May Sarton in old age

For a long time I maintained a shelf of May Sarton books, beginning with “Journal of a Solitude” and then trying to keep up with the dozens and dozens of books she wrote. Eventually, maybe after “Anger,” I parted company and sold the books. I had intended to read “Faithful Are the Wounds,” but then sort of forgot it. Now Peter Matthiessen’s death has propelled me back through it. The book is transparently about Peter’s uncle, F.O. Matthiessen, who committed suicide in 1950. But only about one aspect of the older Matthiessen, who was a close friend of Sarton’s -- the political side. Still, she is tracing how that impulse comes out of the puzzle of family.

Like Peter, F.O. was a “Yalie,” but hardly a Bush-type. “In 1923 Matthiessen graduated from Yale University where he was managing editor of the Yale Daily News, editor of the Yale Literary Magazine, and a member of Skull and Bones. As the recipient of the university's Deforest Prize, Matthiessen titled his oration, Servants of the Devil, in which he proclaimed Yale's administration to be an "autocracy, ruled by a Corporation out of touch with college life and allied with big business".” His teaching career was at Harvard.

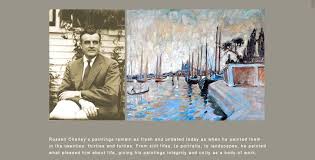

Russell Cheney and one of his paintings.

His lover was a painter, Russell Cheney, twenty years older than he, who died five years before “Mattie’s” suicide. They were what might be called “diplomatically gay.” That is, the general public was unaware but the friendship circle just accepted it. Sarton does not address this unless it’s too disguised for an outsider to know, maybe by switching genders. There are no painters in the story. On the other hand, the book is very much structured by dyad relationships, mostly brilliant men with supporting wives, with a fierce old spinster as a main character, presumably the clearest avatar of the author herself.

The book was published in 1955, when professors were still brilliant, some of them still hoped Communism would not turn out to be monstrous so the Left could stay unified, and those Lefty men faced the Inquisition of McCarthyism, which did pursue F.O. Matthiessen. This is the core plot line as the protagonist, Edward Cavan, struggles with his perhaps overly strong conscience and the demands to be bamboo rather than oak. In the end he will not bend. So falls.

May Sarton

As one expects from May Sarton, this is elegant, measured writing -- a little old-fashioned, but it suits the theme in that particular time and place. She could call up the State House’s golden dome restoration glowing against all the red brick of Beacon Street without Unitarians feeling the wound of moving out of Number 25 next door. In those days professors argued hard about lofty ideals and endlessly smoked nicotine cigarettes. Faculty dynamics were as cut throat as they are now. Students were remarkably innocent of anything but pretensions. Conversations take place in cafes, not naked in bed. No one in this book eats pizza.

The State House on Beacon Street

The title comes from Proverbs 27:6, King James Version “Faithful are the wounds of a friend; but the kisses of an enemy are deceitful.” Mostly these friends were constantly insulting each other even as they struggled to understand and help. I didn’t recognize any kisses from enemies. The book is in two halves: the incidents leading up to the suicide -- which was by throwing himself under a train, thus cutting himself in half. (F.O. jumped from a height.) Then finally the reaction from friends and family before a description of the attack on his character by a Senate inquiry, not because of the suicide but because of his political leanings.

Sarton’s trademark descriptions of settings of beauty are always there. Now that I’ve looked for Russell Cheney’s paintings, I see the echo of images. (He is CLEARLY nothing like Dick Cheney.) It’s worthwhile to google to see the paintings just for the pleasure, but it has nothing to do with the plot. http://www.russellcheney.com/hp.html

by Russell Cheney

In fortunate corners there are still traces of what Harvard and other Ivory Towers once were, but even that is eroded now by the tumult of the last half of the twentieth century. In those days no one imagined that feminists could depose the president of Harvard. Maybe the old dynamic of privileged prestige continues in BBC series like “Morse” and “Campion.” But as Japan knows very well, what cannot be captured by violence and defiance can simply be purchased if one waits for the right moment.

A dyad type closer to power inequity is pointed out: that between industrialist achievers as steel-cold fathers who send their sons to university for status purposes but then appear cruelly destructive according to the abstract principles of their estranged sons. This is not examined closely. Still, it’s interesting that one of Peter M’s life-dilemmas was his in-house war with his father, who was the brother of F.O. Matthiessen. “Edward Cavan,” F.O.’s stand-in, has this same shadow. In fact, it’s a theme of the century, a tragic one as men make themselves inhuman for the sake of sons who find them exactly that. It feeds back into the dilemma of marriages based on gender assignment: the strong, rational, achieving men and the warm, beautiful, elegant women. Wallace Stegner is eloquent on the subject. It can be a science vs. humanities conflict.

In the book the sister of “Edward” has married a man named Lucier and F.O.’s real sister was named Lucy. She is portrayed as conventional, prosperous, the wife of a California surgeon, estranged from her brother, trying to understand but not succeeding. I don’t know how factual that was. I gather that there has been considerable controversy about some portrayals among those who knew the principals in real life.

In terms of generations, this feels like what I just knew the very tail end of at the University of Chicago, and even then it was a little anachronistic since gays were out and the hippie years had trailed off. People were even a little like the Fifties, wanting to think in peace. But then came that wild wave of post-everything thought in the academy and an opposite rising tide of sentimentality and therapeutic cheerfulness elsewhere, both of them ignoring growing poverty and unable to prevent the “sand wars.”

So now we look around and see neglect everywhere -- from the decrepit bridges people are forced to live under, to financial arrangements that are out of control even for the one percent. The air and water are terrifyingly endangered. Food and meds may be poisoning us. It’s time to march all over again, but how do we do that without tearing ourselves apart like Edward Cavan or deluding ourselves as do so many others in this book? Is a life of sitting in a sheltered environment to read and write merely ineffective or might that finally be a source of salvation?

So now we look around and see neglect everywhere -- from the decrepit bridges people are forced to live under, to financial arrangements that are out of control even for the one percent. The air and water are terrifyingly endangered. Food and meds may be poisoning us. It’s time to march all over again, but how do we do that without tearing ourselves apart like Edward Cavan or deluding ourselves as do so many others in this book? Is a life of sitting in a sheltered environment to read and write merely ineffective or might that finally be a source of salvation?

May Sarton at home.

In one of the homages to Peter M. a young woman declared that she found reading “Wildlife in America” to be unbearable and only did it out of a sort of Calvinistic discipline. On what stack of mattresses does this terribly sensitive princess sleep at night? (I don’t care who with.) “Wildlife in America” was copyrighted in 1959, only four years after Sarton’s book. You can buy it on Amazon for a penny. Literally. What sort of novel could May Sarton make of all that? “Anger” isn’t strong enough. Try “Rage.” But then the princesses will simply flounce off in search of bling, pizza, and righteousness. They need seminars like those Edward Cavan was supposed to be teaching. Wounds teach one how to bear pain.

May Sarton as a young woman

No comments:

Post a Comment