Blackfeet Reservation, and five years as an animal control officer. I’d faced massacre, abandonment, intimacy, sex, drugs, death and rock ‘n roll in a rough-and-ready way with little training. (One of my major contributions at animal control was developing the first primitive beginnings of training for AC officers who worked alongside the Portland Police.) I’d been suicidal, murderous, despairing and exalted -- not always on Christian terms, mostly an iconoclast.

My denominational identification was with the Unitarian Universalist Association. I suppose it still is, though I was dropped from fellowship at my request in 1988 and belong to no congregation now. UU theology is mostly defined by some general principles and an amorphous response to the specific situation.

One of my major issues was authority -- who has authority? On what is authority based? Is hierarchy effective? What if it’s corrupt? Is authority a matter of being effective? What is the authority of “The Book,” and dogma? The jewels in the crown of CPE are the stories of the people. I have no need to disguise their names, because I can’t remember the names, but I can’t remove some characteristics because that would destroy the point. They are my touchstones when I think about these issues.

In the first story, I was called to help an Hispanic woman whose baby had died inside her. Labor-inducing drugs (very unpleasant) had been given to her and in part my job was holding a bowl while she vomited into it. She had been brought in by Mercy Flight and had no relative with her. I have never been pregnant but I’m comfortable with Indians/Indios and so she was in the position of teaching me all about what was happening.

This was maybe her twelfth pregnancy, though she was about thirty. She had lost some of them. She drank quite a bit. She felt that this baby had died, not because of the drinking, but because God was angry that all her children had different fathers -- the men had come and gone without marriage. She confided that her last baby had lived but had been a monster: what she described was severe fetal alcohol syndrome, but she didn’t seem to know that’s what it was. She said she was glad the baby was a boy because his face was badly mismatched -- the two sides had not grown together properly. Because he was so “ugly” she had been afraid of becoming pregnant again and asked her priest about birth control. No. She could hardly feed the babies she had, but no.

She was pregnant again too soon and her doctor said she should have an abortion, but again the priest said no. She was very worried about what this dead baby would look like. It turned out to be a perfectly formed (on the outside) girl. The nurses, who didn’t have much use for the mother, were full of pity for the baby. The mother was given a card with a photo of the baby and a footprint. One nurse suggested baptising the baby.

This was a time period when the Catholic Church was trying to authenticate and renew their Sacraments, especially since the media had managed to convince so many people of the efficacy of baptism, practically raising people from the dead. Baptism is a sacrament for living people to indicate their determination or the support of their religious community in living a Christian life. It is meant to wash away sins and signal a new beginning. A dead baby cannot be baptised because there is no beginning at all, no need for forgiveness or washing away of sin since even dead pre-natal babies were immersed in the sacred water of amniotic fluid (okay?) until delivery. I had a Catholic girlfriend in childhood (she’s still a friend) and we spent many a summer afternoon on the front steps debating these issues and passing judgment on such arrangements as “limbo.” At that point in seminary I had no formal training about Catholic theology.

The mother became fixated on getting this baby baptised. I called her priest: no. By now the mother’s family (at least the females) had arrived and were taking care of her. I was worried about coming between this woman and her priest because I knew she was getting much needed money from him. Anyway, we were being taught to abide by the patient’s theology rather than our own. I’d have been happy to bless, to dedicate, or whatever, but the mother specified baptism.

By this time the head nurse, a good Catholic, had become emotionally involved and ripped into me. I was forcing that poor baby to stand outside on the cold marble steps of the Pearly Gates rather than opening them up with baptism! To her, this metaphor was quite real. Catholic dogma allows believing Catholics to perform as priests in the absence of any consecrated person, so in the end the nurse solved the problem by simply baptising the baby herself. The patient and her family, who had brought along an elaborate christening dress for the dead baby, were very pleased.

Just before the patient left for home, I visited to say goodbye. She beckoned me in close so she could whisper and show me an envelope in her pillowcase stuffed with money. “Baptism gifts!” she explained. “Enough money to get my tubes tied. The priest -- he don’t need to know.”

This nicely literary story must be put with another. An old Italian man died. He’d been hovering for weeks and had received the Mass for the Ill several times. Again, the Catholics were trying to guide people to this ceremony and away from Extreme Unction, which the media had made into such a melodramatic plot element that everyone felt the need for it. But the ancient wife of this old man wasn’t going to get into any dogmatic debates. She wanted her priest there and she wanted her husband to have Extreme Unction and that was all there was to it.

I went to the phone and called the local priest. It was late at night and the phone rang a long time. The priest sounded very old and clearly had been awakened. I was aware that there was a shortage of priests, that the ones serving were very old, and I felt sorry. But my duty was to the old woman. I told him that Mr. So and So had passed away and that his wife was begging for Extreme Unction. “Well, if he’s already dead, I’ll come over in the morning and bless the corpse.”

I thought quickly. “Oh, Father!” I said, “Here comes the nurse. It’s a miracle. The old man has roused and he’s calling for you!”

A silence, then reluctantly. “All right. I’m coming.”

I went to stand by the elevator to intercept the priest, who luckily dressed like a priest, so I could say, “Oh, I’m so sorry, Father! He’s slipped away again. I’ll walk you to the room.”

I got away with outwitting dogma that time, as had the Mexican woman with the dead baby, but how much of that can a chaplain do without being defined as out of control?

Priests, ministers, chaplains, and other religious leaders are supposed to be held to a higher ethical and moral standard than society at large and therefore they are allowed freedoms and exemptions beyond other people. Greater authority, not based on much beyond the capacity to make careful, conscientious, emotional decisions that might not be approved if known by society at large. These people are trained and vouched for by their own chosen institution, which in this case bowed to the wisdom of Clinical Pastoral Education. Our UU Director of ministry told me CPE was about the ONLY accurate reading they could get on the quality and stamina of ministers-to-be.

Most of the time chaplains in the hospital, I found, were expected to persuade people to conform, “be nice,” and obey medical personnel. To step outside those bounds, like a cop stepping outside the legal rules of arrest and restraint, is to risk the loss of everything, one’s justification for being, one’s employment.

Yet I found it a constant temptation to go outside the rules, to throw over the constraints. Once I was called to deal with a man who was “angry at God.” They said he was shouting and railing because his wife was to have surgery for cancer. They were keeping her away from him, but he was ranting and slamming things in a conference room. He said he hated God and God was evil. I was called because “you’re a Unitarian and you won’t mind the way he talks.”

So here was this big guy, crying, wailing and cursing. He said he was an evil man, a man who cheated on his wife, was mean to her and everyone else, and so on. God’s revenge was to force all this terrible suffering and probably death on his wife. And he pounded his head on the table. He wanted me to pray for God to have mercy on him.

So I went risky and contentious, too. It looked to me as though he were determined to stay the center of attention, very sorry for himself. Taking a brisk tone, I said, “This is what your God is like? He tortures the innocent? I’d just dump a God as stupid as that.” I figured if he wanted a human vengeful god, I could label Him, too. “I’d just refuse to have anything to do with Him. Get a REAL God!”

The man stopped short and stared at me. All the crying and storming evaporated. He started back up. I just looked at him.

Then he really stopped. “You aren’t a proper chaplain,” he said in a hard voice. “I want a real chaplain. Chaplains are supposed to be comforters.”

“Sorry,” I said. “I’m the only chaplain available at the moment.” He got up and stalked out, clear out of the building evidently. I never saw him again and I never heard about the woman.

Now, wasn’t I just doing what he was doing? Making a convenient little idol out of a great theological concept? Yes. I’d say so. Wicked? Well, I restored order in the ward.

The last story is about a doctor from that very hospital, a much-loved big Alpha doctor, an effective administrator, who was now dying -- probably only had a few days to go but was conscious. The two senior chaplains had known him, worked with him, loved and depended on him for decades. He was telling them that he had absolutely no faith, that he might just as well be buried in a shoebox in the backyard with no ceremony, like a cat. Nothing he had done meant anything. It was all a farce. The CHAPLAINS were weeping.

So they sent me in, on the principle that nothing would do any good anyway. I made my best pitch, he was unimpressed, but he sort of patted me on top of the head and said, “Nice try, little girl.” I came out whipped and frustrated. It has taken me until now to understand that I did provide something for him: another underling to dominate. Power: even flat on his back in bed, no one could tell him anything.

So what does it all mean? What I get out of it is that it’s better to do something. At least you’ll have something to learn from. I didn’t tell all of this stuff to my CPE group. I’m not telling YOU about my worst debacles -- mercifully I don’t remember much about them anymore except that I’ve never felt so powerless and abandoned in my life. I learned it was possible to live through it all, until it’s my turn to die.

Unitarians have an emblem: a flame in a chalice, which they enjoy interpreting in many ways. Since I have experience with bronze casting, I use the figure of molten metal in a crucible. The crucible must be equal to the task of containing the molten metal. A crucible of cold metal is of no use. A crucible that is overwhelmed by the molten metal is a killer. An institution contains -- well, the Spirit, I guess. If the institution is too rigid or shallow, it cannot hold the Spirit or might even quench it. If the institution is well matched to the fire within it, it is a protection and guide.

What is my institution? Or should the question be what’s my chalice? I have no desire to sign on as a hospital or prison chaplain. But don’t I need a context to be a chaplain in any community? Or can I just be an old retired woman in a small Montana village and still occasionally flare up?

Friday, January 26, 2007

HORSES THEY RODE by Sid Gustafson

1. Brakeman: The ride with the realbear

2. The Horse Medicine Man: Drinking with Bubbles

3. Outdoorsmen: Browning alley drinking

4. Red Man: Jesse James takes them to the ranch

5. Journeymen: Mabel and recovery

6. Studman: Rip, racehorses, and the son, Paddy

7. Grassman: Riding with Paddy

8. Other Men: Continental drift

9. Woman: Gretchen and cows

10. Wolfman: The wolf who drank with the cows

11. Lady’s Man: Making love

12. Ranch Man: Rip the boss

13. Lineman: Struck by lightning

14. Hiwayman: Driving to Spokane

15. Marathon Man: The race track

16. Legman: Doc the adulterer

17. Gentleman: Dealing with Willow

18. Newman: Wisdom from Bo

19. Milkman: Trish

20. Hiwayman: Homebound

21. Mystery Man: Nan comes aboard

22. Fireman: Back at the ranch

23. Middleman: Between wolf and dog, living in Palookaville

24. Gambling Man: Horserace

25. Mountain Man: Calling from summit

26. Weatherman: Rain and waiting

27. Horsemen: The race

28. Earthman: Burying Bubbles

29. Man: The Horse Medicine Bundle

Above is a list of the chapter titles of “Horses They Rode” by Sid Gustafson. It is immediately clear that this book is about what it is to be a MAN. It is also clear, even on the surface, that this is a Montana book. Sid grew up not far from where I’m living in Valier, the publisher is in Montana, the story happens mostly in Montana, and much of it is about Blackfeet, whom Sid can describe gracefully and honestly. So what is it REALLY about? I’d say it was about what it takes to be a mensch in a modern world that presses competition, toughness, ownership and emotional isolation as the measure of men. The final message is that real men are about nurturing: caring for those around them whether people, animals or grass. A natural conclusion for an author who is a veterinarian and a father.

One of the blurb reviews (by Neil McMahon) says that when he first began to read he was “taken aback, then disturbed.” After fifty pages he was drawn in and “humbled.” I had the same reaction, probably because the first chapter was written as a short story (much like Judy Blunt’s “Breaking Clean,” first chapter) and then the novel grew out of it. The first chapter is a picaresque, an exploit, a rather unlikely tale about a guy who jumps a freight out of Spokane in order to get back to the Blackfeet Rez and who is joined by a grizzly craving wheat residue in his boxcar. They don’t ship wheat in boxcars. Still, the grizzly, which in Blackfeet language is called a “real bear” in the same way that buffalo are “real meat,” acts like an actual bear.

The hero acts like 007 and climbs to the top of the train, then works his way back intending to get into the caboose, but this is after they stopped towing cabooses. There’s just a little digitized blinking box. The bear is “she” and Wendell’s reaction is to pray to the Virgin Mary. This discussion of “real men” is going to include relationships to the fe-male. And his daughter, rather than a lover or mother, is the key. But in the second chapter, Wendell is drinking at the Browning depot with an old Indian friend, so this is going to include red-men as well. But the Indian is not the key -- it’s the six-year-old daughter who brings the real delight and the son who brings the moral measure in that twelve-year-old straightforward way.

The plot is simple and the ending is pretty predictable, but Sid’s telling of the story, once he’s on the way, is extraordinary, laced with poetry and mythology, geology and anthropology. He’s as comfortable with image as with science. What he does NOT do is agonize over psychology. He’s hurting, he comes home, home is a place where everyone nurtures and heals each other, he finds his children, and he buries his good friend, a final kind of nurturing -- imperfect as things can be. Simple.

The language is extraordinary: lumpy, sometimes puzzling, grammar every which way, vernacular and poetry blurring into each other, medical terms when needed, fancy references (St. Wendell is the patron saint of wanderers and wolves.) It’s the sort of writing that makes some people sniff that it ought to have had a good editor -- and other people laugh that proper editing would ruin it! Sid is an original. (Montana NEEDS originals! Our supply is low.)

Nevertheless, since I’ve been in this country (off and on) almost as long as Sid’s been alive, and happen to know his family sort of from a distance, he came by all this stuff honestly, genetically and through nurturing. His sibs are equally extraordinary because the parents are larger-the-life, Vikings, massive and extravagant, and yet benign, inclusive. They don’t crush everything around them as some people in Montana certainly try to do.

But neither are the people in this book easily captured. The crushers want insurance, ownership, a sure thing. Sid’s book outlines an intimacy that is tolerant, allowing people to stay individual, keep their boundaries, make their own decisions. He’s willing to take chances. A real man meets his obligations but it appears that they center mostly on fatherhood, not good old dependable, chained-up husbandhood. There’s no husbandman on this list of chapters. Maybe he’ll explain in the next book. Sign me up in advance.

One of the key things that struck me is that though the main character is a veterinarian, there’s almost nothing here about drugs or surgery. (Sid’s practice emphasises natural medicine.) Healing is “hands-on,” rubbing, feeling, smoothing, connecting. When I was doing my hospital chaplaincy, a woman was dying. One of her symptoms was aching legs. Her husband stood by the bed hour-after-hour, patiently rubbing her legs which she said helped more than any medicine. It was about love. So is this book.

2. The Horse Medicine Man: Drinking with Bubbles

3. Outdoorsmen: Browning alley drinking

4. Red Man: Jesse James takes them to the ranch

5. Journeymen: Mabel and recovery

6. Studman: Rip, racehorses, and the son, Paddy

7. Grassman: Riding with Paddy

8. Other Men: Continental drift

9. Woman: Gretchen and cows

10. Wolfman: The wolf who drank with the cows

11. Lady’s Man: Making love

12. Ranch Man: Rip the boss

13. Lineman: Struck by lightning

14. Hiwayman: Driving to Spokane

15. Marathon Man: The race track

16. Legman: Doc the adulterer

17. Gentleman: Dealing with Willow

18. Newman: Wisdom from Bo

19. Milkman: Trish

20. Hiwayman: Homebound

21. Mystery Man: Nan comes aboard

22. Fireman: Back at the ranch

23. Middleman: Between wolf and dog, living in Palookaville

24. Gambling Man: Horserace

25. Mountain Man: Calling from summit

26. Weatherman: Rain and waiting

27. Horsemen: The race

28. Earthman: Burying Bubbles

29. Man: The Horse Medicine Bundle

Above is a list of the chapter titles of “Horses They Rode” by Sid Gustafson. It is immediately clear that this book is about what it is to be a MAN. It is also clear, even on the surface, that this is a Montana book. Sid grew up not far from where I’m living in Valier, the publisher is in Montana, the story happens mostly in Montana, and much of it is about Blackfeet, whom Sid can describe gracefully and honestly. So what is it REALLY about? I’d say it was about what it takes to be a mensch in a modern world that presses competition, toughness, ownership and emotional isolation as the measure of men. The final message is that real men are about nurturing: caring for those around them whether people, animals or grass. A natural conclusion for an author who is a veterinarian and a father.

One of the blurb reviews (by Neil McMahon) says that when he first began to read he was “taken aback, then disturbed.” After fifty pages he was drawn in and “humbled.” I had the same reaction, probably because the first chapter was written as a short story (much like Judy Blunt’s “Breaking Clean,” first chapter) and then the novel grew out of it. The first chapter is a picaresque, an exploit, a rather unlikely tale about a guy who jumps a freight out of Spokane in order to get back to the Blackfeet Rez and who is joined by a grizzly craving wheat residue in his boxcar. They don’t ship wheat in boxcars. Still, the grizzly, which in Blackfeet language is called a “real bear” in the same way that buffalo are “real meat,” acts like an actual bear.

The hero acts like 007 and climbs to the top of the train, then works his way back intending to get into the caboose, but this is after they stopped towing cabooses. There’s just a little digitized blinking box. The bear is “she” and Wendell’s reaction is to pray to the Virgin Mary. This discussion of “real men” is going to include relationships to the fe-male. And his daughter, rather than a lover or mother, is the key. But in the second chapter, Wendell is drinking at the Browning depot with an old Indian friend, so this is going to include red-men as well. But the Indian is not the key -- it’s the six-year-old daughter who brings the real delight and the son who brings the moral measure in that twelve-year-old straightforward way.

The plot is simple and the ending is pretty predictable, but Sid’s telling of the story, once he’s on the way, is extraordinary, laced with poetry and mythology, geology and anthropology. He’s as comfortable with image as with science. What he does NOT do is agonize over psychology. He’s hurting, he comes home, home is a place where everyone nurtures and heals each other, he finds his children, and he buries his good friend, a final kind of nurturing -- imperfect as things can be. Simple.

The language is extraordinary: lumpy, sometimes puzzling, grammar every which way, vernacular and poetry blurring into each other, medical terms when needed, fancy references (St. Wendell is the patron saint of wanderers and wolves.) It’s the sort of writing that makes some people sniff that it ought to have had a good editor -- and other people laugh that proper editing would ruin it! Sid is an original. (Montana NEEDS originals! Our supply is low.)

Nevertheless, since I’ve been in this country (off and on) almost as long as Sid’s been alive, and happen to know his family sort of from a distance, he came by all this stuff honestly, genetically and through nurturing. His sibs are equally extraordinary because the parents are larger-the-life, Vikings, massive and extravagant, and yet benign, inclusive. They don’t crush everything around them as some people in Montana certainly try to do.

But neither are the people in this book easily captured. The crushers want insurance, ownership, a sure thing. Sid’s book outlines an intimacy that is tolerant, allowing people to stay individual, keep their boundaries, make their own decisions. He’s willing to take chances. A real man meets his obligations but it appears that they center mostly on fatherhood, not good old dependable, chained-up husbandhood. There’s no husbandman on this list of chapters. Maybe he’ll explain in the next book. Sign me up in advance.

One of the key things that struck me is that though the main character is a veterinarian, there’s almost nothing here about drugs or surgery. (Sid’s practice emphasises natural medicine.) Healing is “hands-on,” rubbing, feeling, smoothing, connecting. When I was doing my hospital chaplaincy, a woman was dying. One of her symptoms was aching legs. Her husband stood by the bed hour-after-hour, patiently rubbing her legs which she said helped more than any medicine. It was about love. So is this book.

Wednesday, January 24, 2007

EXTREME ANIMAL CONTROL

Those of you who enjoyed the wilder stories of animal control days will be pleased to know that there is a growing circle of emergency medical response teams who blog and that they enjoy the same kind of exposure to the ridiculous and the deadly as animal control officers. If you start with “http://www.ambulancedriverfiles.blogspot.com,” you’ll find links to others and can lilypad your way through extraordinary tales told with pride, anguish and sometimes tongue in cheek.

I first came to this circle though stephenbodio.blogspot.com because of a story “ambulance driver” told about responding to a desperate call regarding an elderly couple living out in the country who had been attacked in a deadly way. When the EMTs arrived, the old people were on the ground

“I found myself kneeling on blood-soaked ground, tending an elderly woman who did not yet realize she was dead. Her husband already was, ripped from stem to stern like a victim from a slasher movie. I'll spare you the gory details, but suffice it to say that it appeared their assailant had wielded something like a cross between a machete and a potato masher. In dry medical prose, their injuries were Inconsistent With Life.”

He goes on to describe the assailant: an irate male ostrich. When I went to interview Los Angeles Animal Control, their Special Officer, a former Marine who had intended to mark time until a police position came open but got too fascinated to leave, told me that the animal they all feared the most was an ostrich. When the theory was proposed that birds were the last of the dinosaurs, all it took was one look at the work of an ostrich to deduce that the theory was absolute fact.

This whole ostrich story is amazing, though the EMT’s missed the main action when the deputy sheriffs were surrounded and advanced upon by the ostrich, which they shot. This technique won’t work in populated areas. The LAAC guy told me they finally located someone who could use bolas, those Argentinian three balls on strings, and he gave them some lessons plus his phone number. That’s LA: you can find any talent in that town. In fact, in the early days the animal control officers -- at least in the winter --tended to be rodeo cowboys looking for work in a warm climate.

Here’s a second animal control story that isn’t about formal AC officers.

Officers Use Taser to Free Tangled Deer

CANBY, Ore. - Confronted with a deer whose antlers were tangled in a rope swing at a rural home, two officers saw no good choices. They weren't about to try to free the animal themselves. It weighed several hundred pounds and was thrashing wildly. A bullet in the skull seemed the alternative.

"They thought they were going to have to kill it out of compassion," Lt. Jim Strovink of the Clackamas County sheriff's office said Wednesday. "It was going to die a slow, agonizing death."

Then Deputy Jeff Miller thought of the stun gun, commonly called a Taser, after its maker, used to immobilize out-of-control prisoners or suspects.

Zap!

The deer stopped moving. The officers, one a sheriff's deputy, the other a state trooper, untangled the rope, which was dangling from a tree limb, and freed the buck.

Not long after, the deer "took off happy as a clam," Strovink said. "That was pretty good thinking."

I’m on the list for National Animal Control Association inquiries about various techniques, equipment, and so on. The most common questions seem to be about tasers, pepper spray, and even guns. When I was an officer, we had to qualify on a rifle range, but we rarely used guns and never carried them except for some special reason. Didn’t carry spray and hadn’t heard of Tasers. In the city there was generally a police officer or deputy close enough to do any shooting necessary, but deadly force is no joke and even sprays and Tasers have the potential to turn into emergency EMT calls, maybe on behalf of the person wielding the spray or stun gun. Conditions need to be right -- the wind not blowing in one’s own face -- and one must be in total control. Anyway, there’s always the chance that when you use the Taser to stop a knothead, you might stop his or her heart forever.

Still, that worked pretty slick on the deer and it might work on an ostrich in case you’ve never had any bola lessons or don’t happen to be carrying bolas under your car seat.

The bottom line on these stories, to my mind, is that emergency responders need to be cooperators and quick thinkers, no matter what the problem is. One of Ambulance Driver’s latest posts is about an emergency in a strip club, where there was probably a lot more response than the emergency called for. I never did get a call to a strip club, but I did go pick up a dog at a massage parlor once. It was a little fluffy white poodle. The girl in the leopard print negligee told me they found it in the rain, all muddy and forlorn. The girl in the flame red babydolls said they gave it a nice bubble bath. And the girl in the black lace bra and panty set told me they blew it dry. There was a pause. Then we all laughed.

I’m not sure whether the dog was happy as a clam. I’ve always wondered how one knows when a clam is happy. When it’s escaped, I guess.

I first came to this circle though stephenbodio.blogspot.com because of a story “ambulance driver” told about responding to a desperate call regarding an elderly couple living out in the country who had been attacked in a deadly way. When the EMTs arrived, the old people were on the ground

“I found myself kneeling on blood-soaked ground, tending an elderly woman who did not yet realize she was dead. Her husband already was, ripped from stem to stern like a victim from a slasher movie. I'll spare you the gory details, but suffice it to say that it appeared their assailant had wielded something like a cross between a machete and a potato masher. In dry medical prose, their injuries were Inconsistent With Life.”

He goes on to describe the assailant: an irate male ostrich. When I went to interview Los Angeles Animal Control, their Special Officer, a former Marine who had intended to mark time until a police position came open but got too fascinated to leave, told me that the animal they all feared the most was an ostrich. When the theory was proposed that birds were the last of the dinosaurs, all it took was one look at the work of an ostrich to deduce that the theory was absolute fact.

This whole ostrich story is amazing, though the EMT’s missed the main action when the deputy sheriffs were surrounded and advanced upon by the ostrich, which they shot. This technique won’t work in populated areas. The LAAC guy told me they finally located someone who could use bolas, those Argentinian three balls on strings, and he gave them some lessons plus his phone number. That’s LA: you can find any talent in that town. In fact, in the early days the animal control officers -- at least in the winter --tended to be rodeo cowboys looking for work in a warm climate.

Here’s a second animal control story that isn’t about formal AC officers.

Officers Use Taser to Free Tangled Deer

CANBY, Ore. - Confronted with a deer whose antlers were tangled in a rope swing at a rural home, two officers saw no good choices. They weren't about to try to free the animal themselves. It weighed several hundred pounds and was thrashing wildly. A bullet in the skull seemed the alternative.

"They thought they were going to have to kill it out of compassion," Lt. Jim Strovink of the Clackamas County sheriff's office said Wednesday. "It was going to die a slow, agonizing death."

Then Deputy Jeff Miller thought of the stun gun, commonly called a Taser, after its maker, used to immobilize out-of-control prisoners or suspects.

Zap!

The deer stopped moving. The officers, one a sheriff's deputy, the other a state trooper, untangled the rope, which was dangling from a tree limb, and freed the buck.

Not long after, the deer "took off happy as a clam," Strovink said. "That was pretty good thinking."

I’m on the list for National Animal Control Association inquiries about various techniques, equipment, and so on. The most common questions seem to be about tasers, pepper spray, and even guns. When I was an officer, we had to qualify on a rifle range, but we rarely used guns and never carried them except for some special reason. Didn’t carry spray and hadn’t heard of Tasers. In the city there was generally a police officer or deputy close enough to do any shooting necessary, but deadly force is no joke and even sprays and Tasers have the potential to turn into emergency EMT calls, maybe on behalf of the person wielding the spray or stun gun. Conditions need to be right -- the wind not blowing in one’s own face -- and one must be in total control. Anyway, there’s always the chance that when you use the Taser to stop a knothead, you might stop his or her heart forever.

Still, that worked pretty slick on the deer and it might work on an ostrich in case you’ve never had any bola lessons or don’t happen to be carrying bolas under your car seat.

The bottom line on these stories, to my mind, is that emergency responders need to be cooperators and quick thinkers, no matter what the problem is. One of Ambulance Driver’s latest posts is about an emergency in a strip club, where there was probably a lot more response than the emergency called for. I never did get a call to a strip club, but I did go pick up a dog at a massage parlor once. It was a little fluffy white poodle. The girl in the leopard print negligee told me they found it in the rain, all muddy and forlorn. The girl in the flame red babydolls said they gave it a nice bubble bath. And the girl in the black lace bra and panty set told me they blew it dry. There was a pause. Then we all laughed.

I’m not sure whether the dog was happy as a clam. I’ve always wondered how one knows when a clam is happy. When it’s escaped, I guess.

Tuesday, January 23, 2007

IT'S BEGINNING TO COME TOGETHER

This morning the Great Falls Tribune ran a story about the Baker Massacre, which seems to have a new name every time I see a story about it. It is the Blackfeet version of 911 -- a mistaken cavalry attack on an innocent (in fact, desperately ill) camp where old folks, women and children (the only ones there since the men had gone hunting) were slaughtered in the snow. It was meant as a reprisal for an attack by a renegade.

When I went to get gas for my monthly provisioning loop up to Shelby, over to Cut Bank, and back, Heart Butte kids were chattering at the service station and a teacher reminded me that they were going to the annual commemoration on the actual spot of the massacre-- not in a bus but in cars. They’ve been doing this for several years now -- maybe a decade.

Back home, unpacked, fed and napped, I sat down to listen to Brian Kahn’s Yellowstone Public Radio program, “Home Ground.” The subject was Indian education. There were two guests: Carol Juneau, the state representative for the Blackfeet reservation and a school bureaucrat for thirty years -- not a teacher. Her expertise is in organizing programs and getting funding for them. She has a good reputation on the reservation and she’s a “separatist” in the way that Quebec is separatist in terms of Canada. That is, the answer is ALWAYS “put us in charge of our own affairs and give us more money.”

Here’s the problem: “Last year, Indian students were more than three times more likely to drop out of school than white students, with an 8.4 percent dropout rate compared to the 2.7 percent rate among whites, according to data gathered by the state Office of Public Instruction.”

“Dropout rates for Indians peaked in the 10th grade, but were not limited to upper grades. Among junior high students, for example, American Indians constituted 72 percent of the dropouts and were 12 times more likely to drop out than white classmates, the figures show.”

This is all Indians on all reservations. To put this in terms of my own experience, half the kids drop out as soon as they’re legally able (sixteen years old) and half of the remainder drop out before they finish high school. That’s the way it was in 1961 when I came, and that’s still the way it is.

“Studies show that on average, American Indian children begin to fall behind peer groups in Montana between the ages of 22 months and five years, reflecting a lack of emphasis on reading and learning in the household, said Chris Lohse, the OPI director of policy research.”

Chris Lohse, the OPI specialist and analyst, is a new voice. He does not address culture and all that, but goes directly to the poverty problem. (When clueless people used to say to Darrell Kipp, “Why are these people so poor?” he’d say, “They don’t have enough money.”) Chris sets out four criteria:

1. The place has concentrated poverty -- that is, the poor are crammed together.

2. The poverty is generational rather than situational -- it’s not a matter of temporary hard times but rather goes back and back.

3. The poor people are isolated in space, either across acres of prairie and timber or across many blocks of run-down housing. All they know about the rest of the world is from television.

4. The poverty is DEEP, defined as being less than fifty percent of the official federal poverty line and characteristic of at least a quarter of the population.

Says Chris, these four criteria are typical of inner city and also reservation schools. If one creates a category of schools that achieve at least 60% of the national levels of achievement, NO SCHOOL in any inner city or on any reservation will meet this measure. The fact that there are special federal grants for these schools doesn’t matter -- it is the individual households that count.

And this is circular: if the education achievement is low, the poverty is recreated, generation after generation. Expectations and morale sink lower and lower.

So here’s one of the more surprising things. Some reservations suddenly came upon money through casinoes. As soon as the average income level of households went up, the educational achievement also went right up. They are directly linked. No one has looked at this information in quite this way before. In short, education is an aspect of economics, pure and simple.

Brian Kahn has the idea that Indians are just like “immigrants” and ought to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. Chris says flatly that it’s not the same thing. If you look at immigrant groups who meet the four criteria above, even some Asian groups (Hmong, Samoan) show the same lack of achievement.

There are a few other elements here for Indians, mostly political, and this is where I stand with the separatists. The Indians didn’t come here to seek a new life -- they were invaded. They were destroyed, their country was seized and now even the land is being destroyed. For many years white people siphoned off any profits and many assets -- it still continues. The US Government has ripped off lease money and other assets from the very beginning, probably far in excess of money spent on the tribe.

How can they help but be resentful? It was as though they were innocent Iraqi families who just happened to be in the wrong place when the fire-spouting attack helicopters came and devastated their neighborhood. (The irony is that some of those US soldiers, a high proportion, are Indian because the military is one way to escape poverty and rack up a little self-esteem.) Their only power is a refusal to cooperate, whether in the classroom or in the larger world. Even corruption is defiance, subversion.

The Baker massacre was reprisal for Yellow Owl killing Malcolm Clarke who was married to the sister of Mountain Chief, Yellow Owl’s father. Regardless of how you argue over “who started it,” the fact is that it was originally a family quarrel. That revenge murder became the justification for wholesale massacre of more than a hundred people. Malcolm’s son rode with the Cavalry. Now think about the invasion of Iraq, which some believe is retaliation for Saddam Hussein’s attempt to kill George Bush’s father. Think about the massive poverty now in Iraq: the vineyards, aqueducts, olive groves, electrical plants and (yes) oil fields destroyed since we invaded. We think it’s their problem, but it’s not. WE pick up the bill, one way or another.

Bush’s administration has done its best to roll all the money into the CEO pockets, those guys being caught red-handed all over the country, guys (very few gals) who make 400 times what their employees make and evaporate the pension fund. The middle class is disappearing. In short, Bush (whom I admit is only a pawn and a symbol) is trying to make Indians of us all. We’d better smarten up!

Education means prosperity. Prosperity means education. My Social Security automatic deposit comes in the morning. They gave me a raise -- but then confiscated more than half of it for that prescription medicine boondoggle. I don’t feel any smarter, but I’m studying on it.

When I went to get gas for my monthly provisioning loop up to Shelby, over to Cut Bank, and back, Heart Butte kids were chattering at the service station and a teacher reminded me that they were going to the annual commemoration on the actual spot of the massacre-- not in a bus but in cars. They’ve been doing this for several years now -- maybe a decade.

Back home, unpacked, fed and napped, I sat down to listen to Brian Kahn’s Yellowstone Public Radio program, “Home Ground.” The subject was Indian education. There were two guests: Carol Juneau, the state representative for the Blackfeet reservation and a school bureaucrat for thirty years -- not a teacher. Her expertise is in organizing programs and getting funding for them. She has a good reputation on the reservation and she’s a “separatist” in the way that Quebec is separatist in terms of Canada. That is, the answer is ALWAYS “put us in charge of our own affairs and give us more money.”

Here’s the problem: “Last year, Indian students were more than three times more likely to drop out of school than white students, with an 8.4 percent dropout rate compared to the 2.7 percent rate among whites, according to data gathered by the state Office of Public Instruction.”

“Dropout rates for Indians peaked in the 10th grade, but were not limited to upper grades. Among junior high students, for example, American Indians constituted 72 percent of the dropouts and were 12 times more likely to drop out than white classmates, the figures show.”