What’s remarkable is that the magic holds. Here I am at 67, cloistered in Montana. On Christmas Eve I watch this subtle, many-layered movie. (The truth is that when I was twelve I hadn’t the least idea what was going on some of the time because there are stories within stories and people turn into other people or maybe gods.) It begins with Divali, the Festival of Lights when a lot of tiny oil lamps are set burning, many floating on the water. This festival comes earlier on the calendar than Christmas, but it has much of the same significance: birth coming out of darkness, family going on, numinous mystery that shines through the ordinary.

The archetypal mother and father of the story are classical English actors, married offstage. The Indian nurse, Nan, is also classic, as is the Irishman next door -- a man we’ve seen many times in movies, most often as a priest but this time as the Un-theist philosopher. There are three adolescent daughters from different families. Two are redheads: Harriet who writes poetry and is no swan (that was me) and Victoria who is smashingly beautiful with a great shawl of stunning red hair. The third girl is the Irishman’s daughter, a half-Indian girl (who seems completely Indian to us) who illustrates the part of the story that is about India. It is she who is transformed through the movie again and again in art and fancy. In my childhood, the girl across the street looked very much like her, though she was Philippina, and had that kind of mysterious aura. In fact, that was her name: Aura May. I still think of her as the girl in this movie, adding my own layer.

Then there is the one-legged man. Are we aware that, aside from being a classically wounded man who can’t really run away from these girls and a subject for many jokes (check Google), the “one legged man” like “the three legged man” and the “one eyed man” are euphemisms for sex? (Referring to the male member. The father is also one-eyed.) Well, nevermind. The girls hardly know what is going on themselves. Nor did I when I first saw the movie.

There’s a whole brood of children. One dies, one is born. The one-legged man asks, “What can we do?” The half-Indian girl, educated in a Western-style convent, says, “Consent.” Yes. Well, she IS half-Irish, too. She could say, “Yes,” like Mollie Bloom. All three girls want to say yes, but they quarrel with Fate. As the gorgeous rich girl protests, “I don’t want to be real! I want to stay in the garden!” Fat chance. Harriet, who considers a kiss on the forehead to be fulfillment, tries to bypass the guilts and trials of family by going straight to death, but the river won’t let her die. It's not time yet.

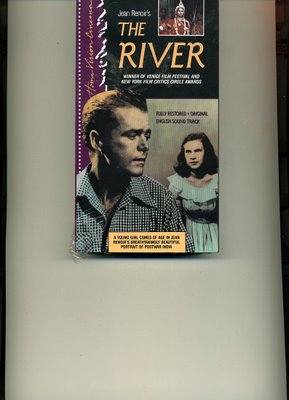

This movie somehow overwhelmed all the careful Presbyterianism in my mother’s church. This movie is my true religion, which is why I watch it now instead of “Miracle on 34th Street” or some such. I haven’t got the fancy Criterion DVD, which I WILL get someday. Rather I have the old videotape. Even that took a while to find, partly because there are so many movies called “The River.” So many small things date to that movie. I began to go barefoot, which my mother thought was the result of a trip to California. I looked for a little cubbyhole to write in, like Harriet’s, but didn’t find one.

Late in life, my mother refused to see any movies she had really loved earlier, for fear they would have gone cheesy and tinny -- spoiled by time. She wanted them to be remembered gardens she didn’t have to leave. I couldn’t even persuade her to see the most recent version of “Little Women,” though it’s the one I love the best and I feel confident she would have loved it as well. She and her sisters came close to living it. We went to see the Alcott house which WAS in the movie!

I’ve taken the opposite attitude. In college I took World Religions so I could learn more about Divali. I’m sure I ended up here with Blackfeet Indians because there wasn’t much hope of getting to India. (Sorta like Columbus.) I went to Divinity School as a way of consent. I see that the acting in this film is a little amateur and that several of the actors never had another part in a movie. They were being themselves more than they were acting. But I don’t CARE. At the time I read as many Rumer Godden books as I could lay hands on, and then read both of Jon’s books. (That’s her sister.) None of the discussions or speculations or competitions could ever disturb that first glamour. And now I find that they examine British cultural assumptions in a useful way. Ideas -- so much of my own reality is ideas.

My parents had hinted that there was something special about the movie, so in 1951 -- it HAD to be at the Guild Theatre, the little Portland art-house theatre -- when the movie came onto the screen with hands painting white designs onto a floor and a voice-over explaining, I thought I was watching a documentary. We went to lots of them. I sometimes say my father’s true religion was geography.

At first when the real story started, I was aware of my parents watching me. They sentimentalized the whole thing about little girls who write poetry and are dreamy about boys and are growing up, yah-da, yah-da, yah-da. Victorian ideas they used to relieve anxiety in a non-threatening way. I think they were scared spitless by it all. (Quite rightly. Consider what we know happens to girls these days! Probably did then, too, but we didn't know about it.) Adolescence had been a bad time for my mother. Then the whole movie just came into me (dare I say “penetrated?”) and was part of me from then on. I didn’t mind that sometimes Harriet seemed almost crazy or that the one-legged man wasn’t particularly special.

That’s the power of truth in story, of a sensuous culture that accepts suffering, of ancient philosophies that might or might not be called “religion.” The Festival of Lights. Seems like there are more lights around Valier than usual this year.

No comments:

Post a Comment