The grocery stores around here are beginning to sell off their “summer bowls” for fifty cents or so. They only sold for a dollar in the first place. I’m talking about those pressed-plastic big mixing-sized bowls that are so handy for potato salad or ears of corn on picnics or at a big harvest table. They’re good for gathering bulky stuff from the garden -- carrots or squash -- and then good for the discarded pods or peelings when you carry them out to the compost. I use them to scrub or sort or snap or strip.

Most of them are round, imitations of the real mixing bowls of earthenware thrown on a wheel. When I really mix something like bread, I use a Pyrex bowl but in the past I’ve used stainless steel “spun” bowls that don’t break. Of course, the choice antique ones are wooden. I have one so big that it was hard to store, so I drilled a hole in the edge and hung it from a thong, Indian-style.

The ones I liked the best so far were distributed a couple of years ago: the clear ones tinted green and imprinted with fantasy lettuce leaves. I have a favorite one that is smooth but clear, tinted green, but it’s getting so many cracks in it that it’s not really even good for popcorn. The point of these bowls is for them to be so inexpensive that they can be discarded with no grief, but I get attached to the objects I use.

Some of this summer’s bowls are relatively shallow and have a pouring lip on one edge. I suppose they are more for liquids or maybe even for changing the oil in a car -- they’re about that size. I keep one full of water in my driveway and animals of many sorts come to drink, but mostly Crackers who seems to be marginally diabetic. This leads to the occasional cat/spat with Casper, the white cat with gray ears from across the street who is bigger and meaner and thinks he owns this whole end of town. There is almost always a “daddy-long-legs” drowned in the bottom of the bowl. One. Only one.

When I see photos of starving Africans, I see that the last possession many of them have -- after even the tattered t-shirts have disintegrated -- is a cheap bright plastic bowl or jug. Hunter/gatherer equipment, even when the food is relief rice arriving in sacks. More than ten thousand years ago it would have been a calabash gourd or maybe the stomach of an animal, blown up like a balloon so it dried hollow. I don’t see metal bowls -- maybe too heavy, maybe too hot, but one could cook in them. Maybe there is no fuel for cooking anyway, or maybe the mother is holding onto the metal pot.

They sell "summer tumblers" too and this year's was tall ones, clear with incised circles and double-walled for insulation. Last summer's were short, clear, intense blue or green with soft hobnail-type bumps on them so that they have a fascinating nubbly quality.

In the Fifties when aluminum was still new, cottage cheese came in aluminum tumbers colored metallic blue, green, rose. We collected enough for the family and used them at the supper table with the plates my mother had “hunter-gathered” on our trips across the US. Each plate was out of the same mold but commemorated a different state. I was surprised to see reproductions of these tumblers show up in that “Yankee” catalog of disappeared candy and original-formula Vicks. There must be nostalgia for them. In summer they were great for cold drinks.

Maybe years from now I’ll think of this summer and orange, yellow or bright green plastic bowls will pop into my head. There are always color-coded and related place-setting dishes to go with these bowls but I only buy the bowls. I have the idea that I might go to casting plaster and they would be perfect for that since they’re slick and flexible enough to crack the left-over plaster out afterwards. The amount they would hold would be just about right for a small bust or figure. When I think of the Scriver studio, one of the strong sense memories is the enameled washbowls we used for mixing plaster. The shallow white bowls with a red rim and a hole for hanging out on the porch by the pump.

Summer bowls are almost like eggshells: useful -- even arguably vital -- and yet ephemeral material culture, cheerful expendables like the foods they carry. The one on my kitchen counter right now has been collecting used coffee filters with the grounds still in them. When it’s full, I’ll tear up the filters and dump them along with the grounds in my flower beds where the alkali reading is a little too high. Good mulch. And I’ll enjoy swinging the empty bowl on the way back into the house.

Wednesday, August 30, 2006

Two Quite Different Stories

The call came in just as I was beginning to think about where to have lunch -- like someplace where no dogs were hanging around -- when the call came on the radio to go to a high school where a dog was biting kids. In my experience biting dogs on school grounds are almost always gone by the time I get there, but off I went. The student body was at lunch and milling around on the sidewalks, even in the street. The problem was not a biting dog but a boy who wanted his dog to bite.

This young man was siccing his dog on people he didn’t like for some reason, but the dog was much more peaceful than the boy and a little confused by all the excitement. I went to the dog and took it by the collar. The boy went for my throat and began to strangle me. Another boy held me from behind. I would not let go of the collar. Kids were crowded all around and I knew that if I fell or collapsed, I would be kicked -- hard. An administrator was hanging out a second story window yelling, “You let that woman go! Do you hear me?” Pretty typical administration.

Finally the collar broke, the bell rang, and the crowd dispersed. The kids had tried to open my truck, ALWAYS locked -- if the dogs I’d already picked up had been turned loose in a different part of town than they knew, the chances of them finding their way home were slim, despite all the media stories about dogs with internal GPS monitors who cross the country to find their families. Frustrated by the lock on the canopy door, the students had opened the hood and torn out the sparkplug wiring.

When all the kids were gone, an administrator appeared and took me inside for a cup of coffee -- my neck was red and scraped and my throat was sore -- and to soothe me so I wouldn’t sue the school. In the meantime the AC officer from the next district over arrived, found the wires and connected my sparkplugs so the truck would run. When I got back to the shelter for debriefing, I was informed that I could press charges against the kid or not (he was a known person) -- it was up to me. I pressed charges.

By this time I’d also been told some stories. One was about kids at this same school one winter day with a rare snowfall. They were throwing snowballs at passing cars, realized that some snowballs were hard enough (mostly ice) to make dents, and began to make snowballs that included rocks. A big expensive black car passed them rather slowly. They put some good dings in the glossy paint. Out stepped one of Portland’s more notorious pimps, who slid a knife into the closest kid, wiped the blood off on the kid’s jacket, and left. No one pressed charges against him. The kid survived. No administrator saw or heard anything.

When we got to the juvenile hearing, there was a panel rather than a judge but the kid and his dad were there. The kid’s file, about a foot thick, was on the table. The panel really didn’t know what to do with the situation, which I imagine was tame compare to some of the other stuff in the file. It was clear that they didn’t like “dog catchers.” My school teacher side was at war with my officer side was at war with my author side. The boy was given probation of some kind.

Several weeks later I saw the dog loose on the street. It went into the truck so quickly its ears were flying and I began to pull out into traffic when the boy flung himself on the hood, pounding the windshield as hard as he could. Grateful he had no hard object at hand, I just kept pulling away, praying equally that the windshield would hold and that the boy wouldn’t slide off the hood into traffic. I was lucky or my prayers were answered.

This time it was “real” court because the boy and the dog were both considered wards of the adult, the reponsible party. Fines and fees imposed were the maximum allowed, several hundred dollars when a license and room and board were included, and the judge provided a stiff lecture. I had a feeling that the father gave his son a good beating that night. Again, officer argued with teacher argued with author. No wonder the kid sicced his dog on other kids. But at least the father had recovered the dog for him. I stayed pretty much out of that part of town for a while.

A quite different call came in about an old lady being menaced by a possum. Old folks called animal control quite a lot, partly because they had real complaints but also partly because no one else ever came to see them. Frail little old ladies, curled and shortened by age, would grab the front of my shirt to hoist themselves up enough that they could tip their bifocals back and see my face. “Officer, honey, you’ve got to help me!”

This old lady explained that her pomeranian, Goldie, ate her food out on the porch but a possum kept coming to eat it and threatened Goldie. (Goldie, a little puff of a dog with a tongue sticking out in the middle, danced and flirted everytime she heard her name.) The old lady herself had tried to take the broom to the possum but it hissed and showed a mouth like a barracuda, crowded with sharp teeth.

At this time in Portland there was possums everywhere. I picked half a dozen of them up dead in the streets every morning. They fitted into the ecology of leafy Portland very well, eating slugs and candy bar wrappers indiscriminately, and curling up to sleep all day in the many crevices and pockets around and under older houses. The good news was that they were not aggressive, mostly meddled around at night, and didn’t carry rabies. I used to explain that rabies is a brain disease and that possums don’t have enough brains to catch rabies. Truly, they are an ancient form of mammal, almost pre-mammal, and have a different enough chemistry not to be vulnerable to that particular virus. Later, as often happens with overpopulations, something that could infect them or some predator wiped them away, to be replaced by raccoons who are a lot more trouble and DO carry rabies.

I gave the little old lady the talk about not leaving food out and the importance of closing up any good lurking and napping spots. I left her a live trap and instructed a neighborhood boy scout about how it worked, how to open it if Goldie got in there, what to use for bait, and what to do if the possum got in -- call immediately.

It was a day or so before anything happened and then I got an emergency call -- the possum is caught! Go right away!

The possum wasn’t in the trap. It had showed up while the little old lady and Goldie were out planting bulbs in the yard and the possum had made a feint at Goldie. The little old lady, full of adrenaline and determined to save her pom, had thrown her spading fork overhand and with Frank Buck accuracy had managed to get one tine on each side of the rascal’s head, pinning it to the ground with no damage. Now the possum, looking disgusted, was in a stanchion like a cow ready to milk except that its “hands” were each gripping a tine of the fork. Then it had occurred to the old lady that it was a warm day and the possum was pinned in full sun, so she’d taken the lid off her garbage can and propped it to be a kind of awning. And she’d provided a pan of water.

This time I was struggling with a mix of amazement and amusement as I praised the little old lady. She was very proud. I took the possum by the tail -- they can’t curl up when they’re full grown so one can safely pack them along like a handbag -- and lowered it into the live trap for transport to the shelter. I felt as though I ought to have a medal or certificate for the old lady, but her fantasy was that Goldie had held off the invader long enough for her to act. Goldie pranced and twirled around with her eyes bugging out. It was an exciting morning for all concerned.

This young man was siccing his dog on people he didn’t like for some reason, but the dog was much more peaceful than the boy and a little confused by all the excitement. I went to the dog and took it by the collar. The boy went for my throat and began to strangle me. Another boy held me from behind. I would not let go of the collar. Kids were crowded all around and I knew that if I fell or collapsed, I would be kicked -- hard. An administrator was hanging out a second story window yelling, “You let that woman go! Do you hear me?” Pretty typical administration.

Finally the collar broke, the bell rang, and the crowd dispersed. The kids had tried to open my truck, ALWAYS locked -- if the dogs I’d already picked up had been turned loose in a different part of town than they knew, the chances of them finding their way home were slim, despite all the media stories about dogs with internal GPS monitors who cross the country to find their families. Frustrated by the lock on the canopy door, the students had opened the hood and torn out the sparkplug wiring.

When all the kids were gone, an administrator appeared and took me inside for a cup of coffee -- my neck was red and scraped and my throat was sore -- and to soothe me so I wouldn’t sue the school. In the meantime the AC officer from the next district over arrived, found the wires and connected my sparkplugs so the truck would run. When I got back to the shelter for debriefing, I was informed that I could press charges against the kid or not (he was a known person) -- it was up to me. I pressed charges.

By this time I’d also been told some stories. One was about kids at this same school one winter day with a rare snowfall. They were throwing snowballs at passing cars, realized that some snowballs were hard enough (mostly ice) to make dents, and began to make snowballs that included rocks. A big expensive black car passed them rather slowly. They put some good dings in the glossy paint. Out stepped one of Portland’s more notorious pimps, who slid a knife into the closest kid, wiped the blood off on the kid’s jacket, and left. No one pressed charges against him. The kid survived. No administrator saw or heard anything.

When we got to the juvenile hearing, there was a panel rather than a judge but the kid and his dad were there. The kid’s file, about a foot thick, was on the table. The panel really didn’t know what to do with the situation, which I imagine was tame compare to some of the other stuff in the file. It was clear that they didn’t like “dog catchers.” My school teacher side was at war with my officer side was at war with my author side. The boy was given probation of some kind.

Several weeks later I saw the dog loose on the street. It went into the truck so quickly its ears were flying and I began to pull out into traffic when the boy flung himself on the hood, pounding the windshield as hard as he could. Grateful he had no hard object at hand, I just kept pulling away, praying equally that the windshield would hold and that the boy wouldn’t slide off the hood into traffic. I was lucky or my prayers were answered.

This time it was “real” court because the boy and the dog were both considered wards of the adult, the reponsible party. Fines and fees imposed were the maximum allowed, several hundred dollars when a license and room and board were included, and the judge provided a stiff lecture. I had a feeling that the father gave his son a good beating that night. Again, officer argued with teacher argued with author. No wonder the kid sicced his dog on other kids. But at least the father had recovered the dog for him. I stayed pretty much out of that part of town for a while.

A quite different call came in about an old lady being menaced by a possum. Old folks called animal control quite a lot, partly because they had real complaints but also partly because no one else ever came to see them. Frail little old ladies, curled and shortened by age, would grab the front of my shirt to hoist themselves up enough that they could tip their bifocals back and see my face. “Officer, honey, you’ve got to help me!”

This old lady explained that her pomeranian, Goldie, ate her food out on the porch but a possum kept coming to eat it and threatened Goldie. (Goldie, a little puff of a dog with a tongue sticking out in the middle, danced and flirted everytime she heard her name.) The old lady herself had tried to take the broom to the possum but it hissed and showed a mouth like a barracuda, crowded with sharp teeth.

At this time in Portland there was possums everywhere. I picked half a dozen of them up dead in the streets every morning. They fitted into the ecology of leafy Portland very well, eating slugs and candy bar wrappers indiscriminately, and curling up to sleep all day in the many crevices and pockets around and under older houses. The good news was that they were not aggressive, mostly meddled around at night, and didn’t carry rabies. I used to explain that rabies is a brain disease and that possums don’t have enough brains to catch rabies. Truly, they are an ancient form of mammal, almost pre-mammal, and have a different enough chemistry not to be vulnerable to that particular virus. Later, as often happens with overpopulations, something that could infect them or some predator wiped them away, to be replaced by raccoons who are a lot more trouble and DO carry rabies.

I gave the little old lady the talk about not leaving food out and the importance of closing up any good lurking and napping spots. I left her a live trap and instructed a neighborhood boy scout about how it worked, how to open it if Goldie got in there, what to use for bait, and what to do if the possum got in -- call immediately.

It was a day or so before anything happened and then I got an emergency call -- the possum is caught! Go right away!

The possum wasn’t in the trap. It had showed up while the little old lady and Goldie were out planting bulbs in the yard and the possum had made a feint at Goldie. The little old lady, full of adrenaline and determined to save her pom, had thrown her spading fork overhand and with Frank Buck accuracy had managed to get one tine on each side of the rascal’s head, pinning it to the ground with no damage. Now the possum, looking disgusted, was in a stanchion like a cow ready to milk except that its “hands” were each gripping a tine of the fork. Then it had occurred to the old lady that it was a warm day and the possum was pinned in full sun, so she’d taken the lid off her garbage can and propped it to be a kind of awning. And she’d provided a pan of water.

This time I was struggling with a mix of amazement and amusement as I praised the little old lady. She was very proud. I took the possum by the tail -- they can’t curl up when they’re full grown so one can safely pack them along like a handbag -- and lowered it into the live trap for transport to the shelter. I felt as though I ought to have a medal or certificate for the old lady, but her fantasy was that Goldie had held off the invader long enough for her to act. Goldie pranced and twirled around with her eyes bugging out. It was an exciting morning for all concerned.

Monday, August 28, 2006

Animal Control and the Law

I’m no lawyer but I can think of more than a half-dozen “kinds” of law, all of which might involve animals:

1. Felony offenses like murder, and major robberies, which all of us understand as law. (Dogs have been repeatedly defined as “deadly weapons” when used to rob or otherwise attack people. People have been held under manslaughter laws when allowing or urging their animals to kill.)

2. Misdemeanor offenses like driving laws which are understood by people, though they might disagree. (Seatbelts for humans, restraints for dogs in the back of pickups.)

3. Regulations which are written into administrator’s handbooks and contain many definitions. (What is a leash? What is “own?” What are the fees for impoundment, licenses, offenses? How should horses who are used for horse-drawn carriages on the city streets be regulated?)

4. Laws that rise up from the citizenry through referendums, like drunk driving laws. (No horses in town. Dog and/or cat licensing.)

5. Laws that refer to treaties, which may even transcend national law. (Migratory bird law, which is international and protects almost all birds.)

6. Natural laws that enforce themselves, like falling off a log.

Thesis: the whole culture has a great preoccupation with laws, probably from trying to get some kind of consensus about events that are seen in radically different ways by different parts of the citizenry. The traditional transition problems between country and city are now joined by difficult transitions through immigration. People who have finally given up on keeping goats in town are now treated to the sight of a live goat being killed, butchered and barbecued in the yard of their neighbors.

This puts major emphasis on consequences and the sorting out in court that happens AFTER troublesome incidents. Some of the laws also require an army of enforcers creating a sea of paper and a certain amount of snitching on the part of citizens, instead of the exertion of peer pressure. And it preoccupies another large body of people who sit around trying to imagine contingencies and think up rules against them, always limited by the experiences of the thinkers.

People do what they do because of habit, conventional behavior and peer pressure, assumptions about how things work, convenience, negligence. Probably this side of things needs more work, which means getting out on the street and talking to people. Animal control officers rarely think of this as part of their duties, but it would be very helpful if they did. Even less than wildlife wardens, animal control officers are not trained to think in terms of ecologies, the interlinking of minor forces that can converge to create a big problem. For instance, increasing density of pups -- immature litters -- can be tinder for a distemper plague that burns through many pets and what I’d like to call “interstitial animals” -- that is, animals that live in the offal-rich spaces of inhabited places. Raccoons, possoms, rats, squirrels, crows, and so on. Maybe a coyote or two.

No one wants to take responsibility for these unowned animals -- except that a lot of people like to feed them, which adds to the problem and which is a cultural force. Feeding birds is considered a generosity and a delight. Trying to make people stop feeding birds is pretty hard, as bear specialists will tell you. Even along wilderness areas where bears will SURELY be attracted to a bird feeder or an apple tree, people persist in having bird feeders and apple trees. They are Good Thing, as Martha Stewart would say.

Jurisdictions are a big part of the law -- when is a problem an animal control problem? In urban environments, animal control managers will try to limit jurisdiction to owned animals (well, and those in the same species as common pets, even if they are feral) while pushing responsibility over to the wildlife people (usually state as opposed to city or county AC) for the “interstitials.” The argument is that they have the proper expertise and equipment. And anyway, pet control is funded by licensing but no one buys a possom license.

On the hand, people do have a disconcerting way of making raccoon, skunks and so on into pets. There used to be a big mean boar raccoon who belonged to a family in my district. I must have quarantined it for biting people (mostly kids trying to be friendly) at least three times. (The animal had shots, but no one knows whether rabies shots work to make raccoons immune to rabies. Raccoons are exceptionally susceptible to rabies, which is killed by sunlight, because the animals are nocturnal.) Finally the law was changed to include that raccoon in laws meant for dogs, and it was ordered out of town.

We also had a long episode, promoted by the media, resulting from a New Year’s Eve reveler who met a skunk on the sidewalk in the wee smalls and tried to pet it. The skunk bit him. He had to have the rabies shots himself before I could find that skunk. There were a lot of jokes about “pink skunks.” At last I found the family who owned the skunk, but they swore they never let it out -- always shut it into the basement at night. A quick perambulation of the house revealed a hole in the foundation with skunk tracks going in and out. The skunk was the usual black and white.

Speaking of rabies, gateway laws (like those regarding boarding airline passengers) have helped to keep England rabies-free and the US rabies-scarce. But a man who brought his son and a found dog home from Mexico in a small personal airplace, inadvertently brought rabies with him. The dog was incubating the virus and bit the son, who was one of the first people to survive because he ended up in the Oregon Health Sciences University where he was put on massive life support until his brain could recover. (More later.) The bill was astronomical and the insurer probably didn’t have to pay it, because the dog was brought into the country illegally.

The point is that even if the perfect laws are passed, unless the knowledge of “why” is out there in society, unless the mechanisms for triggering inspection and forced compliance are funded, unless the laws are clear and boundaries real, then bad stuff still happens. And there is no way to legislate that people should stop being stupid.

1. Felony offenses like murder, and major robberies, which all of us understand as law. (Dogs have been repeatedly defined as “deadly weapons” when used to rob or otherwise attack people. People have been held under manslaughter laws when allowing or urging their animals to kill.)

2. Misdemeanor offenses like driving laws which are understood by people, though they might disagree. (Seatbelts for humans, restraints for dogs in the back of pickups.)

3. Regulations which are written into administrator’s handbooks and contain many definitions. (What is a leash? What is “own?” What are the fees for impoundment, licenses, offenses? How should horses who are used for horse-drawn carriages on the city streets be regulated?)

4. Laws that rise up from the citizenry through referendums, like drunk driving laws. (No horses in town. Dog and/or cat licensing.)

5. Laws that refer to treaties, which may even transcend national law. (Migratory bird law, which is international and protects almost all birds.)

6. Natural laws that enforce themselves, like falling off a log.

Thesis: the whole culture has a great preoccupation with laws, probably from trying to get some kind of consensus about events that are seen in radically different ways by different parts of the citizenry. The traditional transition problems between country and city are now joined by difficult transitions through immigration. People who have finally given up on keeping goats in town are now treated to the sight of a live goat being killed, butchered and barbecued in the yard of their neighbors.

This puts major emphasis on consequences and the sorting out in court that happens AFTER troublesome incidents. Some of the laws also require an army of enforcers creating a sea of paper and a certain amount of snitching on the part of citizens, instead of the exertion of peer pressure. And it preoccupies another large body of people who sit around trying to imagine contingencies and think up rules against them, always limited by the experiences of the thinkers.

People do what they do because of habit, conventional behavior and peer pressure, assumptions about how things work, convenience, negligence. Probably this side of things needs more work, which means getting out on the street and talking to people. Animal control officers rarely think of this as part of their duties, but it would be very helpful if they did. Even less than wildlife wardens, animal control officers are not trained to think in terms of ecologies, the interlinking of minor forces that can converge to create a big problem. For instance, increasing density of pups -- immature litters -- can be tinder for a distemper plague that burns through many pets and what I’d like to call “interstitial animals” -- that is, animals that live in the offal-rich spaces of inhabited places. Raccoons, possoms, rats, squirrels, crows, and so on. Maybe a coyote or two.

No one wants to take responsibility for these unowned animals -- except that a lot of people like to feed them, which adds to the problem and which is a cultural force. Feeding birds is considered a generosity and a delight. Trying to make people stop feeding birds is pretty hard, as bear specialists will tell you. Even along wilderness areas where bears will SURELY be attracted to a bird feeder or an apple tree, people persist in having bird feeders and apple trees. They are Good Thing, as Martha Stewart would say.

Jurisdictions are a big part of the law -- when is a problem an animal control problem? In urban environments, animal control managers will try to limit jurisdiction to owned animals (well, and those in the same species as common pets, even if they are feral) while pushing responsibility over to the wildlife people (usually state as opposed to city or county AC) for the “interstitials.” The argument is that they have the proper expertise and equipment. And anyway, pet control is funded by licensing but no one buys a possom license.

On the hand, people do have a disconcerting way of making raccoon, skunks and so on into pets. There used to be a big mean boar raccoon who belonged to a family in my district. I must have quarantined it for biting people (mostly kids trying to be friendly) at least three times. (The animal had shots, but no one knows whether rabies shots work to make raccoons immune to rabies. Raccoons are exceptionally susceptible to rabies, which is killed by sunlight, because the animals are nocturnal.) Finally the law was changed to include that raccoon in laws meant for dogs, and it was ordered out of town.

We also had a long episode, promoted by the media, resulting from a New Year’s Eve reveler who met a skunk on the sidewalk in the wee smalls and tried to pet it. The skunk bit him. He had to have the rabies shots himself before I could find that skunk. There were a lot of jokes about “pink skunks.” At last I found the family who owned the skunk, but they swore they never let it out -- always shut it into the basement at night. A quick perambulation of the house revealed a hole in the foundation with skunk tracks going in and out. The skunk was the usual black and white.

Speaking of rabies, gateway laws (like those regarding boarding airline passengers) have helped to keep England rabies-free and the US rabies-scarce. But a man who brought his son and a found dog home from Mexico in a small personal airplace, inadvertently brought rabies with him. The dog was incubating the virus and bit the son, who was one of the first people to survive because he ended up in the Oregon Health Sciences University where he was put on massive life support until his brain could recover. (More later.) The bill was astronomical and the insurer probably didn’t have to pay it, because the dog was brought into the country illegally.

The point is that even if the perfect laws are passed, unless the knowledge of “why” is out there in society, unless the mechanisms for triggering inspection and forced compliance are funded, unless the laws are clear and boundaries real, then bad stuff still happens. And there is no way to legislate that people should stop being stupid.

Saturday, August 26, 2006

Animal Control and Veterinarians

The first time I encountered a veterinarian in my role as an animal control officer was not pleasant. Responding to an injured dog call, I found a little wire-haired terrier with a concussion, unconscious in the gutter. Since at that point I had no ties to veterinarians, I just went to the closest one, who turned out to despise animal control. With the limp dog on his stainless steel table top between us, he sneered, “This dog with die unless it has immediate intervention but I’m not going to do anything unless I am assured that I’m going to be paid.” He meant it.

I called Animal Control where Burgwin said, “The county will pay for basic emergency care but then you must bring it here to the shelter. The county will not pay for extensive care and if you authorize it, you will pay for it yourself.” This was the proper answer but not the moral or emotional one. Burgwin was relentless about turning an officer’s decisions back to the officer. With authority goes responsibility and decision-making, full on with consequences. The same as for military or for civilian police or -- come to look at it -- for doctors and veterinarians.

The dog was wearing a nice red harness with many tags attached. I called again, this time to find out the owner of the dog according to the most recent license. The owner didn’t answer the phone. I went back to the table where the dog had not stirred. The veterinarian had inserted an IV. We faced each other again. “I’m just keeping the animal alive while you decide what you’re going to do,” he said. “I can NOT afford to pay for every injured animal that comes in here!”

“But this is obviously a valued pet. We know who the owner is -- this is not an anonymous stray.”

His anger level went up. “People abandon their dear pets as soon as there’s a bill attached.” I suspect his practice was not doing well. Maybe his bedside manner.

I’d just moved to an apartment of my own and paid deposits and so on. Money was tight. Maybe he was right about the owner not appreciating his dog coming to the vet. None of my family ever took pets to the vet.

“Of course, what does animal control care? You people are so callous from killing hundreds of pets that you can hardly be expected to do anything. I’m surprised you brought this dog in here.”

I couldn’t hold out any longer. I slapped down my VISA. Then I left the dog there, now a private dog instead of an impound, and went to the address of the owner which proved to be a neat little brick house. I left a long note attached to the screen door. That evening, back at the shelter, the owner called with grateful thanks. The dog was still alive. She was paying the bill happily.

Burgwin didn’t criticize me for my decision. It was mine and I was lucky. He was happy for me that I was lucky.

Months later, in winter, I responded to an injured dog call that said a police officer was waiting. The dog was a black lab whose leg had been mangled by a car with studded tires. The officer had put the dog in the trunk of his squad car and stood by with the lid lifted, watching for me while guarding the dog from further injury. I thanked him -- he was almost in tears for the dog’s sake. The dog was stoic and grateful.

This time I had a developed friendship with Dr. Plamondon, founder of DOGS (Drinkers of Good Scotch) and one of the best veterinarians in town, much less my area, and since this was a good dog, wearing tags, I took the poor fellow to Dr. P. He didn’t ask any questions, just got to work sorting and sewing.

Dr. P. was a bit of a philosopher. We talked once about the appeal of animals and I compared cows to deer, with cows on the losing end. Dr. P. drew himself up and delivered an eloquent defense of the seductive beauty of the Brown Swiss Dairy Cow, entirely persuasive.

Once he told a very funny story at his own expense, about being in training with a prominent veterinarian when a customer rushed in the door early one morning and said, “Here’s my dog! Be sure you have him fixed by 5PM and I’ll pick him up after work.”

He was a very good dog, show quality, and Dr. P. wondered why the owner wanted him neutered, but he assumed the customer was always right and there must be circumstances he didn’t know, so he set to work right away. The dog would have the rest of the day to recover for the trip home.

But when the customer came back, he said, “Wait! His ears look just the same! Why didn’t you fix them?” He wanted them surgically altered to stick up, as is the custom with some breeds. (In England they don’t do that sort of thing anymore except to dock tails and dewclaws that would get torn or loaded with burrs in field dogs.) He was not happy to discover that a lot of stud fees had been surgically removed.

Dr. P. was a big man with hands to match, so somehow it was a little surprising -- but very endearing -- that his specialty was birds. One room was full of recycled premature baby isolettes for the recovery of exotic birds. I heard talk in there, stuck my head in, and saw macaws and parrots, all swearing and declaring and sometimes even singing bits of human songs. On another occasion I stuck my head in another door and discovered a springer spaniel joyfully having water therapy for his back in a bathtub full of hot water. His therapist was a rubber ducky.

It was wonderful to me, a happy privilege of my role, to be able to go in the back door of this veterinarian, as though I were part of the team. While Dr. P. worked on the black lab, I called the shelter to get the owner’s name and then called the owner. The owner said, “That dog is constantly getting into trouble and I’m tired of bailing him out. He can just take care of himself. I’m not paying any inflated bill from a tinhorn veterinarian. The dog can pay for himself. Maybe that will teach him.”

Dr. P.’s reaction was a bitter laugh. I drove over to the owner’s house and wrote him a ticket. He went to court to argue about it. I told the judge what had happened. He was ordered by the judge to pay the veterinarian bill as well as the highest fine possible. He didn’t get his dog back.

There was one veterinarian I learned to avoid -- all we female officers learned to avoid him -- because he always thought the animal should be “checked for ringworm” by carrying it into a small dark closet so he could shine an ultraviolet light on it and “accidentally” bump into the female officer’s front. Another was a crook who would put down foreign objects under the animal while taking an x-ray and claim that surgery was necessary to remove it. One of the services we provided to veterinarians was the removal of animals who had died or been euthanized, which was okay, but one veterinarian specialized in euthanizing slow greyhounds and sometimes there were a dozen of them, so many that there was no room for the live dogs in the truck. Burgwin ended that.

One of the veterinarians I enjoyed most -- maybe for the wrong reasons -- was an older divorced man who styled himself a feminist, and stocked “MS.” magazine in his waiting room. His staff seemed to be entirely pretty women under thirty, but that’s not unusual in a veterinary practice. Animals tend to attract “mommies.” (These days the women just go ahead and become veterinarians themselves.) Anyway, since he seemed open to sort of racy topics, I asked him a question for which I really wanted an answer.

Dogs in the throes of coition get stuck together -- “tied” in the jargon -- and I wanted to know how that happened. (For many observant young boys it’s a source of great worry -- until they find something worse when they run into the myths of the “vagina dentata” which bites off whatever is inserted, a myth so widespread that the Blackfeet have a story about Napi introducing a stone as a surrogate so as to break off all the teeth and make his partner a lot safer for him and his beloved parts.)

More important, I wanted to know how to get two dogs unstuck quickly so as to avoid the repeated debacle of the female running off, dragging her friend by a most inconvenient and painful appendage. Did throwing cold water on them really work? And whose fault was it anyway? Did the male swell up or did the female lock on?

A half-hour of diagrams and argument later, I was no wiser. It seems that the female dog has a sphincter just a bit inside the vagina entrance and this grabs during intercourse. But the male dog has a ring of flesh on his penis that swells up during intercourse. Both animals need to relax for these swellings and constrictions to ease. They are meant to stand there “tied” for a while to give the sperm some swimming travel time, which helps especially with dogs because there might be a serious size differential, unlike wolves or coyotes. The vet’s position was that fear would make both animals release. Otherwise, predators would be in luck. The female assistants were sceptical.

So the next time I came across the situation, which happened rather often since humans are so alarmed and repelled by the sight that they want it removed IMMEDIATELY, I tried scaring the two dogs. Either I wasn’t very scary or the female assistants were right. After that, I made sure that I was very late to the call so I could just pick up two separate animals, assuming they were still around.

I called Animal Control where Burgwin said, “The county will pay for basic emergency care but then you must bring it here to the shelter. The county will not pay for extensive care and if you authorize it, you will pay for it yourself.” This was the proper answer but not the moral or emotional one. Burgwin was relentless about turning an officer’s decisions back to the officer. With authority goes responsibility and decision-making, full on with consequences. The same as for military or for civilian police or -- come to look at it -- for doctors and veterinarians.

The dog was wearing a nice red harness with many tags attached. I called again, this time to find out the owner of the dog according to the most recent license. The owner didn’t answer the phone. I went back to the table where the dog had not stirred. The veterinarian had inserted an IV. We faced each other again. “I’m just keeping the animal alive while you decide what you’re going to do,” he said. “I can NOT afford to pay for every injured animal that comes in here!”

“But this is obviously a valued pet. We know who the owner is -- this is not an anonymous stray.”

His anger level went up. “People abandon their dear pets as soon as there’s a bill attached.” I suspect his practice was not doing well. Maybe his bedside manner.

I’d just moved to an apartment of my own and paid deposits and so on. Money was tight. Maybe he was right about the owner not appreciating his dog coming to the vet. None of my family ever took pets to the vet.

“Of course, what does animal control care? You people are so callous from killing hundreds of pets that you can hardly be expected to do anything. I’m surprised you brought this dog in here.”

I couldn’t hold out any longer. I slapped down my VISA. Then I left the dog there, now a private dog instead of an impound, and went to the address of the owner which proved to be a neat little brick house. I left a long note attached to the screen door. That evening, back at the shelter, the owner called with grateful thanks. The dog was still alive. She was paying the bill happily.

Burgwin didn’t criticize me for my decision. It was mine and I was lucky. He was happy for me that I was lucky.

Months later, in winter, I responded to an injured dog call that said a police officer was waiting. The dog was a black lab whose leg had been mangled by a car with studded tires. The officer had put the dog in the trunk of his squad car and stood by with the lid lifted, watching for me while guarding the dog from further injury. I thanked him -- he was almost in tears for the dog’s sake. The dog was stoic and grateful.

This time I had a developed friendship with Dr. Plamondon, founder of DOGS (Drinkers of Good Scotch) and one of the best veterinarians in town, much less my area, and since this was a good dog, wearing tags, I took the poor fellow to Dr. P. He didn’t ask any questions, just got to work sorting and sewing.

Dr. P. was a bit of a philosopher. We talked once about the appeal of animals and I compared cows to deer, with cows on the losing end. Dr. P. drew himself up and delivered an eloquent defense of the seductive beauty of the Brown Swiss Dairy Cow, entirely persuasive.

Once he told a very funny story at his own expense, about being in training with a prominent veterinarian when a customer rushed in the door early one morning and said, “Here’s my dog! Be sure you have him fixed by 5PM and I’ll pick him up after work.”

He was a very good dog, show quality, and Dr. P. wondered why the owner wanted him neutered, but he assumed the customer was always right and there must be circumstances he didn’t know, so he set to work right away. The dog would have the rest of the day to recover for the trip home.

But when the customer came back, he said, “Wait! His ears look just the same! Why didn’t you fix them?” He wanted them surgically altered to stick up, as is the custom with some breeds. (In England they don’t do that sort of thing anymore except to dock tails and dewclaws that would get torn or loaded with burrs in field dogs.) He was not happy to discover that a lot of stud fees had been surgically removed.

Dr. P. was a big man with hands to match, so somehow it was a little surprising -- but very endearing -- that his specialty was birds. One room was full of recycled premature baby isolettes for the recovery of exotic birds. I heard talk in there, stuck my head in, and saw macaws and parrots, all swearing and declaring and sometimes even singing bits of human songs. On another occasion I stuck my head in another door and discovered a springer spaniel joyfully having water therapy for his back in a bathtub full of hot water. His therapist was a rubber ducky.

It was wonderful to me, a happy privilege of my role, to be able to go in the back door of this veterinarian, as though I were part of the team. While Dr. P. worked on the black lab, I called the shelter to get the owner’s name and then called the owner. The owner said, “That dog is constantly getting into trouble and I’m tired of bailing him out. He can just take care of himself. I’m not paying any inflated bill from a tinhorn veterinarian. The dog can pay for himself. Maybe that will teach him.”

Dr. P.’s reaction was a bitter laugh. I drove over to the owner’s house and wrote him a ticket. He went to court to argue about it. I told the judge what had happened. He was ordered by the judge to pay the veterinarian bill as well as the highest fine possible. He didn’t get his dog back.

There was one veterinarian I learned to avoid -- all we female officers learned to avoid him -- because he always thought the animal should be “checked for ringworm” by carrying it into a small dark closet so he could shine an ultraviolet light on it and “accidentally” bump into the female officer’s front. Another was a crook who would put down foreign objects under the animal while taking an x-ray and claim that surgery was necessary to remove it. One of the services we provided to veterinarians was the removal of animals who had died or been euthanized, which was okay, but one veterinarian specialized in euthanizing slow greyhounds and sometimes there were a dozen of them, so many that there was no room for the live dogs in the truck. Burgwin ended that.

One of the veterinarians I enjoyed most -- maybe for the wrong reasons -- was an older divorced man who styled himself a feminist, and stocked “MS.” magazine in his waiting room. His staff seemed to be entirely pretty women under thirty, but that’s not unusual in a veterinary practice. Animals tend to attract “mommies.” (These days the women just go ahead and become veterinarians themselves.) Anyway, since he seemed open to sort of racy topics, I asked him a question for which I really wanted an answer.

Dogs in the throes of coition get stuck together -- “tied” in the jargon -- and I wanted to know how that happened. (For many observant young boys it’s a source of great worry -- until they find something worse when they run into the myths of the “vagina dentata” which bites off whatever is inserted, a myth so widespread that the Blackfeet have a story about Napi introducing a stone as a surrogate so as to break off all the teeth and make his partner a lot safer for him and his beloved parts.)

More important, I wanted to know how to get two dogs unstuck quickly so as to avoid the repeated debacle of the female running off, dragging her friend by a most inconvenient and painful appendage. Did throwing cold water on them really work? And whose fault was it anyway? Did the male swell up or did the female lock on?

A half-hour of diagrams and argument later, I was no wiser. It seems that the female dog has a sphincter just a bit inside the vagina entrance and this grabs during intercourse. But the male dog has a ring of flesh on his penis that swells up during intercourse. Both animals need to relax for these swellings and constrictions to ease. They are meant to stand there “tied” for a while to give the sperm some swimming travel time, which helps especially with dogs because there might be a serious size differential, unlike wolves or coyotes. The vet’s position was that fear would make both animals release. Otherwise, predators would be in luck. The female assistants were sceptical.

So the next time I came across the situation, which happened rather often since humans are so alarmed and repelled by the sight that they want it removed IMMEDIATELY, I tried scaring the two dogs. Either I wasn’t very scary or the female assistants were right. After that, I made sure that I was very late to the call so I could just pick up two separate animals, assuming they were still around.

Friday, August 25, 2006

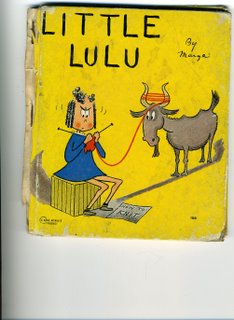

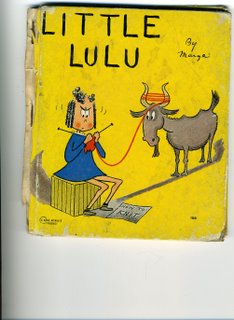

Little Lulu Is Arrogant

Little Lulu thinks she knows everything!

My finished book “Twelve Blackfeet Stories” arrived via UPS yesterday. I opened it and had a good laugh. The directions had said, “Be sure you proof your manuscript and cover one last time, even if you think you’ve done a perfect job.” Well, I thought, I’ve been over this stuff a million times! I can’t have missed anything!

So what’s right there on the cover? I forgot to hit the button that removes the “secret symbols” like the bent arrow that means “start a new paragraph.” And in the time-line at the end of the stories, I failed to capitalize the sub-heading on the story about “Cutnose Woman.” It’s arrogance, pure arrogance.

Little Lulu is like Napi -- she rushes in, thinking she knows all the answers. She should have asked someone to “edit” for her.

Luckily, Lulu.com provides for revisions. In fact, it has a little counter to keep track of how many there have been! So this time I will wait overnight until I can really find the errors -- or at last the main ones -- and correct them.

Other than that, the book looks pretty good and I will go ahead and pay the $100 so it will be listed on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Google. That take months, so it should be there in time for Christmas. One of the main things about this publishing stuff is the immense lead times, which I’m gradually beginning to understand!

Little Lulu just can't wait!

Wednesday, August 23, 2006

The Ministerial Mug Shot

I kinda wanted to add a mug shot to this blog sidebar, which means I have to post it, so I thought I'd write about it, too, for those who care.

We thought I should have one flattering photo for the Unitarian Universalist Montana Ministry (UUMM...) as distinguished from Montana Ministry of the Unitarian Universalists, which would be MMUU. Actually, I kind of liked the MMUU idea in a home-on-the-range sort of way. All the newspapers in our four towns (Bozeman, Great Falls, Helena, Missoula -- alphabetical order) used this same little photo over and over. That was 1982-85. The session cost $60 and more photos cost $25. I thought about trying to buy the negative for a while, but now scanners make that a moot point.

The photographer was a guy named William R. Sallaz, whom I see from Google is now in Fort Collins but was then in Helena. His instructions were to make me seem "accessible, intelligent, and rather humorous." See what you think. I told him I'd be back for another photo when I lost some weight -- but I didn't lose weight, I lost hair. Now I'm almost back DOWN to that weight in the photo. The glasses have gone out of fashion. Otherwise, you could probably recognize me from this.

TWO HUGE STATUES IN BABB, MONTANA

When I told Ray Djuff, author of many books about Glacier Park or rather Waterton Peace Park since he comes from the Canadian side, that I had a better library on the Blackfeet than some public libraries, he called my bluff by arriving to spend a couple of days at my work table going through what I had. As a sort of “hostess gift,” he sent me these photos he had taken of the Scriver sculptures now emplaced at the public schools in Babb.

These are fiberglass monuments that were in front of the Scriver Museum of Montana Wildlife and Hall of Bronze in Browning. When the Montana Historical Society arrived to take away all of Bob’s work, they were hard-pressed to know how to transport these monster statues or where to put them if they got them safely to Helena, so they loaned them to the Blackfeet Tribe. The Tribe has a lot of empty warehouse space up at the Industrial Park by the railroad depot, so they stashed them in there to save them from vandals. There is still enough animosity against Bob for renegades to feel justified in spray-painting or otherwise defacing his works. (Of course, there was a great outcry of protest when the statues were missing!)

In fact, the rumor went around that the big bull-rider statue was dropped at some point and was “busted.” However, Gordon Monroe was on the tribal council at that point and he was the person who had made the casting from the original mold in the first place, so he was perfectly capable of fixing it. Gordon has done all of Bob Scriver’s fiberglass casting as well as creating some major works of his own. For instance, his huge “corpus” of Jesus on the Cross is in the Church of the Little Flower in Browning.

These two huge works come out of the rodeo phase of Scriver’s work, which is all some people really think of when they reflect on his entire body of a thousand sculptures, partly because the rodeo sculptures are what he always sent to the Cowboy Artists of America shows. “An Honest Try,” which is a portrait of Bill Cochran on a Reg Kessler bull, became Bob’s trademark and motto, replacing the “Lone Cowboy” motif he used earlier. This one-and-a-half life-sized version was commissioned for the Inland Trade building in Kansas City in 1986.

The other big statue is a version of the PRCA (Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association) figure on their official belt buckle. A bronze version of it is behind the Montana Historical Society building in Helena. They gave Bob one of these buckles and he may have been buried wearing it.

The tribe didn’t mess around with deliberations over where to put these statues. They just did it. The Montana Historical Society didn’t know until I told Arnold Olsen and I didn’t know until I was Googling School District #9 and came across the pictures on their website. I still haven’t seen them in person.

Bob had many connections to Babb, mostly from the days when he lived all summer in a cabin he’d built halfway between Babb and St. Mary. I had connections there myself, partly through some of the Blackfeet Sandwich Shop and Free School faculty who later taught at that school and probably had something to do with this, and partly through the year I was the Methodist minister for the Blackfeet Reservation and preached in Babb every Sunday. Because the St. Mary Valley opens to Canada rather than the reservation, the culture is a little different there. It’s more of a tourist town with white businesses that have been there since homesteader days, gradually becoming Indian businesses as the generations intermarry -- but with a strong strain of Metis.

Anyway, they look great in front of the new Babb school and I hope they have a long and happy life there.

Tuesday, August 22, 2006

LAND OF THE BURNT THIGH by Edith Eudora Kohl

Many thanks to Genevieve (Prairiebluestem.blogspot.com) for tipping me off about “Land of the Burnt Thigh” by Edith Eudora Kohl, published by the Minnesota Historical Society Press in 1986 after an original publication by Funk & Wagnalls in 1938. (ISBN 0-87351-199-9) I got my copy via the Internet for only a dollar and a half, plus postage, because it had underlining. Luckily I would have underlined the same things. This is one of the best homesteading books yet.

The reason Genevieve mentioned it is that the happenings took place about an hour’s drive south and west of Faulkton, South Dakota, where my grandparents homesteaded on adjoining land and started their family in the two-room tarpaper shack created by dragging their two claim shacks together. I grew up hearing stories like these. They were THERE.

This particular version is about two young sisters, not particularly robust, who got the notion of going out to the West and starting new lives. As is the pattern, it was much different and much harder than they ever expected. For one thing, the land had just been removed from Sioux lands but the Indians were still pretty much there. Not hostile, just there. For another, there were always either too many people or not enough people -- great surges and ebbings of population. And they really had not grasped what a claim shanty was like. To say it was minimal was to give it more credit than it deserved.

By happenstance, one sister became the local schoolteacher -- though it was necessary to hitch up a team and drag her shanty to the other side of her claim so she’d be able to walk over to the school house. The sister who is the author then fell into being a newspaper woman of sorts. A local publisher was necessary to monitor the claims for legal purposes and had to reliably print highly technical data. An alert man had established a string of news-posts, each with old faulty presses and determined women. Since the schoolhouse and newspaper were there, somehow a post office and store grew out of them. Pretty soon they had a town called “Ammons.” It’s not on the map now.

Eerily enough, in about 1910 Bob’s dad bought his house in Browning from a man named Ammons and the same trader originally built the warehouse which Bob tore down and rebuilt into the Museum of Montana Wildlife, now the Blackfeet Heritage Center. The “town” of Ammons eventually burned to the ground due to a stove fire, leaving the girls with only the rags on their backs. (The reason the Brule is called “the Land of the Burnt Thigh” is that some young Sioux men were caught in a prairie fire and escaped by wrapping themselves in their buffalo robes, except that their bare thighs were burned on the hot ground.)

The same dramatic events -- land rushes, blizzards, prairie fires -- as in all the other versions of homesteader stories are told new somehow this time. I think it is because Kohl adds a subtle political dimension that most other writers weren’t even aware of. What she saw was that this taking of land from the Indians and then populating it with desperate, determined, impoverished people, made a lot of merchants back east very rich indeed. Not to mention the railroads. The Roaring Twenties were the direct result of the exploitation of the prairies in the two previous decades. She doesn’t pound on this, but it is very clear. Of course, she is writing in the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl that resulted.

Beyond that, she tells of the prairie political heroes who rose to defend the little struggling people and their communities, and of how they all learned to cooperate in order to help each other, eventually leading to today’s farm co-ops. She recognizes that the small struggles of her rickety printing press (She got so mad at it one day that she pounded it into pieces and threw it out the door!), became a voice in the land strong enough to lead towards progress and hope. (She marched off to the owner of the news-post and demanded a new press!)

Kohl is just a darn good writer with an eye for the telling detail and a knack for describing character, whether it is in a horse or a person. Cowboys like Coyote Cal ride in and out of the lives of the homesteaders -- constantly grieving and angry about the closing of the open range and yet helpful to the very people who were doing it. Some of the older characters turn out to have more staying power and inner resources than the youngsters. And the youngsters are amazingly resilient and self-reliant specimens. The sisters become involved in the Indian lives and eventually had to deal with the shrewd and solemn leaders, whom they MUCH respected.

Both sisters get hooked on the prairies. I can relate. In spite of disasters and sieges of illness and near-starvation or maybe death by thirst or -- worst of all -- an invasion of little brown worms by the zillions who swarmed over them even in their sleep, in the end they don’t want to go back east. One marries and stays -- the other heads West.

Valier is three or four generations away from these pioneers. They haven’t forgotten. Many of their characteristics are very much the same. Sometimes that doesn’t work very well in modern times. Some of their children could sure use a little hardship. The local newspaper follows rather than leading. Some say that as many as half or two-thirds of the original homesteaders left, but these are the people who stayed.

The reason Genevieve mentioned it is that the happenings took place about an hour’s drive south and west of Faulkton, South Dakota, where my grandparents homesteaded on adjoining land and started their family in the two-room tarpaper shack created by dragging their two claim shacks together. I grew up hearing stories like these. They were THERE.

This particular version is about two young sisters, not particularly robust, who got the notion of going out to the West and starting new lives. As is the pattern, it was much different and much harder than they ever expected. For one thing, the land had just been removed from Sioux lands but the Indians were still pretty much there. Not hostile, just there. For another, there were always either too many people or not enough people -- great surges and ebbings of population. And they really had not grasped what a claim shanty was like. To say it was minimal was to give it more credit than it deserved.

By happenstance, one sister became the local schoolteacher -- though it was necessary to hitch up a team and drag her shanty to the other side of her claim so she’d be able to walk over to the school house. The sister who is the author then fell into being a newspaper woman of sorts. A local publisher was necessary to monitor the claims for legal purposes and had to reliably print highly technical data. An alert man had established a string of news-posts, each with old faulty presses and determined women. Since the schoolhouse and newspaper were there, somehow a post office and store grew out of them. Pretty soon they had a town called “Ammons.” It’s not on the map now.

Eerily enough, in about 1910 Bob’s dad bought his house in Browning from a man named Ammons and the same trader originally built the warehouse which Bob tore down and rebuilt into the Museum of Montana Wildlife, now the Blackfeet Heritage Center. The “town” of Ammons eventually burned to the ground due to a stove fire, leaving the girls with only the rags on their backs. (The reason the Brule is called “the Land of the Burnt Thigh” is that some young Sioux men were caught in a prairie fire and escaped by wrapping themselves in their buffalo robes, except that their bare thighs were burned on the hot ground.)

The same dramatic events -- land rushes, blizzards, prairie fires -- as in all the other versions of homesteader stories are told new somehow this time. I think it is because Kohl adds a subtle political dimension that most other writers weren’t even aware of. What she saw was that this taking of land from the Indians and then populating it with desperate, determined, impoverished people, made a lot of merchants back east very rich indeed. Not to mention the railroads. The Roaring Twenties were the direct result of the exploitation of the prairies in the two previous decades. She doesn’t pound on this, but it is very clear. Of course, she is writing in the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl that resulted.

Beyond that, she tells of the prairie political heroes who rose to defend the little struggling people and their communities, and of how they all learned to cooperate in order to help each other, eventually leading to today’s farm co-ops. She recognizes that the small struggles of her rickety printing press (She got so mad at it one day that she pounded it into pieces and threw it out the door!), became a voice in the land strong enough to lead towards progress and hope. (She marched off to the owner of the news-post and demanded a new press!)

Kohl is just a darn good writer with an eye for the telling detail and a knack for describing character, whether it is in a horse or a person. Cowboys like Coyote Cal ride in and out of the lives of the homesteaders -- constantly grieving and angry about the closing of the open range and yet helpful to the very people who were doing it. Some of the older characters turn out to have more staying power and inner resources than the youngsters. And the youngsters are amazingly resilient and self-reliant specimens. The sisters become involved in the Indian lives and eventually had to deal with the shrewd and solemn leaders, whom they MUCH respected.

Both sisters get hooked on the prairies. I can relate. In spite of disasters and sieges of illness and near-starvation or maybe death by thirst or -- worst of all -- an invasion of little brown worms by the zillions who swarmed over them even in their sleep, in the end they don’t want to go back east. One marries and stays -- the other heads West.

Valier is three or four generations away from these pioneers. They haven’t forgotten. Many of their characteristics are very much the same. Sometimes that doesn’t work very well in modern times. Some of their children could sure use a little hardship. The local newspaper follows rather than leading. Some say that as many as half or two-thirds of the original homesteaders left, but these are the people who stayed.

Saturday, August 19, 2006

Little Lulu Makes Peace

AWRIGHT!! I uploaded "TWELVE BLACKFEET STORIES" on August 14. (Bob Scriver's birthday -- he would have been 92.) A handful of flyers at the Piegan Institute "War and Peace" conference and a mention on popular blog, and I've already made $14 in royalties! Can fame and fortune be far behind?

Who cares? I'm having a great time!

Prairie Mary (AKA Little Lulu)

[No, I did not draw these cartoons. Credit goes to a person named "Marge." I don't know much about her except that she was popular in the early 20th century.)

INNAIHTSIIYI: Examining Blackfeet Concepts of Peace (and War)

I have a video tape on which Bob Morgan, fine Helena artist, says that Charlie Russell loved Indians because he loved their “gentle ways,” their small household graces and courtesies. It’s not a side often explored, but today at Piegan Institute we were treated to a demonstration of “Innaihtasiiyi” during “An Examination of Peace (and War.)”

The Cuts Wood School building itself is a pleasure to enter with its high ceilinged light-well and many-doored meeting room standing open to the yard. Rosalyn LaPier and Shirlee Crowshoe had taken many small measures, like providing each of us with a sachet of sweet pine tied up in calico wth a ribbon. The room was scented with it and when I got home, I smelled of it: richer and deeper than sweetgrass. Lunch was buffalo cooked traditionally with potatoes, onions, and cactus. “Where did you find the cactus?” I asked.

“Grocery store,” tossed off Rosalyn, who is always resourceful in the most literal sense. It was green strips, like very mild green pepper. “Didn’t have time to dig prairie turnips,” she said. But there was time for berry-picking -- a good berry year -- and we all had “sarvisberry” pie. (Except for the Canadians who had “saskatoon berry” pie. Same berry. One of the better things about this conference is that draws from both sides of the 49th parallel, even now when it can be a bit tricky to cross.) This topic of “peace” is relevant in the extreme at the moment. Even Canadians have troops in the Middle East.

Theodore Binnema, U of Northern British Columbia, is the author of “Common and Contested Lands.” (Check it out on Amazon, which now offers a glimpse inside the book, a concordance, and an evaluation of how hard to read the book is -- amazing! Um, about 75% of books are easier to read than Ted's book. But are they worth it?)

Ted’s formal topic was “The Significance of Peace and Warfare in the 18th and 19th Centuries among the Blackfoot.” His next book will be a tighter focus on the same material that he developed earlier. He says his overarching interest is how societies interact with each other and the way that individuals and families interact with each other, and then the ways that those two levels influence each other. (At least 25% of readers of this blog should still be with me.)

Ted identifies two schools of thought among people who work with this material: one is romantic and claims that what happens (for instance on the high prairie) is because those people in that place and time are essentially unique. The Plains Indian wars will never be replicated. The possibly unconscious assumption in this group is often that the most colorful and appealing explanation of what happened is the one likely to be true.

The other point of view is more practical and assumes that humans in different times and places often share characteristics that make their study useful for the management of our own lives. How do we create stable, peaceful societies? What are the social structures that encourage good behavior for the whole society? (Think marriage, rule of law, the protection of marginal individuals, networking groups, religious beliefs.) Ted says he belongs to the latter group. (I myself come down squarely on both sides: the first as a writer and the second as a citizen.) He did not address religion and neither did anyone else. Probably a wise omission.

Ted gave some attention to Peter Fidler, who is little known on the US side but very much on the minds of Canadians. He was essentially the first white man into the area. (Part of his journal is on display at “Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump.”) Ted’s point was how educated this man was -- he subscribed to “Monthly Review” which probably came to him as a stack of the year’s issues on the one supply ship that arrived annually, and through that source was often aware of new developments in science and so on before the European world as a whole really registered them. He was one of the first to realize that vaccination against smallpox was proven possible. Fidler and other early fur traders NEVER used the word “savage,” and often spoke of Indians as “civilized.” He recognized the complexity and effectiveness of arrangements among the people of each tribal group and among the larger alliances.

Some people assert that “aggression” in a society is the product of genes (right now genes are supposed to explain everything) and will say that Blackfeet, Maori and Prussians are genetic warriors. They will neglect the cultural shaping of diplomacy, strategic marriage or trade alliances. Also, they will not think about the huge expense of warfare in terms of material loss, loss of time normally devoted to hunting/gathering/making, and loss of life, which are always deterrents. (Unless one belongs to a class shielded from the losses -- think this isn’t relevant to the front page of our newspapers?)

On the other hand, defensive warfare to protect turf and resources (then, bison -- now, oil) is sometimes inevitable. At this point, the principles are available to analyze what Darrell Kipp calls the “population hydraulics of the plains.” That is, a strong tribe tries to move in on the resources of a weaker group, or a weak group makes an alliance with a strong group by offering them territory or a new skill, or two groups who have taken many losses agree to stop fighting. Peace cannot happen without BOTH parties wanting it. One cannot force peace.

Much of the early defensive warfare was like the “bluff charging” of a grizzly bear. A display, an advance, then a withdrawal before any damage to the aggressor. This may make a smaller, weaker group back off. The advent of horses and guns destabilized the relationships among the tribes by making attacks so much more deadly, speedy and distant. (Like bombing from the air, or missiles.) Also, because these new factors as well as other trader-supported resources (whiskey, canvas, metal objects) created inequities between groups, they encouraged jealousy, greed, hatred and other aggression-feeding factors.

Ted said that as nearly he could tell, there is NO mention of “counting coup” in the historical literature. Worth an expedition into the libraries by some motivated young scholar! BUT it was clear that older men who had “been there, done that” were not very enthusiastic about war, while the young men who still had to establish their “street creds” were not about to give up war until they’d had a chance to fight. Once the war is on, community support rises in proportion to the risk. Ted mused that Canadians never had “veteran” car license plates and only a percentage of US states provided them, until this last few years of Middle East conflagration. Now EVERY province and state offers Vet plates. Being a warrior is again a source of prestige.

Bands that were on the frontiers were LESS willing to war, since they were on the front lines and more likely to know more about the “out groups,” even to be intermarried with them or trading partners. Groups far separated were less likely to be enemies than those nearby. The flooding of white people onto the plains destabilized the existing arrangements, throwing some into war while forcing an unwanted peace on others. Such massive change always escalates mortality if only through loss of economic stability. Starvation and disease go hand-in-hand with war.

So were the Blackfeet more warlike than any other tribes? Only because they were backed up against the mountains with the last of the resources, under siege from many others desperate to survive. They used their horses and guns effectively.

Hugh Dempsey, Chief Curator Emeritus, Glenbow Museum, is one of the premier historians of the Blackfoot Confederacy and has written many books. He discussed treaties of various kinds in considerable detail as to times, places and parties involved in ways too intricate for me to write them down. (These talks were videotaped and ought to be available from Piegan Institute later.)

Basically, he explained that treaties were of many different kinds and often quite utilitarian. A tribe would ask for safe passage to trade at a fort on another tribe’s territory or for a summer’s amnesty in order to hunt buffalo. The Kutenai, for instance, would come over the mountains to hunt and be granted that privilege. A man from the Kutenai tribe might approach by stealth in the night, sit on a ridge overlooking the camp, and wait to be discovered. If the Blackfoot tribe was willing to deal, someone would ride up and escort him down to the chief’s lodge for tobacco and talk. Occasionally a woman might be sent or volunteer to come.

(In modern times and in rural areas, this is still a good strategy. One drives into the ranch yard, waits in the car for a while, maybe honks briefly. If anyone wants to talk, they will come out to the car. This is particularly wise in a yard guarded by dogs. Danger apart, it’s a courtesy when people are so isolated that they might not be wearing appropriate -- or any -- attire!)

Fur traders who wished to exchange commodities for skins might be the initiators of peace treaties, so as to increase their clientele. They would be motivated to get the goodwill of the prominent and powerful in surrounding groups and might be willing to use marriage for this goal. (For instance, Culbertson benefited hugely from his marriage to Natawista, both from good will and from her skills in diplomacy, and they were often able to bring peace.)

But blunders were possible. A Kutenai man, who came over to hunt buffalo under an agreement with the Bloods, wandered off and stole a horse from the Piegan, which were a related but separate band not involved in the arrangement. When he came back to his own hunting group, he was spotted by Bloods who thought he had stolen the horse from them, a violation. They attacked the camp and killed many. As a marker of this event, Kutenai returned to pile rocks in an effigy of the dead perpetrator. It might be still there, near Waterton Peace Park. The original name of the Marias River was “the River Where We Killed the Kutenai.”

But some individuals became known as “peacemakers;” in fact, one whole family is called “Peacemaker.” In particular, one chief who was at least influenced by Methodists, if not converted, changed the argument for peace from simple advantage to the desire to avoid harm and suffering to people. This argument is present now in world rhetoric, but still shares ground with those who are peaceful only when it is expedient. (We still need Amnesty International.)

James Dempsey, son of Hugh Dempsey and also a Ph.D. level historian at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, gave a talk with overhead illustrations from his impending book, “Warriors of the King: Blackfeet War Art.” His wonderful material was histories painted on robes or on cotton canvas banners. He was able to interpret these and connect them to the historical records of battles, surrenders, and relationships. He remarked that one of the important tropes for war was gambling, a continuing preoccupation for Native Americans (as well as many others), which meant a high awareness of risk but a willingness to plunge onward no matter what the cost because of the possible rewards. This can be empowering.