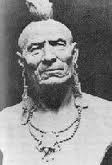

Geronimo

Geronimo is a man who won’t go into a box. He was not a “medicine man,” a glamorous warrior, a faithful Tonto, or a madman. He was a sensible, resourceful family man with nine, or maybe twelve, wives (one of them massacred alongside his mother in front of his eyes) and a lot of kids (some of them also massacred). He was said to hang his enemies in trees by their balls. He was a master of survival, even gunshot wounds, who was conquered but then rode in inaugural parades as though he had won, who dressed in a top hat and loincloth and made souvenir arrows to sell. Presidents drank from his exhumed skull as initiation to their spying club at Yale -- or thought they did. Maybe it was George Washington’s skull.

People on the North American continent will say, “Oh, I’ve never met an Indian because I’ve never visited a reservation,” but the truth is that no matter where they are there’s probably an Indian no more than ten miles away. Let’s settle one thing: Tim Barrus is a descendant of original Delaware Indians (Lenape) who spoke a version of Algonquian. His life weaves in and out of Chippewa in Michigan, Cherokee in Carolina, Navajo in Arizona, and Seminole in Florida. So do ours, but we don’t realize it. Because we think about “tribes” as though they were boxes. You probably don’t know the difference between Algonquian and Athabascan. Neither did I, but I looked it up. They cover two halves of North America with large, complex, allied groups. Navajo is a subset of Athabascan.

Delaware

There are two things that make this book different from the last: Tim’s father had died (as he says, alcoholic, diabetic, blind, foot amputated) calling for Tim, and the son would have gone to him except that he had just had a double hip replacement, which meant fighting through opioid withdrawal because of the necessary pain killers. A photo shows him so gaunt he’s nearly unrecognizable. Then there was a pulmonary embolism that left him brain-high from hypoxia and fever.

The people of this continent speak French, Spanish, all sorts of folk dialects and class vernaculars and that’s the way this book is, too. “Voice” is one of the recurring themes. This writer is often speaking something between James Joyce and some contemporary rapper, though he doesn’t much use crime or black ghetto talk -- never the “f” word unless he really means “fuck.”

It’s poetry, dark as restaurant dishwater: “when you had to slip the skin of your hands into that industrial-strength soap and the cold and horrid water was enough to make your eyeballs turn black.” [p. 176)

Then bright as afternoon: “The butterflies that late summer were already yellow and dined on ditch sunflowers that grew parched along the dirt roads of the arroyos time and time again.”

On the next page, bits of borrowed poetry: “Sometimes hath the brightest day a cloud, and after summer evermore succeeds barren winter, with his wrathful nipping cold. So care and joy abound as seasons fleet.” (Shakespeare)

Next paragraph echoes: “Sings warm songs of socks around my brother’s pink and stupid feet.” The brother had stolen a plastic sack of socks and the manager, instead of arresting him, brought the boys a whole box of new socks. They were so grateful; it was so rare.

The writing is a tapestry. Hillbilly locutions, out West phrases, bar banter, self-conscious suburban talk -- all over-embroidered with sarcasms, reversals, exaggerations and sequins of flashing beauty. It is “memoir” in a kind of molecular sense, recollections of a drugged man whose brain operating system has always been a little askew (hearing voices, reading upside down) and whose idea of narrative order is simply traveling, with a lot of doubling-back, like Geronimo losing the cavalry.

But this isn’t Jack Kerouac or even Burroughs, though Barrus values both. The voice that comes through for me is Sam Shepard who had the same kind of angry, alcoholic Ulster man for a father. He stays at a (slightly) better class of motel is all. Here’s Shepard in an essay called “Williams, Arizona”: “He’s staring at the sun-faded color blowup of the Grand Canyon mounted above the TV in a cheap frame. The picture’s warped. The wall it hangs on is phony pink adobe. Actually, it’s sheetrock with pink crud smeared on it like curdled Pepto-Bismol.” He’s there to finish looping a film “he cares nothing about anymore and can’t remember why he wanted to do it in the first place.”

Consider a story Tim tells, which might or might not have happened to him, but is a vivid metaphor set in his recurring trope of carnival. A carnival shooting gallery provides a gun with a slightly bent barrel. The father, knowing this, stands behind his innocent son with a revolver and times his bullets so that every time the boy pulls the trigger, he coincides to shatter a wooden duck. Amazed and elated, the son accepts the prize, a child-sized stuffed bear. (Is a carny going to argue with a man packing a gun?) The two boys love the big squashy thing and put it in bed between them. That night the father comes home drunk and shoots the bear in the chest . A story told deadpan, never discussed.

The wanderjahr continues along the old webwork of paths that Eisenhower had just ordered transformed into highways. They steal a Corvette (this is a Route 66 story) and a girl joins them. They eat in pancake houses, which function like home kitchens with an impatient waitress for a mom as they linger on their elbows, playing with their cigarettes, amusing the truckers. “As far as we were concerned, we could sleep anywhere. The ground. but when you add the female element into the situation, everything changes. We would need motel rooms. Especially in light of all the glorious and pervervitated sex we might have with Ronnie Spectacular.”

Ronnie was old enough to check into motels, which the boys were not, and she had a driver’s license, which the boys did not. She liked to play mom: “No popcorn fights, no wrestling on the furniture -- it’s paid for, no stealing the TV, no cheese pizzas, no liquor, and no dogs at the Starlight Motel in Hemphill, Texas.” (Shepard might have stayed there.) I made a list of all the specific towns mentioned in this book. It’s a page long and all the towns are real. I looked them up.

Tim describes delivering a calf at a rodeo because he often helps veterinarians. (This is the West -- you take help as you can get it.) His arm is in the cow and feeling the calf. Ronnie sings to the cow because Gene Autry and Roy Rogers do this. “It felt like we were standing right next to an amazing waterfall, pristine, clear, my arm is in the waterfall of songs. A nice thundering. I stop thinking about what I am doing -- I let the thing do itself. Simply guide the waterfall down the slope it wants to go. Seeing in the Navajo way. And tracing paths. Negotiating a soft place at the edge of the meadow is what I ought to know.” He feels how to help and it works. If it bothers you to think “Navajo,” substitute “Zen” or “Tao.” Anything but the Ulster man’s rage and force. We’re with Yoda now.

Tim had won the Poets and Writers “Beyond Margins” prize and his address, written in doggerel couplets, machine-guns publishing. In those days (only ten years ago) writers had contracts with publishers, which put them into indentured servitude as publicity hacks, going where they were told to go, giving speeches that obeyed a list of things not to say. Even if no one attended, which was often the case.

James Joyce

Life magazine and high school English teachers had taught everyone that writing was a grand and potent blaze that could change the world. The publishers just wanted to sell and that meant not offending, but always titillating. Publishers were no longer educated gentry with elbow patches on their tweed jackets, but instead soup company CEO profit pimps. This book was the fulfillment of a contract or it would have been too honest to publish. Geronimo making real arrows to sell to tourists. Writers are all “pretty women” waiting for Richard Gere to come along and fulfill their dreams. It won’t happen. And yet, this book tells the truth.

Across the street from us when I was growing up lived two women: one was a beautiful Filipina who had been grievously damaged in a car crash sustained while driving her sports car too fast on the way to meet her rich famous lover. She now lived in chronic pain, nursed by a brisk, butch sort of woman partner. When they reached a certain age, they bought an Airstream trailer and left for Florida, a very American thing to do. Geronimo would have understood it completely: no one is more American than Geronimo. Except maybe the determination to capture Geronimo and exploit him, even if it kills him. It’s archetypal. Bone deep.

Tim Barrus and Navajo at the grave of Geronimo at Fort Sill, OK.

The tree is full of honor offerings: cloth and Indian Health Service spectacles.

No comments:

Post a Comment