In the 1950's our family made a pilgrimage to the old homestead. My father was quite nostalgic and thought that some of the tarpaper was "original," though when he was born there the interior was quite different and weather-tight.

This week my last biological aunt died, my father’s sister, the third child conceived and delivered but the second to survive in a little tar-paper covered shack near Faulkton, South Dakota. My father was the second to the oldest. The oldest came prematurely, my grandmother believed because she couldn’t resist the chance to go to town in the wagon. She knew the jolting would be bad for the pregnancy, but she so yearned for a little social life.

My grandfather, Sam Strachan, and my grandmother, Beulah Finney, had homesteaded next to each other in tiny shacks. When they married, they pulled the two little shacks together and ran a new strip of tarpaper around the connection. Once there was an earthquake, which tipped Beulah’s china cupboard over on its face and broke many of her beloved dishes. She didn’t say anything. She just went to the front door, sat on the threshold with her apron thrown over her head, and wept.

Once, early in the marriage, Sam took out Beulah’s team of horses instead of his own and found them sluggish -- spoiled. He gave them a cut with the buggy whip, which Beulah saw from the window. She stormed out. “Sam Strachan, you’ll not whip MY horses!” Two strong Scots personalities, both school teachers. In fact, Sam was the school superintendent for Faulkton County. Lifelong, their idea of a perfect gift was new spectacles, a fountain pen, or a book.

May Alice was the only girl among the four surviving children. Bruce, older, was a sturdy but bookish lad. May was full of mischief. Before the second pair were born, May and Bruce developed a tight relationship. Girls were supposed to have graces, so May learned the piano. Bruce spied on the lessons and practiced more than May did, so they both learned. Seth and Glenn would rather be outside, where they once started a prairie fire when trying to smoke a skunk out of a culvert. (What for, no one ever said.)

The family moved up to Swan River, Manitoba, to make a better living in new country. Just as they got there, an epidemic of equine encephalitis killed their horses. With no way to put in a crop, they lived on home-canned moose meat and credit. Sam went to work building highways, hard brush work. At one point the farm house they rented came with the owner’s unbargained-for invalid mother, whom they had to care for. Beulah broke down and one of the boys had to walk many miles to find and bring back Sam while May took care of both older women. The bank illegally foreclosed on the first potato crop as soon as they were harvested and in the railroad car, so Sam had to give pursuit.

Then they discovered the Kovar Krabgrass Kultivator and started a business. The machine came in pieces from the States and the family assembled, sold and delivered them. Pretty soon they were doing well enough to move to a house in Brandon. It would mean nothing to Yankees that the house had belonged to Martha Ostenso, author of “Wild Geese,” but Canadians might recognize the name.

In those years the nearly-grown children finished college in Winnipeg and May fell in love with Doc, her lifelong partner. (He was formally “Murdock,” the son of a prosperous and powerful farmer in Ontario.) At the same time, Elsie MacKinnon formed a close relationship with Glenn and the two couples became linked by a double wedding.

Today Elsie is still living in Santa Ana, California. It was hard on her to be separated from May and Doc, but Glenn had developed lung troubles so severe that the doctor said he had to move. May and Elsie stayed close through letters and phone calls, often from their pillows in the middle of the night. I wouldn’t be surprised to hear now that Elsie knew that May was gone and went with her. I can picture them walking off across the prairie together, maybe holding hands, until they are beyond the horizon and can’t be seen anymore.

The farm machinery business was destroyed by tariffs at the border, so Sam and Beulah built a little cabin on the truck and came out to Portland, OR, to see how it was. The whole family moved to Portland just as the Depression hit. Times were hard until WWII, when Portland became a ship-building hub. Doc’s drafting skills were valued and May worked as a receptionist for a doctor. She was glamorous and conscientious and wore a big cartwheel black straw hat.

The youngest brother, Seth, became a bomber and transport pilot and was also the pilot for VIP's, such as a load of newspaper and magazine editors that General Dwight Eisenhower sent to see the Nazi death camps because he accurately predicted that people would try to deny the Holocaust. After the war Seth was a pilot for TWA. His wife, Jo, had been a stewardess and raised their daughters and son beautifully.

May and Doc built a house in an outlier neighborhood of Portland that turned out to be quite upscale, though not on today’s terms. May’s taste was elegant: pale green with Oriental motifs, a little study all in red plaid, and a flamingo pink bath. Later she began to paint delicate scenery and birds. In his later years Doc learned to fly a small plane, but his real love was ice-skating, a Canadian pleasure in his youth, and he won prizes. They had two children, Jeannie and Scottie, a teacher and an engineer, and their lives were dependably safe and smooth from then on. In old age May became a bit reclusive, esp. after Doc died.

Down in Santa Ana, dislocated, Elsie struggled through a depression that was hard on her daughter, Diane, and emerged a poet. Glenn built a real estate business, but his son, Ross, became a grocery executive. Glenn and Elsie also lived peaceful lives, because after WWII people could. The economy was stable, people who took drugs or drank lived somewhere else, and pollution was not an issue. Progress was the name of the political game.

But May is free now and has gone back home where Sam and Beulah and Doc have been waiting for her. That’s as good a metaphor as any.

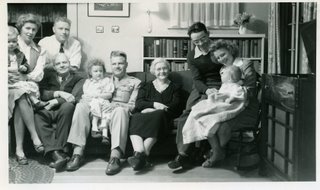

World War II days. Far to the right, May and Doc with their new baby, Jeannie.

Oh, may we all emerge from hardship as poets!

ReplyDeleteMary, I love that they lived in Martha Ostenso's house -- I once had coffee in the Starbucks below McClelland & Stewart in Toronto and almost swooned with the thought of how many of my admired Canadian authors may have done the same.

Funny how all us old pioneer families have such stories -- failed crops, dead stock, tarpaper shacks. And yet we survived. Some of us, even, as poets.

Thanks for writing down this history. I pray I'll never see the kind of hardship the homesteaders experienced, and if I do, I pray I'll have the strength they did.

ReplyDeleteFaulk County, South Dakota, is just slightly north of the area described in Land of the Burnt Thigh.

What an amazing lifespan your aunt May had, from a homestead to the technological marvels of the 21st century.

Thanks for telling about "Burnt Thigh," Genevieve! I didn't know there was a book like that so close to Faulkton. When they homesteaded there, the Indians had been driven out. But when Beulah was growing up in Michigan, she was traveling afoot with her mother along a path in the forest when they came to a bank of what must have been Cree-Chippewa. The Indians stood aside in a double row so the woman and girl could pass between them, heads up high and barely trembling with fear because it was so much like running a gauntlet. Beulah claimed that one of the men said, "Ugh, squaw heap brave!" But we know that was probably apocryphal.

ReplyDeleteI'll have to get hold of "Burnt Thigh."

Prairie Mary